We left João in Ilhéus to catch his plane back to Belo Horizonte, while we spent the afternoon in the herbarium at Centro de Pequisas do Cacao (CEPEC: Chocolate Research Centre) looking at new collections from Bahia – what a rich collection! Bahia is very diverse, and the collectors in the herbarium are very active, so we found many new localities for species we are interested in.

Lynn readying herself for identifying specimens in the CEPEC herbarium.

Next morning we woke to torrential rain, and headed out to a private reserve called Serra do Teimoso, a bit further south than Ilhéus. This is a very rainy place – and it rained the whole way there, with a few breaks where the sun shone and we collected a few plants along the road. We passed through cacao plantations (this is a big cacao growing area) – they leave the tall trees and underplant with cacao. From the road it looks a bit like good forest – and it is for some animals, not for understory plants though.

Cacao (Theobroma cacao, first described by Linnaeus) grows as a small tree in the shade of the forest canopy.

We reached the private reserve Serra do Teimoso in the pouring rain, but found our little house and got settled in. The accommodation was luxurious – a bedroom each with sheets and towels, electricity, and all with the accompaniment of birds and cicadas, only the noises of nature.

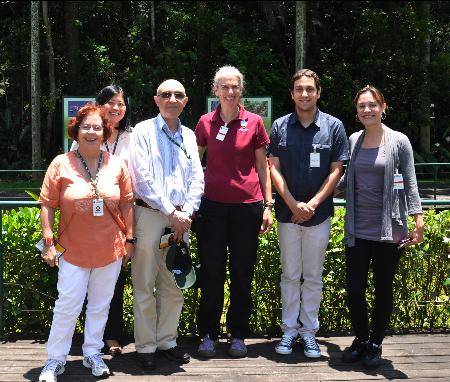

Lynn and Leandro getting settled in before we set out for the field – hoping it stops raining!

The main reason we had come to Serra do Teimoso (other than it is a very nice piece of forest) was to find the extremely rare Solanum paralum. This was one of the species Lynn had studied for her PhD, but she had never seen it in the field and it had not yet been included in any study of evolutionary relationships in the group. So it was a real target…

It might seem odd to be looking for things we know about already, but it is really important to see an organism in the field to understand how it fits into the grand scheme of things. For one thing, plant form is not well preserved (well, not at all!) on flat 2D herbarium sheets, collectors often write down incorrect or misremembered information about plant height or shape, flowers often have particular scents, and you often find associations with insects or other plants. Also, specialists in a group are the keenest observers of differences or similarities, and these are more often apparent in the field.

To get to Solanum paralum though, we had to climb the mountain – and there was not enough time on day one of our stay in Teimoso. We spent the afternoon looking in vain for other Solanaceae near the base of the mountain in a torrential rainstorm – it rained buckets! Rarely have any of us been so very wet….

The Serra do Teimoso in the rain – we certainly hoped it would let up for the next day's collecting!

It kept raining most of the night – because it was so wet we had visitors. This little frog was nicknamed Ha-Ha by Lynn – a play on the word for frog in Portuguese ‘rã’, pronounced with a guttural r. There were many beautiful moths by the veranda light, its times like these I wish we were with a large team with other specialities (see Alessandro's Lepidoptera blog). But travelling with other solanologos (Solanaceae lovers!) is great – everybody is happy about the same things and no one is disgruntled having to wait for someone else to find his or her organisms.

I am not sure of the identification of this lovely frog; it was about 4cm long and landed with a plop whenever it jumped!

It dawned perfectly clear and sunny – amazing – we took this to be a good sign. So off we set in search of Solanum paralum. Our guide, Francisco, was a bit uncertain as to whether or not there was a trail to the top, no one had been here for about 3 years – his observation was “it is very far and difficult, and there is probably not a trail anymore”.

