On 25 June the Museum will open its doors to a special event in celebration of the international and global commitment between countries, industry, charities and academia to work together against Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs). This commitment was first agreed upon in London in 2012 and has since been termed the London Declaration On NTDs.

By joining forces to fight NTDs the world would achieve a huge reduction in health inequality paving the way to sustainable improvements in health and development especially amongst the worlds poor. The 25 June sees the launch of the third progress report, 'Country Leadership and Collaboration on Neglected Tropical Diseases'. A pragmatic overview of what has been done, what has worked, what hasn't and what key areas still need to be achieved.

The Museum is thrilled to be participating in this event, having a long-standing history in parasitic and neglected tropical disease research. As both a museum and an institute of research our mission is to answer questions of broad significance to science and society using our unique expertise and collections and to share and communicate our findings to inspire and inform the public. We are excited to be hosting a day of free public events on Neglected Tropical Diseases.

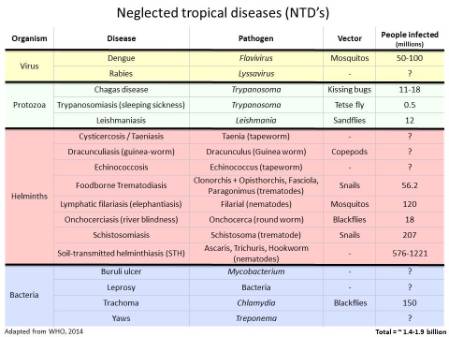

What are NTDs?

Neglected Tropical Diseases are termed in this way because they infect hundreds of thousands to millions of people, predominantly the world's poorest and most vulnerable communities, and yet receive comparatively little funding for basic, clinical or drug-development research and even less attention from governments, people and the media of affluent countries. Until now!

In total the WHO has identified 17 diseases or groups of diseases that fall within this category.

World Health Organization has identified 17 Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 of these have been targeted for control and elimination by 2020

The 10 selected by the WHO for control and elimination by 2020 are:

- Onchocerciasis (aka river blindness): A blood worm infection transmitted by the bite of infected blackflies causing severe itching and eye lesions as the adult worm produces larvae and leading to visual impairment and permanent blindness.

- Dracunculiasis (aka Guinea-worm disease): A roundworm infection transmitted exclusively by drinking-water contaminated with parasite-infected water fleas. The infection leads to meter-long female worms emerging from painful blisters on feet and legs to deposit her young. This leads to fever, nausea and vomiting as well as debilitating secondary bacterial infections in the blisters.

- Lymphatic filariasis: A blood & lymph worm infection transmitted by mosquitoes causing abnormal enlargement of limbs and genitals (elephantiasis) from adult worms inhabiting and reproducing in the lymphatic system.

- Blinding trachoma: A chlamydial infection transmitted through direct contact with infectious eye or nasal discharge, or through indirect contact (e.g. via flies) with unsafe living conditions and hygiene practices, which if left untreated causes irreversible corneal opacities and blindness. Trachoma is the leading cause of blindness in the word.

- Schistosomiasis (aka bilharzia): A blood fluke infection transmitted when larval forms released by freshwater snails penetrate human skin during contact with infested water. The infection leads to anaemia, chronic fatigue and painful urination/defaecation during childhood, later developing into severe organ problems such as liver and spleen damages, bladder cancer, genital lesions and infertility.

- Visceral leishmaniasis (aka Kala azar): A protozoan blood parasite transmitted through the bites of infected female sandflies which attacks internal organs which can be fatal within 2 years.

- Soil-transmitted helminths: A group on intestinal worm infections transmitted through soil contaminated by human faeces causing anaemia, vitamin A deficiency, stunted growth, malnutrition, intestinal obstruction and impaired development.

- Leprosy: A complex disease caused by infection mainly of the skin, peripheral nerves, mucosa of the upper respiratory tract and eyes.

- Chagas disease: A life-threatening illness caused by a blood protozoan parasite, transmitted to humans through contact with vector insects (triatomine bugs), ingestion of contaminated food, infected blood transfusions, congenital transmission, organ transplantation or laboratory accidents.

- Human African trypanosomiasis (aka sleeping sickness): A protozoan blood parasitic infection spread by the bites of tsetse flies that is almost 100% fatal without prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent the parasites invading the central nervous system.

They were selected because the tools to achieve control are already available to us and, for some, elimination should be achievable.

Take the Guinea Worm:

Guinea worm infection - from over 3.5 million people infected in the 80s to less than 130 cases in 2014. Set to be second human disease to be eradicated after smallpox (photo credits David Hamm&Peter Mayer)

In the 1980s over 3.5 million people were infected with Dracunculiasis (i.e. Guinea worm disease), with 21 countries being endemic for the disease. Now, thanks to the global health community efforts and extraordinary support from the Carter Center, only 126 cases were reported in 2014 and only 4 endemic countries remain: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali and South Sudan! If the WHO goal of global eradication of Guinea Worm by 2020 is met then Dracunculiasis is set to become the second human disease in history to be eradicated (the first, and only one, being smallpox). Not bad for an NTD! But there are still challenges!

At the Museum we have a long history of working on health related topics. Indeed our founding father Sir Hans Sloane was a physician who collected and identified plants from all over the world for the purpose of finding health benefits - in fact he developed chocolate milk as a health product.

Today we have a vast and biologically diverse collection of parasites and the insects/crustaceans/snails/arachnids that carry and transmit them. These are used by researchers both in the museum (such as myself and colleagues) but also internationally through collaborative work.

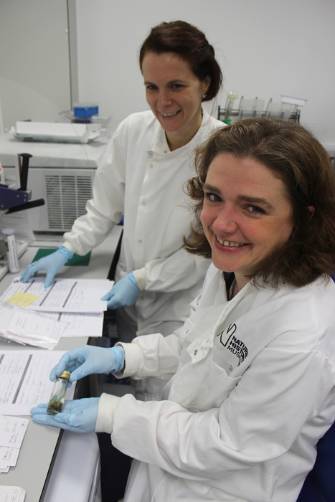

Collaboration is key - Zanzibar Elimination of Schistosomiasis Transmission (ZEST) programme key players: the Zanzibar Ministry of Health, Public Health Laboratories Pemba, the World Health Organization, SCI, SCORE, Swiss TPH, NHM and others

We are immensely proud of our collections and the work we do in this field especially of the biological information we can contribute to health programmes in endemic countries. One of our most exciting contributions is to the Zanzibar Elimination of Schistosomiasis Transmission (ZEST) programme where we are working in collaboration with the Zanzibar Ministry of Health, various NGOs, the World Health Organization and the local communities to identify and implement the best tools and methods to achieve schistosomiasis elimination in Zanzibar. This would be the first time a sub-Saharan African country would achieve schistosomiasis elimination. Fingers-crossed we are up to the challenge! You can read more about this project in an earlier post on our Super-flies and parasites blog

On Thursday we are bringing out our Parasites and Vectors specimens to showcase them to the public galleries and answer any questions relating to these fascinating yet dangerous organisms. Our wonderful scientists and curators will be on hand to talk to people about our collections and research as will collaborating scientists from the London Centre of Neglected Tropical Disease Research who will talk to you about the diseases and the challenges faced to achieve the WHO 2020 goals. Please do pop by and say hello, come and look at our specimens and help us raise awareness of these devastating diseases and the fight to control and eliminate them.

We are working together with schools, communities, government and research institutes to fight Neglected Tropical Diseases. Schistosomiasis fieldwork photo with the team from the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania

.jpg)