As some of you might be aware myself and colleagues are organising an upcoming symposium to celebrate 150 years since the birth of one of the great palaeontologists - Sir Arthur Smith Woodward. Smith Woodward might not be as well known as others but he did a lot for palaeontology, particularly fossil fish.

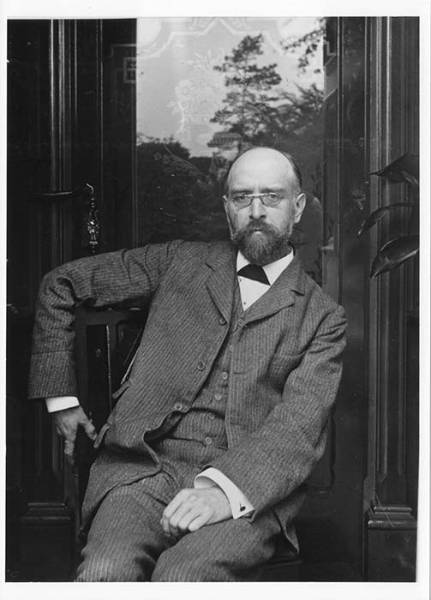

Sir Arthur Smith Woodward

Smith Woodward was born in Macclesfield on 23rd May1864. He started his long career at the NHM (then the British Museum - Natural History) when he was 18 years old in 1882 in the Geology Department. At this point the NHM had only been opened to the public for 16 months, so there was lots to do.

When he started at the Museum he quickly became involved in fossil exhibitions. Around the same time two large collections of newly acquired fossil fish specimens (containing thousands of specimens) previously belonging to two prolific collectors arrived at the Museum - Sir Philip Grey Egerton and William Willoughby Cole, (the 3rd Earl of Enniskillen). Smith Woodward realised how important these collections were and there were likely to be lots of new species and interesting specimens.

During his time Smith Woodward named over 300 different species of fossil fish and perhaps what he is best known for amongst fossil fish workers is a four part Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History) published between 1989 and 1901. This was and remains a very important reference for fossil fish workers. I often refer to the Catalogue on a weekly basis for information about specimens. He also published on fishes from Wealden, Purbeck and the Chalk. Much of his work helped to form the foundations of current research on numerous fish groups.

The Catalogue of Fossil Fishes, written by Sir Arthur Smith Woodward

Smith Woodward became Keeper of Geology in 1901 and spent his entire career here at the Museum, retiring in 1924 when he was knighted! He died in 1944. Over his lifetime he received many awards and medals including being made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1901 and the Lyell and Wollaston Medals of the Geological Society (there are actually too many to name here).

During the symposium we will have several talks about who he was as a person, his contribution to science and how his work has inspired generations of palaeontologists. There will also be poster contributions and a rare chance to see some of his type material described in the Catalogue and other key publications along with some of his many medals, which are kindly on loan to us from the British Museum.

The meeting will take place on Wednesday 21st May in The Flett Events Theatre of the Natural History Museum. Places are still available if you are interested and it is free to attend. However, you must register via the website.

Watch out for further posts about Smith Woodward and how the symposium went. We will also be working to produce a Procedings with a wide cross-section of papers next year. On the day I will be encouraging delegates to tweet and I will be doing the same from the Fossil Fish account and using the hashtag #ASW150.

Our snazzy logo for the symposium

Blog.jpg)

Blog.jpg)