The re-housing of the Museum’s hawkmoths collection, one of my curatorial responsibilities, has been the subject of the last couple of posts. I talked about the transferring of specimens from outdated or transitory drawers into new, more permanent drawers, and of the amalgamation of the old Museum’s collections with newly acquired material, with particular reference to the collection of hawkmoths (Sphingidae).

I have also introduced some of the species from the Museum’s extended sphingid collection, consisting of around 289,000 specimens and, in this post, I would like to briefly tell of the history of the Museum's collection of hawkmoths. However, before I start delving into the past, I’d like to finish with the introduction of some of the species of hawkmoths I began in the previous post… so here are some other fascinating sphingids.

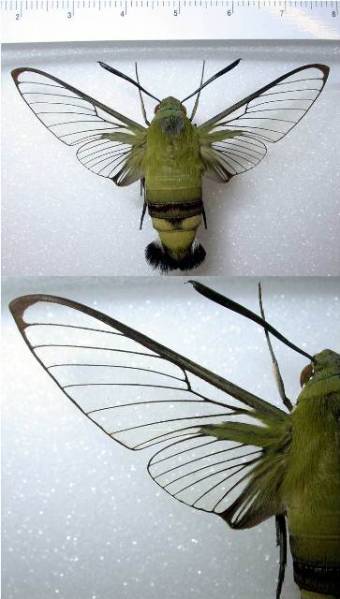

Some hawkmoths have a short and stout body, transparent wings, a distinct pattern and behaviour that make them look like bees or wasps.

This is Cephonodes hylas, a daily flying moth, widely distributed in Asia where it is often found in urban parks and gardens attracted by Gardenia, one of the caterpillar's food plants. When the adult moth emerges from the pupa, the wings are entirely covered with greyish scales. These come off in a little cloud after the first flight.

Another hymenoptera look alike is Hemaris fuciformis.

This little and pretty hawkmoth, with its plump body covered by yellowish and reddish hairs, and its transparent wings, looks very much like a bumble bee, and it flies rapidly like one too! This specie is widespread all over Europe eastward across northern Turkey, northern Afghanistan, southern Siberia, northern Amurskaya to Primorskiy Kray and Sakhalin Island. It has also been recorded from Tajikistan and northwest India.

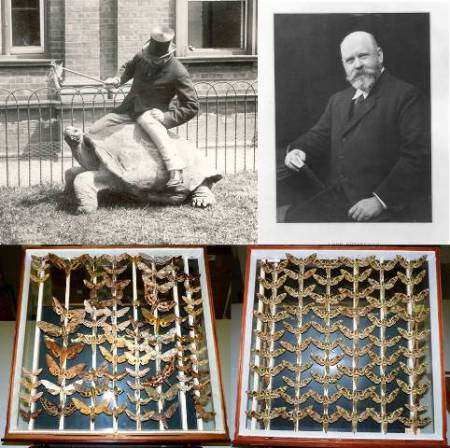

Sataspes infernalis is another daily flying hawkmoth that very convincingly mimics a carpenter bee.

Its wings are devoid of scales and are darker, more opaque and somehow iridescent compared to the previous two hawkmoths. This species is distributed in India, West China, Burma and Borneo.

Eye-spots are a common feature on the wings of Lepidoptera and hawkmoths are no exception. This stunning hawkmoth is Compsulyx cochereaui, an endemic species of New Caledonia.

Eye-spots are also found on the hind-wings of the species of hawkmoths belonging to the genus Smerinthus.

This genus includes 11 species and one of them is the eyed hawkmoth (Smerinthus ocellata). In the resting position the fore-wings cover the hind-wings with the eye spots, when the moth feels threatened, the fore-wings are suddenly pushed upward revealing the hind-wings decorated with intense blue and black 'eyes' on a pinkish and brown background.

The flashing of these false eye-spots may help in startling a potential predator giving the moth a chance to quickly fly away. The eyed hawkmoth is distributed across all of Europe (including the UK), through to Russia as far east as the Ob valley and to eastern Kazakhstan and the Altai. It has also been recorded in north and western China.

Pseudandriasa mutata is a rather atypical sphingid

It doesn’t look particularly streamlined nor are its wings elongated like those of a typical hawkmoth. In fact when in 1855, Francis Walker - while studying specimens and describing new species from our Museum - came across a specimen of this hawkmoth, he recognized it as a new species but named it Lymantria mutata, thinking it belonged to the family of moths called Lymantriidae (Tussock moths).

Hayesiana triopus is a lovely daily flying sphingid with translucent wings and a discontinuous pinkish-red belt and orange spots on a black abdomen.

The underside of the body, particularly of the thorax, abdomen and hind wings is reddish orange. This moth is a fast flyer but its rapid movements seem rather clumsy and, apparently, it's not particularly precise when aiming the proboscis into a flower. It is distributed in Nepal, northeastern India, southern China, and Thailand.

Callionima inuus is certainly a very elegant hawkmoth thanks to the decorations on its forewings.

The scale pattern forms motifs which resembles a cover of cobwebs blended with small, dark and light brown wavy markings; there is also a patch of silver scales in the shape of a plump and twisted “Y”. The pattern is beautiful, but most of all indispensable, for perfectly disguising this moth in the environment where it lives. This species is well distributed in the entire Neotropical region, from Mexico to Argentina.

