Lichens grow almost everywhere – apart from the deep sea. As my blog has a lichen focus, it is high time I completed it! We picked up a field party at King Edward Point (KEP), South Georgia which provided new experiences to share with you.

We arrived at King Edward Point shortly after 11.00 a.m. on December 17. I checked my GPS. Sunset was at 7.57p.m. and sunrise 2.46 a.m.

Jessica, Malu, Bruce and I disembarked from the JCR together after lunch and set off towards Grytviken. The contrast in the weather since our earlier visit (October 29-30) was dramatic. Snow was scarcely to be seen. Summer had arrived. We certainly did not need to wear many layers!

After a brief visit to the museum where we borrowed ski poles to ward off potentially angry fur seals, we set off to explore our local surroundings. I climbed the slope behind Shackleton’s grave to the same area I had visited with Mick Mackey 6 weeks previously.

Photo taken above Shackleton’s graveyard on my way to Gull Lake.

I met Jessica and Malu walking towards Gull Lake. The lake was frozen when Mick and I last saw it and weather bitterly cold!

I explored the area for lichens and returned to the Museum.

South Georgia Museum, Grytviken, managed by the South Georgia Heritage Trust is located in stunning surroundings amongst spectacular relics of the Norwegian whaling industry. The museum was set up by Nigel Bonner, a former deputy director of the British Antarctic Survey, and opened in 1992. Nigel Bonner was also a Government sealing inspector in South Georgia in the 1950's and among other things undertook the first studies into the then endangered fur seals and reindeer. After his retirement from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) he returned to SG and set up the whaling museum. Tim and Pauline Carr took over the curatorship in 1992, extending the collection and displays to include the islands natural history, administration, exploration and expeditions and other related maritime history. The museum is visited by thousands of people every year.

I was welcomed outside the museum by Ainslie Wilson, its manager.

I was greeted at the entrance by a magnificent specimen of a wanderer (the wandering albatross), the bird with the largest wingspan of any in the world.

Large specimens such as wanderers and whale skeletons naturally excite everyone and take centre stage in virtually every museum. Imagine my surprise when I found the centre of this exhibit was occupied by much less well known and smaller organisms!

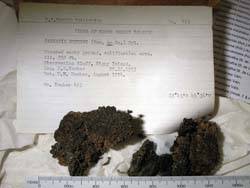

Lying next to a cute albatross chick on its nest is a charming selection of lichens, mosses and fungi which can be found in South Georgia.

A nice selection which whetted my appetite to explore for lichens in a new area – the plateau above the museum leading to Mt Duse.

I was greatly impressed by the range of exhibits, the well-illuminated displays and clear labelling. It was a most enjoyable visit. The museum and gift shop is a ‘must see’ for anyone visiting South Georgia. I do hope I shall be lucky enough to be able to visit again someday.

I was soon greeted by a spectacular fell-field carpeted by lichens, mosses and a tussock-forming grass within view of Mt Sugartop and Mt Paget (2934 m), the summit of Allardyce Range, the highest in South Georgia. Wonderful!

I am used to seeing reindeer lichen in Scandinavia and Scotland but did not see it on South Georgia on my previous visit when it was snowy. It is eaten by reindeer which have the right gut flora to digest its polysaccharides.

I admired a king penguin standing amongst dandelions on my return to the ship. Seeing the alien dandelions reminded me how little we know about how lichens are dispersed.

Visit to King Haakon Bay

A highlight of our sea voyage was certainly our visit to King Haakon Bay yesterday (December 18) which is challenging to navigate, rarely visited by BAS but a popular route for tourist ships who trace Shackleton’s voyages. We travelled overnight (12 hours averaging 12 knots) from King Edward Bay - a distance of ca 140 nautical miles. I was on deck shortly after 6.00 am as we approached the Bay. Here is a small selection of photos I took on this special day.

First photo I took (6.09 a.m.).

This is where Shackleton arrived from Elephant Island.

Ex-Signy mates, Jessica and Bruce.

Yellow lichens are readily visible on coastal rocks from the ship.

Blue-eyed, South Georgia shag.

It is now Saturday December 19. We won’t set foot ashore again until our ship arrives at Stanley in the Falkland Islands (scheduled for December 31) in time to catch a flight back to UK on January 1.

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

William is now en route home where he will begin working on the specimens and data he has collected during his time 'down South'.