On 13 Feb a new temporary exhibition opened here at the Museum entitled Britain: one million years of the human story. It includes some images of microfossils from our collection in the display.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of pollen grains from our collection that appear in the exhibition.

These and other microfossil collections housed behind the scenes help with dating the finds, reconstructing the environment, landscape and climate of these first human settlements in Britain and provide the climatic context for the recent discovery of the earliest human footprints in Britain on a Norfolk beach.

The AHOB Project and micropalaeontology

The exhibition highlights the work of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain (AHOB) Project and its predecessor projects. The current project, funded by Calleva, is investigating the timing and nature of human occupation of the British Isles, the technology they used, their behaviour, the environment they lived in and the fauna sharing the landscape. The microfaunas and floras mentioned here were recovered by project researcher Mark Lewis and project associate member John Whittaker.

Mark is a palynologist and has used the distribution of pollen grains in the sediments surrounding the human finds to interpret ancient climates and landscapes. Pollen grains that range in size from 10-100 microns can be found in sediments millions of years after the plants that produced them have died and decayed.

The Museum collections

Mark regularly uses our collection of modern pollen and spores to interpret the pollen floras that he recovers as part of the AHOB Project. We recently transferred this collection from the Botany Department and the images in the exhibition were taken from the collection of SEM prints and negatives that accompanies that collection.

Part of our modern pollen collection. Slides are housed in special plastic sleeves and arranged by plant family name.

John Whittaker spent his entire career as a researcher here at the Museum and is a now a Scientific Associate in the Earth Sciences Department as well as being an Associate Member of the AHOB Project. In a previous blog post I highlighted his microfossil finds from three key early human sites at Boxgrove about 500,000 years old, Pakefield about 700,000 years old and Happisburgh (prounced Haze-boro) about 900,000 years old. Many of John Whittaker's microfossil slides are deposited here at the Museum.

Ancient landscapes

The pollen grain illustrations from the exhibition were chosen because of their use and importance in reconstructing ancient environments, particularly the vegetation dominating the landscapes in which the ancient humans lived. The scanning electron microscope images shown above from left to right are:

1. Dandelion-type e.g. Taraxacum - this herb indicates dry grassland or disturbed open ground

2. Dwarf willow, Salix herbacea - characteristic of rocky, open ground as found during cold periods

3. Montpellier maple, Acer monspessulanum - currently native to the Mediterranean and central Europe, this tree was present in Britain only during the last (Ipswichian) interglacial about 125,000 years ago

4. Bogbean, Menyanthes trifoliata - shallow water inhabitant of bogs and fens during both temperate and cold periods

5. Common valerian, Valeriana officinalis - herb indicating either dry or damp grassland as well as rough ground

Environments of deposition of sediments

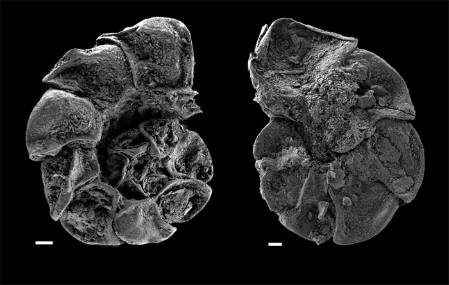

Ostracods and Foraminifera collected by John Whittaker from Boxgrove indicate a marine raised beach and a later terrestrial deposit with freshwater ponds below chalk cliffs.

The saltmarsh foraminiferal species Jadammina macrescens has been recovered from Happisburgh and is consistent with interpretations that the site is situated near the mouth of the ancient large river, possibly the River Thames.

The foraminiferal species Jadammina macrescens is common in saltmarsh environments.

The foraminiferal species Jadammina macrescens is common in saltmarsh environments.

The microfossils were able to show that the Slindon Sands were deposited in a wholly marine high-energy environment, whereas the Slindon Silts were deposited in a shallow intertidal environment at the margin of a regressive sea. This sort of information is vital when interpreting the archaeological finds from the site.

Ancient climates

River sediments containing flint artefacts have been found on the coast of East Anglia at Pakefield. The oldest artefacts came from the upper levels of estuarine silts where both marine and brackish ostracods and foraminifera have been recovered.

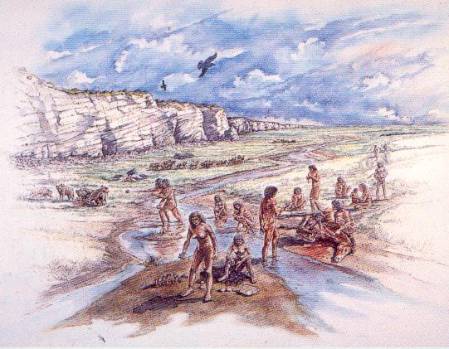

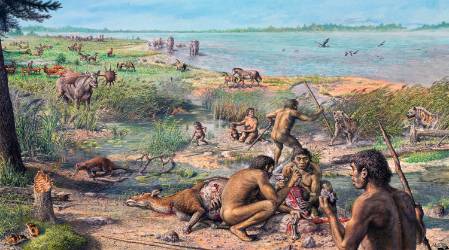

Reconstruction of a scene at Happisburgh about 900,000 years ago by John Sibbick. (copyright AHOB/John Sibbick)

Other evidence from mammal, beetle and plant remains suggests a setting on the floodplain of a slow flowing river where marshy areas were common. The river sediments were deposited during a previously unrecognised warm stage (interglacial) and the presence of several warmth loving plants and animals suggests that the climate was similar to that in present day southern Europe.