But we were insistent and so off we set. Indeed there was no trail, well at the bottom there was a faint track through the forest, but once we began to climb – nothing at all. We followed a ridge, basically straight up, but with many detours getting a bit lost and having to go round huge treefalls.

Francisco was amazing – he made us stop every now and then so he could investigate, but he knew just where we were going – more or less. The treefalls were the worst – the trees here are very large, we saw some as big as almost a metre in diameter, so when they fall they leave a big tangle to get around.

To get across these areas you have to cut a path through thick secondary growth that springs up where light reaches the forest floor once a big tree falls.

The forest going up the ridge was drier than we had expected, and was full of prickly vines and members of the mulberry family (Moraceae). We did find our friend Solanum bahianum, and an absolutely beautiful passion flower – growing straight out of a corky stem about 2cm in diameter.

This Passiflora is a huge canopy vine; the flowers are asymmetric, so its identification will probably (?) be pretty straightforward once we are back in the land of botanical literature!

After several hours of climbing straight up we came to a place where the vegetation changed completely – no more mulberries and the understory was full of large monocots like Heliconia and Panama hat palms (not really palms, but Asplundia species in the family Cyclanthaceae). And there it was – a small sterile plant of Solanum paralum! It is easy to recognise by its fleshy, slightly blue-green pinnate leaves.

Our first find of Solanum paralum with Francisco as scale – the plant was actually sprouting from a fallen stem.

Everyone, especially Lynn, was pretty excited even though there were no flowers and fruits. So we scouted around to see if there were more plants – this species is known from only a very few collections so we were expecting it to be rare. Alternatively, it might be known from so few collections because it is incredibly hard to find!

Francisco found another sterile stem, but when we looked down the hill we saw it was again from a fallen tree and that farther up the stem there were branches with flowers and fruit! The tree itself was about 6m tall and about 4cm in diameter – Solanaceae often have very soft wood but this species seems to topple over an awful lot, maybe it is something to do with the very wet habitat as well.

We made a number of duplicate specimens for other collections – with something this rare it is important that it is represented in many herbaria. Since it was a tree we only took a few branches, and we left some of the ripe fruit for the forest…

The flowers of Solanum paralum smelled like a strong perfume – not like anything else, but very strong smelling. This comes from the enlarged back of the anther (the dark purple bit) that produces scent that is collected by male bees for use as an attractant; a very specialised pollination system. The petals were also covered with fine glandular hairs, and the parasol-shaped stigma (for which Lynn named this plant) was really obvious.

The fruit we found were absolutely ripe and full of pale orange pulp. Solanum paralum is related to the tamarillo, but the fruit did not taste as good. Not bad though, according to Lynn!

In the same area we also found a Brunfelsia growing in the understory in deep shade. We can’t figure out what species it might be, so will have to wait until we get back to the herbarium and library to do some careful comparison.

Brunfelsia species often grow in a very dispersed way, one here one there. This was the only plant we found in bloom, but we saw other sterile ones. The flower tube was almost 4cm long

So what a plant was Solanum paralum!! Impossibly hard to get to and such a find – the trek was totally worth it.

If anything, the way back down was harder than the way up, we were all a bit amazed at the steepness of it. It didn’t feel that steep climbing up! Near the bottom, where there was actually a trail again, Leandro decided to climb to the canopy platform (Lynn and I bottled it – neither of us are fond of heights).

The platform is about 30 metres up in a tall leguminous tree, the straight up ladder looked a bit scary to me!

Leandro came back with amazing photos – he says this rainbow’s other end was at the Solanum paralum collecting site, something I quite believe (picture courtesy of Leandro Giacomin).

Looking back up the mountain at the end of the day it didn’t seem like we went that far. But it was a hard couple of days. The end result makes it all worthwhile though and that is one of the joys of collecting, seeing plants in their native habitat increases our understanding, but also appreciation for the richness of plant life. And that is why we all got into this business in the first place; it is trips like this that remind me how lucky I am to be doing what I do!