In the last few posts of my blog I have been talking about the Museum’s holdings of hawkmoths, which amount to 289,000 specimens, and how the Lepidoptera section is dealing with the re-housing, care and accession of this important group.

This will be my last post related to this subject and in concluding I want to talk about a private collection of hawkmoths, specifically the Cadiou Collection, which has enriched and transformed the Museum lepidoptera holdings.

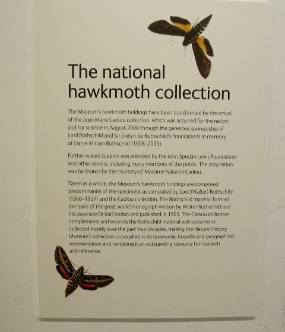

This large and valuable collection was purchased by the Natural History Museum in August 2008, thanks to the generous sponsorship of the Rothschild family, the de Rothschild family, the John Spedan Lewis foundation, Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust and members of the public.

The Cadiou Collection with its 230,000 specimens was acquired for the nation and for science in August 2008.

The Cadiou Collection with its 230,000 specimens was acquired for the nation and for science in August 2008.

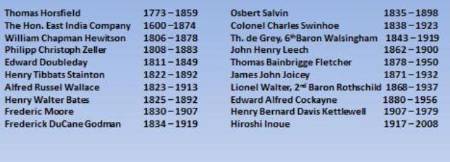

Dr Jean-Marie Cadiou was a non-professional lepidopterist with an interest in hawkmoths.

Cadiou began amassing his collection while working for IBM in California in the late 1960s, and continued during his subsequent employment with NATO and the EU Directorates General. At the time of his unexpected and untimely death in May 2007, he had authored or co-authored 32 scientific papers and one book, described 65 species and subspecies of hawkmoths and managed to create an extensive collection of thousands of specimens.

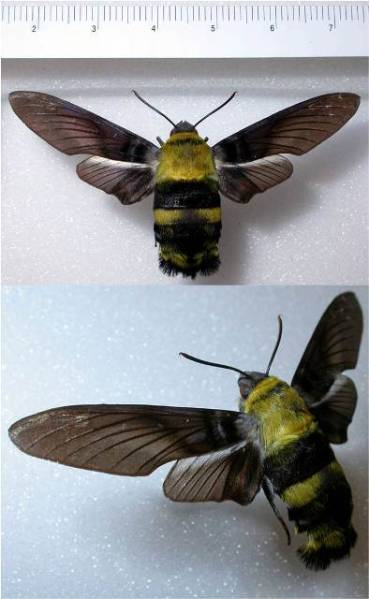

Four hawkmoths described by Cadiou. From top left clockwise: Eupanacra busiris ssp. myosotis (Sulawesi), Orecta venedictoffae (Ecuador), Xylophanes haxairei (French Guiana, Colombia, Ecuador, north Brazil) and Rhodoprasina corrigenda (Thailand).

Four hawkmoths described by Cadiou. From top left clockwise: Eupanacra busiris ssp. myosotis (Sulawesi), Orecta venedictoffae (Ecuador), Xylophanes haxairei (French Guiana, Colombia, Ecuador, north Brazil) and Rhodoprasina corrigenda (Thailand).

The Cadiou collection contained an estimated total of almost 230,000 pinned and papered specimens and when this collection was put on sale after Cadiou’s death the Museum couldn’t miss the chance to acquire it.

The reasons behind this interest were multiple:

- The majority of the Cadiou material was post-1970 with precise locality data.

- The collection contained at least one genus and 99 species and subspecies not represented in the Museum.

- It was also rich in species of which the Museum had only five specimens or fewer (at least 200).

In comparison the Sphingidae collections of the Museum at that time comprised 60,000 pinned specimens, many of which were over 100 years old.

Two colleagues of mine went to Belgium to pick up the collection in Cadiou’s house. The plentiful and various types of boxes containing the specimens had to be packed into large cardboard boxes for ease of transport.

Two colleagues of mine went to Belgium to pick up the collection in Cadiou’s house. The plentiful and various types of boxes containing the specimens had to be packed into large cardboard boxes for ease of transport.

430 cardboard boxes containing the collection were loaded into a hired large track for transport.

430 cardboard boxes containing the collection were loaded into a hired large track for transport.