Another master of disguise is Phylloxiphia oberthueri.

When in the resting position, hanging from a plant, this hawkmoth looks very convincingly like a bunch of dry leaves. This species is distributed through West Africa.

Doesn’t Hypaedalea insignis look like the vehicle of a superhero character?

An innovative hawkmoth bat-car! But again, this pattern has not evolved to impress we humans; the amazing discontinuous and wavy lines and blotches, coloured with different tints of brown and grey, are all essential for making this hawkmoth hard to spot against the vegetation. This moth is distributed in West Africa.

And now, the history bit...

The Museum's collections are based on Sir Hans Sloane’s collection which was purchased by the British Museum in 1753. Amongst them were his entomological holdings, with around 5,500 specimens including Lepidoptera, and thus were the earliest Sphingidae housed in the Museum.

A drawer with specimens of Lepidoptera from the original collection of Sir Hans Sloane. The hawkmoths in this drawer (Smerinthus ocellata in the top left, Agrius convolvuli and Sphinx ligustri bottom left and right respectively) were collected more than 350 years ago and are amongst the oldest Lepidoptera specimens in our collections.

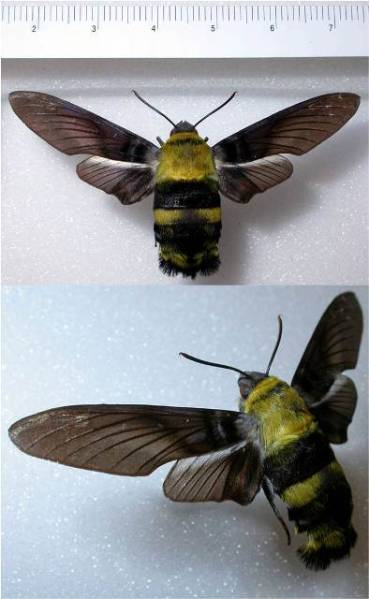

Afterwards, the earliest and most significant benefactors who presented Lepidoptera - and particularly Sphingidae - to the Museum were, Horsfield, the Honorable East India Company, and Museum appointees like Edward Doubleday.

Later 19th Century benefactors of major significance were Bates, Wallace, Stainton, Zeller, Bainbrigge-Fletcher, Hewitson, Leech and Godman and Salvin. And in the 20th Century the sphingids holdings of the Museum were to be enriched with the collections of Lord Walsingham, Swinhoe, Moore, Joicey, Levick, Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild, Cockayne and Kettlewell, Inoue and others.

Some of the most significant donors of Lepidoptera (and particularly of Sphingidae) to the Museum.

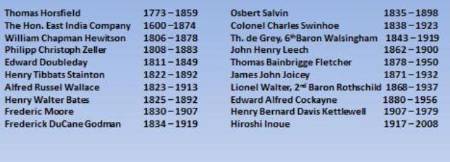

The date of acquisition, the number of specimens and some of the history behind each of these valuable collections of moths and butterflies is often well documented, but it is much more difficult to know the exact number of specimens of any particular family that came with any of them. However, we know that the majority of the hawkmoths - around 45,000 specimens - came to the Museum in 1939 when Lord Rothschild bequested approximately 2.5 million specimens of Lepidoptera.

Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild was a keen naturalist who went on to amass one of the greatest collections of animals ever assembled by an individual. In 1939 around 2.5 million specimens of butterflies and moths from the Rothschild collection, were entrusted to the Museum in thousands of drawers. Two of these drawers, containing hawkmoths, are shown in the picture.

The Sphingidae collection, like the majority of the other Lepidoptera families, has since 1904 been housed in the Museum in 4 separated blocks:

The Main Collection.

This is the reference collection and contains drawers with type specimens and representative series of any particular family, often of the oldest material. In the picture, one of the main collection drawers with the hawkmoth Callionima inuus.

The Supplementary Collection.

It contains other specimens, belonging to any particular family, of identified material which arrived later and for which there was not space in the main collection. In the picture, one of the supplementary drawers with the hawkmoth Agrius convolvuli.

The Accession Collection.

It contains unsorted and often unidentified material which was later added to the family. In the picture, one of the accession drawers with different species of hawkmoths from the original Rothschild Collection.

The British & Irish Collection.

It contains specimens of the 20 species of Sphingidae occurring in the British Isles. In the picture, one of the British and Irish Collection drawers with the hawkmoth Daphnis nerii.

Only relatively recently we began to amalgamate all specimens from the main, supplementary and accession collections into one collection for each family. Each of the 5 curators in the Lepidoptera section is responsible, amongst other things, of the re-housing of one or more families of moths and butterflies.

With a collection of almost 9 million specimens and around 135 families of Lepidoptera to take into account the work to do can seem endless; it will certainly take a long time and a lot of effort before this is accomplished, but slowly and surely we are improving the care, storage and accessibility of our collections.

In August 2008, thanks to the generous sponsorship of the Rothschild family, the de Rothschild family, the John Spedan Lewis foundation, Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust and members of the public, the Museum was able to acquire one of the largest private collections of Sphingidae, the Jean-Marie Cadiou collection.

And it’s about this prodigious private Collection, containig a staggering total of around 230,000 specimens, the majority of which are sphingids, that I will be telling you in my next post. Make sure to come back then.

Thanks for reading.