My post for today shall begin with a clip of what we've been priviledged to see every day whilst on field work in Mexico. Lee, Dave and I are all keen photographers and agree that there's a picture wherever you look. The light is literally perfect and there's barely a sound (bar that of scientists chipping rock) that can be heard in these wide expanses of grass, pines and volcanic matter.

(Note: this video has no sound)

After a high buzz start to the day, linking live to our Attenborough Studio to take excellent questions from sweet, keen students in a special event for schools, we visit our next outcrop (an area of exposed rock), a beautiful area called Tlamacas at 3,900m above sea level. No sooner had we piled out of the jeep than we see the cheery sight of Hugo, springing up like a mountain goat, to rocks roughly 10 metres high. I ask him as he descends a little later what is the highest he's climbed. 'K2', he beamed, 'at 7,300m.' I feel my lungs tighten and my admiration grow.

Hugo and Chiara investigate. Popo watches on in the distance.

I approach Dave to nosey into his activities by the exposed rock face. What have we here then? 'Volcanic rock. Feldspar. The likes we've seen here already. It's called Dacite.' I look on as he photographs the rock and ask how these images are then used. 'Pictures go alongside the collections. They show the features of the flow.' This has a snappy ring to it but a lot of sense too. Unfortunately Dave does not receive the same kind of imagery with samples given by others to the collection. 'If only' he smiles.

I'm keen to know what finding similar rocks means in different outcrops. 'It's unusual not to have lots of change in a volcano but Popo's rocks so far are fairly similar. Chemistry should change over so many hundreds of thousands of years but they've not done so much here. The whole process is a bit random, so change should occur. This makes Popo pretty interesting.' The team chip away samples and discuss their finds. Hugo and Chiara pass samples between each other until Chiara pleads with hands full. 'Poor Italians, you only have two hands' laughs Hugo.

Chiara takes five to speak with Hugo's University TV Crew.

Our second outcrop is but a walk away. A steep walk. Downwards. Chiara must have some idea of how steep and she looks apprehensive. Her apprehension makes me excited. Are we going on a difficult hike? Hugo takes us to a spot, points down and says he'll meet us at the bottom. 'Don't follow the river for long as there are cascades. I'll meet you down there.' Our springy mountain goat not coming? Then I'm with Chiara on this one.

Cascades you say? Dave and Chiara following the river. And by river they mean where it used to be. I was looking for water. Doh.

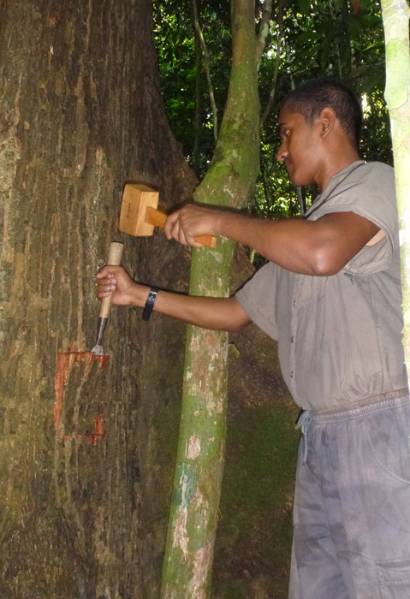

I discover the senses figure highly in rock collecting. Firstly, as I sniff a fresh surface of exposed rock I discover that licking them is an everyday geologist pastime. Why? 'To taste the minerals' says Chiara, which seems a reasonable enough idea. Soon after I see Dave shaking his head in disapproval as he hammers a rock face in several places. 'No, no, no' he says as he slings the 'bad' rocks to one side. What gives, Dave? Well, sound is important too it seems. 'The thing you want is kind of a tinny sound when you hit it. Means its hard, unweathered and fairly fresh.'

You go first. No, you go first.

Our search for a particular rock named ignimbrite reaps little rewards. An incredibly weathered outcrop is what we discover and this is impossible to sample usefully. We have, however, tested our fitness by climbing down pretty much a vertical slope, zig-zagging all the way. Thank heavens the high altitude grasses or Sacaton are strong rooted or this reporter would be no longer with you. We stop, eat chocolate and ponder our route to meet up with Hugo.

Our first evidence of large mammals as we hike our way to meet Hugo.

The compass looks right, the road looks semi-alright (in two places we duck under barbed wire to continue) and we feel confident of our direction to the jeep. An hour passes and Chiara seems slower and more laboured. We check on her health and she admits to feeling the altitude as she takes out her inhaler and calms her asthma. Dave and I have headaches. Unusual and intense.

We continue more slowly and Chiara hangs back to throw up in the most polite way I have ever seen. There's no doubt it's moderate altitude sickness. A few more stops and Hugo hoves into view. Exhausted glee. It's back to base and straight to bed after a long day in the field.