Museum scientists Ashley King and Anton Kearsley have co-authored an article published in Science on 14 August 2014 on the first laboratory analysis of interstellar dust grains.

Have you ever wondered what exists beyond the solar system? Most people think space is empty, but in actual fact the vast regions between the stars, the interstellar medium, is full of tiny dust grains. Until recently the only way to study this dust was to use telescopes and we knew very little about its size, composition and structure. However, a new study has now described the first successful laboratory analysis of dust grains from outside the solar system.

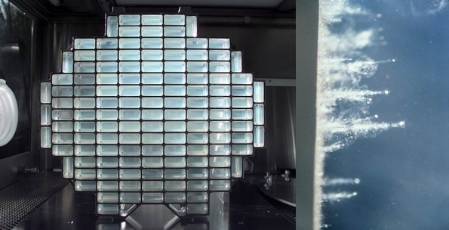

The interstellar dust was returned to Earth by NASA’s Stardust mission. Launched in 1999, the spacecraft had a collector made of aerogel bricks (the lightest solid material on Earth) in a frame made of aluminium. This was specially designed to preserve materials impacting into it at very high speeds (faster than 6 km/s). One side of the collector was used to capture materials from the comet Wild 2, the other to capture interstellar dust passing through the solar system. The sample-return capsule arrived safely back on Earth in 2006 and, following initial analysis of the comet grains, work began on the interstellar side.

The Stardust sample-return capsule landed in the Utah desert on 16 January 2006. The capsule was transported to Johnson Space Centre, Houston to be opened in a clean facility (Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The Stardust sample-return capsule landed in the Utah desert on 16 January 2006. The capsule was transported to Johnson Space Centre, Houston to be opened in a clean facility (Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The study reports the findings of a 6 year collaborative effort between 66 scientists (including myself and Anton Kearsley at the Museum) working in 36 laboratories in 7 countries. The team also received help from >30,000 members of the public who identified impacts tracks by searching through thousands of digital microscope images as part of the citizen science program Stardust@home.

It turned out that most of the impact tracks and craters were caused by debris from the spacecraft or dust from within the solar system. However, 7 grains are likely to be of interstellar origin and, using the experience gained from examination of the comet particles, the team developed methods for extracting, handling and analysing the precious interstellar samples, finding some unexpected results along the way!

Tiny dust particles impacting into the collector (about the size of a tennis racket) produced tracks in the aerogel (right) and craters in the Al-foils (Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech).

Tiny dust particles impacting into the collector (about the size of a tennis racket) produced tracks in the aerogel (right) and craters in the Al-foils (Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The interstellar grains are very small, typically weighing a picogram (a millionth of a millionth of a gramme) or less, and have different compositions and structures. One of the biggest discoveries is that the grains have at least partly crystalline structures, which is surprising as most people thought that the crystallinity should be destroyed in interstellar space by irradiation.

Sample-return missions such as Stardust are therefore allowing us to answer big questions about the formation and evolution of galaxies and solar systems by studying minute amounts of material in the laboratory. The Science paper has just hit the headlines today but, hopefully, there's a lot more to come in this story.