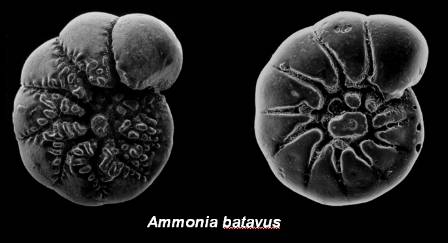

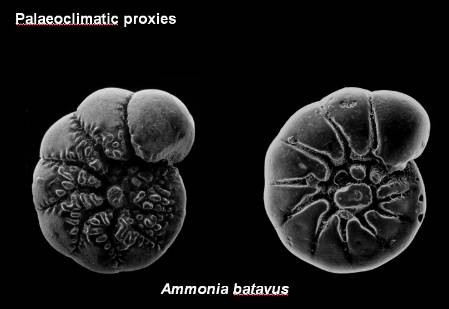

Pollen and mammal fossils recovered from Happisburgh suggest that the climate was similar to that of southern Sweden and Norway of today with extensive conifer forest and grasslands. The floodplains were roamed by herds of mammoth and horses. Foraminifera such as the species Ammonia batavus are characteristic of warmer climates.

Evidence of reworking of some sediments

The interglacial sediments at Pakefield are overlain by a thick sequence of glacial deposits which include till and outwash sands and gravels. These contain reworked (Cretaceous and Neogene) microfossils transported from the North Sea Basin by glaciers. This is important information as fossils found in these redeposited sediments could be give false indications as to the climatic setting and dating of any finds.

Dating deposits

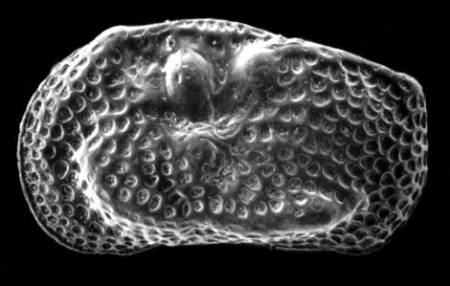

The dating of the deposit at Happisburgh is provided by a combination of mammoth, horse, beetle and vole finds as well as the Middle Pleistocene ostracod Scordiscia marinae. Work by John Whittaker and the AHOB team at a number of other Pleistocene sites across the SE of Britain has increased the potential of ostracods as tools for dating these sediments.

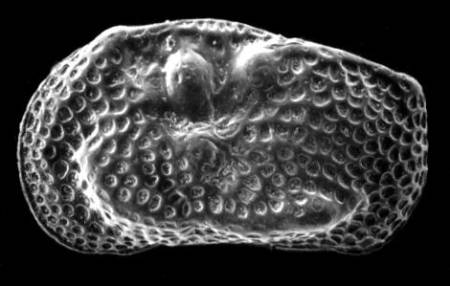

The extinct freshwater ostracod Scordiscia marinae has been found at both Pakefield and Boxgrove and is

characteristic of the Middle Pleistocene period. An example of a microfossil that is useful for dating sediments.

Earliest footprints

A flint handaxe recovered from sediments recently exposed on the foreshore at Happisburgh provides part of the evidence for the earliest human occupation of Britain. Several other Palaeolithic sites have since been discovered there including sets of early human footprints on the foreshore that made the national news at the time of the opening of the exhibition.

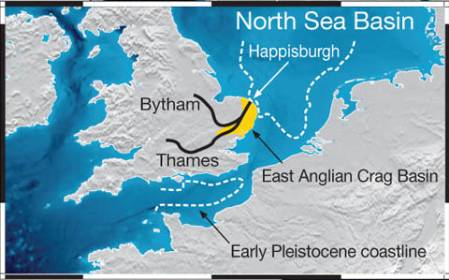

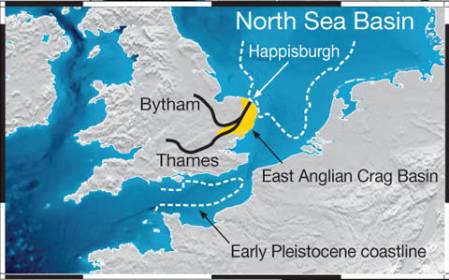

A Palaeogeographic map of Britain the in Early Pleistocene showing the land bridge between Europe and the position of the Thames and Bytham rivers. (Courtesy of Simon Parfitt and the AHOB Project)

Pine (Pinus) and spruce (Picea) pollen recovered by Mark Lewis from the sediments that preserved the Happisburgh footprints.

Pine (Pinus) and spruce (Picea) pollen recovered by Mark Lewis from the sediments that preserved the Happisburgh footprints.

Pollen analysis of the sediments adjoining the footprints revealed the local vegetation consisted of an open coniferous forest of pine (Pinus), spruce (Picea), with some birch (Betula). There were some wetter areas where Alder (Alnus) was growing; patches of heath and grassland were also present. These all indicate a cooler climate typical of the beginning or the end of an interglacial recognised at other Happisburgh sites.

Come and see the exhibition

I would recommend that you come and see the exhibition Britain: one million years of the human story if you can, before it closes at the end of September. If you can't then there are a wealth of interesting items on the Museum website including a video showing the recently discovered footprints.

Quite rightly the artefacts and larger fossil materials collected from these early human sites in Britain dominate the exhibition along with the amazing life-sized models like 'Ned the Neanderthal'. Hopefully this post has shown that there are many other undisplayed collections held behind the scenes here at the Museum that are just as important in telling us how, when and where the earliest humans lived in Britain.