Meanwhile back in the UK a large freezer was hired to quarantine the material before transferring it into the collection areas.

After 21 days in the freezer at -40°C, the boxes were finally moved in the collection area.

At that time the Lepidoptera collection was housed in one of the Museum's storage places in Wandsworth, while the new building that would have housed the entomology and part of the botany collections, namely the Darwin Centre, was being built in South Kensington.

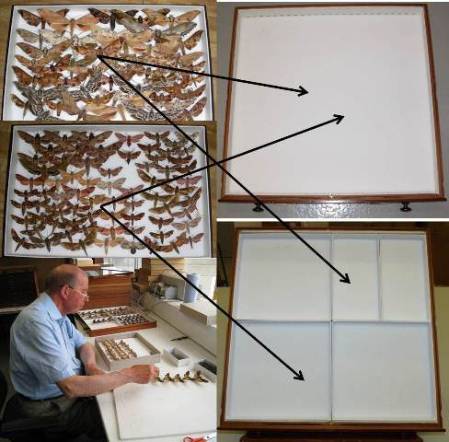

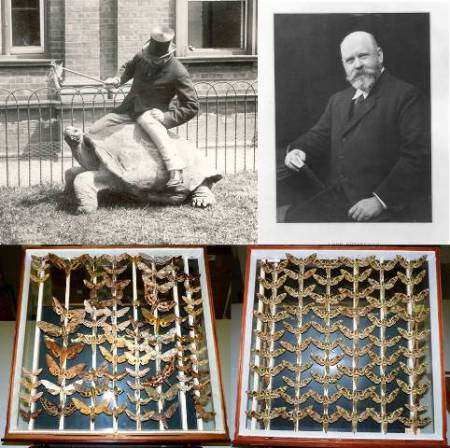

Once in the collection, we started the process of transferring the pinned specimens from various kind of boxes and drawers of the Cadiou collection into refurbished Rothschild drawers. Many curators and a volunteer were involved in the transferring of the material, and eventually, just before the Lepidoptera collection was ready to join the other entomology collections in the newly built Darwin Centre, in South Kensington, all pinned specimens from the Cadiou collections were transferred into Rothschild drawers and ready to be moved in their new home.

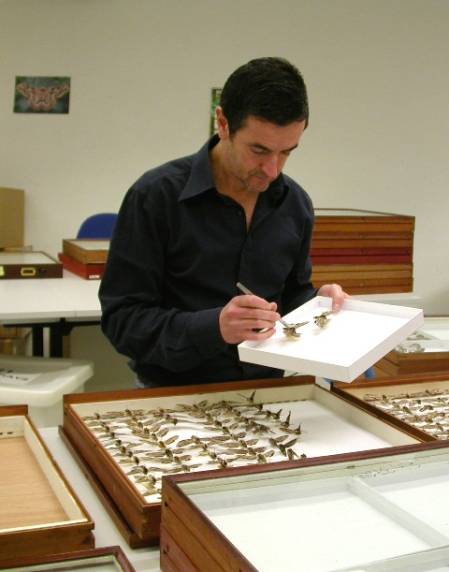

Our long-term volunteer John Owen transferring some hawkmoths from Cadiou’s boxes into Rothschild drawers.

At the end we had filled around 750 Rothschild drawers with pinned Sphingidae (top) and an extra 70 different types of drawers with non-sphingid Lepidoptera (bottom), all these from the Cadiou material.

We are now left with 120 boxes containing papered material, some of which has already been sent to Prague for mounting.

The actual amalgamation of all the Sphingidae in one large collection started in May 2010 and is still in progress. In this project I work alongside Ian Kitching, one of the researchers in our section and a world expert on Sphingidae. The aim of the project is to re-house the specimens from the main, supplementary, accession and the recently purchased Cadiou collections, into one collection inside refurbished Rothschild drawers.

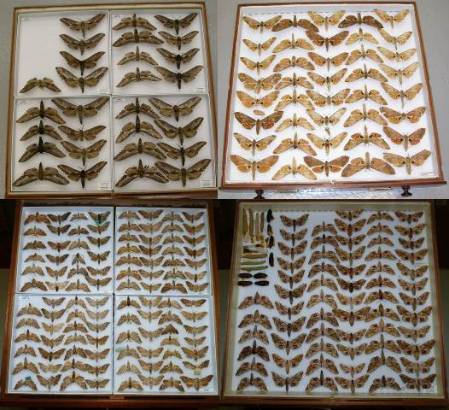

Some of the re-housed drawers of Sphingidae. From top left, clockwise: Langia zenzeroides ssp. formosana, Platysphinx stigmatica, Smerinthus ocellata ssp. atlanticus, Falcatula falcatus.

