Before our field trip to the Isles of Scilly, I conducted the following short interview with Jo Wilbraham, an algae and seaweed specialist:

GA: Can you tell me about your fieldwork methods when collecting seaweeds?

JW: When searching the intertidal zone, we aim to spot all distinct species and collect samples where necessary for identification/voucher preservation. It is important to get an eye in for spotting seaweeds that look different, which probably are (but not necessarily) different species. Observation is the key to finding and recording species diversity. Photos of species in situ and the general habitat are very useful as are notes on observations in the field etc.

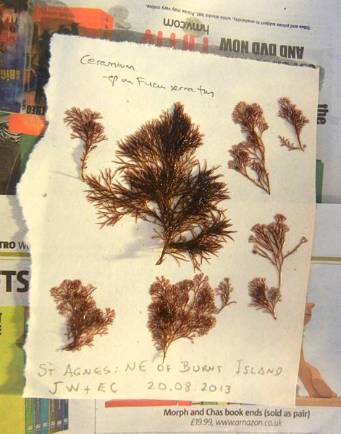

GA: What do you do with the specimen after it has been collected?

JW: We Identify the samples. We tend to take a microscope and ID book to the field station with us if possible, and work on identifications in the evening before pressing the specimens.

GA: Can drawing help to tune the scientist’s observation, benefiting their scientific fieldwork?

JW: Observation is critical in fieldwork as you are trying to visually pick out the species diversity of the group you are looking for against a lot of background ‘noise’. This is where drawing is very helpful and delineation can show important morphology and omit surrounding details. We never have much time as we also have to press the specimens/change wet drying papers etc. So there is no time to do drawings or extensive notes.

Shared methods

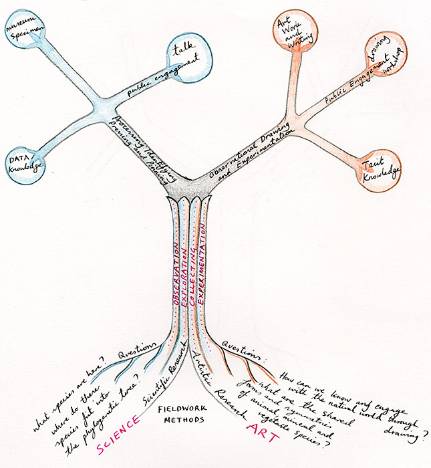

During the trip, the field methods of exploring, observing and collecting were shared by the artist and the scientist. It is the motivations, selection criteria and outcomes of the fieldwork that differentiate what we do.

Diagram showing where artistic and scientific fieldwork methods converge and diverge.

As an artist, I identify the morphological subset of forms within the specimen and then re-order and re-classify the specimen through drawing methods. I spend time with the specimen in it’s three-dimensional form, observing and drawing, building on my previous drawing and observational practice. The scientists take lots of photos of the specimen and then process it for the Museum collections, pressing plants into two dimensional forms and pinning insect material.

Although observation is still important in many scientific practices, the motivation behind observation in fieldwork is to identify the specimen (to name) and observational drawing is rarely prioritised in contemporary practice. I do not want to name the specimen, but to creatively explore it’s morphology through drawing methods in order to expand what and how I can know about the object.

Drawing the ‘uncollected’ fieldwork specimens

The collected fieldwork specimens are immediately pressed; their three-dimensional form squeezed into two dimensions before anyone - scientist or artist - has observed them in detail. It becomes clear that there is no time on fieldwork for the scientists to draw the collected specimens, or even for an artist to draw them!

But I am still determined to draw what the scientists have collected, and I decide to ask if I can draw the specimens that will not be taken back to the Museum - ‘the collected, uncollected’. These specimens, which have been brought together by the scientists, create a very unusual species combination at the field station. They are superfluous to the needs of this field trip, and would otherwise be thrown away as rubbish, so drawing them transforms them into a different material, it is a nice form of recycling!

Drawing leftover specimens: the etching process.

Drawing leftover specimens: the etching process.

I draw the specimens together to create a micro environment, where the work of the scientists and the artist combine. As an artist I am interested in how these specimens, which have been valued and subsequently devalued, can be re-valued and re-known through drawing practice; a practice which scientists are valuing less and less in contemporary scientific work.

A scan of the finished etching: 'Collected, uncollected'.

A scan of the finished etching: 'Collected, uncollected'.

I have explored these ideas further in my recent research paper ‘Endangered: A study of the declining practice of morphological drawing in zoological taxonomy’ (Published by Leonardo Journal, MIT Press 2013). I focus on the established drawing practice of three zoologists at the Natural History Museum in relation to my own drawing practice, adapted to the camera lucida device.

Posted on behalf of Gemma Anderson, an artist and PhD researcher who accompanied Musuem scientists on a field work trip to the Isles of Scilly between 17 and 23 August 2013.

.jpg)

.jpg)