I am transferring the specimens using a relatively new way of arrangement which consists of rows of specimens facing each other. This method is particularly easy to carry out thanks to the falcate shapes of the dry pinned sphingids and has helped in increasing the number of specimens that fit in each drawer, therefore reducing the total number of drawers and ultimately the space necessary for their housing.

By February 2014 I created 877 Rothschild drawers of hawkmoths from merging main, supplementary, accession and Cadiou collections. A total of approximately 45,000 specimens have been transferred so far. These include 105 genera out of a total of 207. The re-housed taxa have all been labelled and had their location, with other important details, recorded in our electronic database.

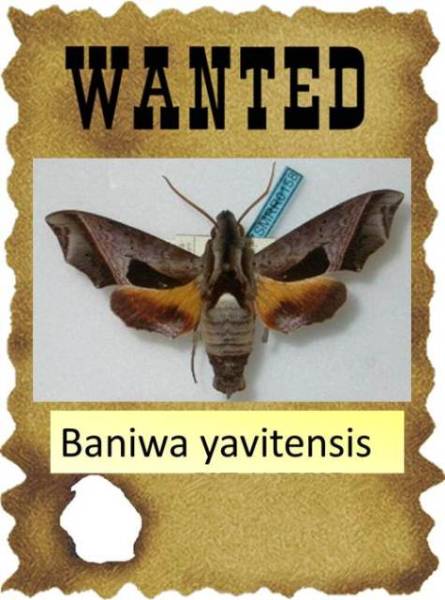

Allow me to make a plea, before concluding. Of the 207 genera of Sphingidae so far known 206 are represented in our collections. The only one currently missing is the genus Baniwa which has only one species described in it, Baniwa yavitensis, from Venezuela. We really would like to have one!

However, this is not an invitation to collect it from the wild as this species is very rare and almost certainly protected. We certainly don’t endorse indiscriminate and illegal collecting, and specimens entering our collections need to be accompanied by a regular collecting permit. So, if there are some collections out there with surplus specimens of Baniwa, keen on giving one away (I can hear someone laughing mockingly), please get in touch. We shall provide it with a comfortable, and most of all protected, accommodation.

That’s it! I shall now officially relieve you from any further information about sphingids…well, only for a while though, because as you may have noticed, I have a soft spot for hawkmoths and can’t resist conversing regularly about them.

Thanks very much for following this blog trend on hawkmoths; I shall keep you posted with more news on lepidopterans and the Museum’s collections.

One last thing, don’t forget to visit our Sensational Butterfly exhibit, which opens on 3 April 2014. There are also some moths in the house and who knows, you might be lucky enough to be brushed past by a skilful and hurried flyer…did someone just mention a hawkmoth.

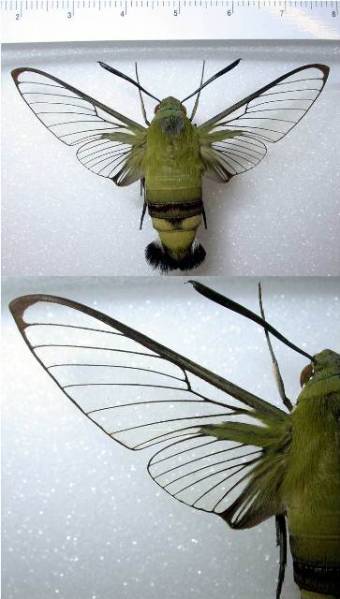

I photographed this beautiful Cephonodes hylas resting and feeding on the flowers of the a Scarlet Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) in a previous Butterfly Exhibit here at the Museum. Perhaps we'll be able to enjoy some nice hawkmoths this year too.

I photographed this beautiful Cephonodes hylas resting and feeding on the flowers of the a Scarlet Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) in a previous Butterfly Exhibit here at the Museum. Perhaps we'll be able to enjoy some nice hawkmoths this year too.