For obvious reasons I have always wanted to do fieldwork on Pulau Langgun, one of the islands that make up the Langkawi Islands off the far NW coast of the Malaysian Peninsula. In my last post I described the difficulties of interpreting the geology of the Malaysian Peninsula and how we were attempting to use conodont microfossils to answer some of the questions by dating the isolated rock exposures.

We travelled to Langkawi Island to sample conodonts from the most complete exposure of rocks in the region as it will act as a reference section for our student Atilia Bashardin and help to interpret the isolated rock exposures on the mainland. The islands are also where the conodont Panderodus langkawiensis was first described and this species was a target for our collecting.

For two days our field vehicle (above) left us on the coastline early in the morning. The unfavourable tides meant that we only had three hours on the section before our boat had to come and pick us up.

The early morning trip to the section was amazingly picturesque as we motored through mangroves and past imposing forested limestone crags. On the first morning we encountered dolphins as we moved out into the open water.

This was our first sight of the study section from the sea. Initially it was difficult to see any rock exposures as they are hidden behind the margins of the forest that encroaches the beach. We landed at the end of the pier that you can see to the right and made our way along the coastline to the left.

This is a typical limestone exposure in the area. Despite the idyllic setting, it is quite hard work to sample here. In my previous post I described how you usually need several kilogrammes of rock to find conodonts. Here the surfaces are very weathered leaving some beds standing proud. Unfortunately it is the recessed, weathered parts of the beds that we needed to collect as these will most easily dissolve in acetic acid (vinegar).

Microfossils can be recovered from most sedimentary rocks but it is important to choose the correct part of the rock to sample in order to maximise the yield. This often requires interpretation of the environment in which the rocks were originally deposited. It is not possible to know while sampling if a particular bed will yield conodonts and sometimes even an experienced eye can be wrong.

We are sampling here because these beds have previously yielded conodonts according to a paper published in the late 1960s and a recent study by a University of Birmingham undergraduate student.

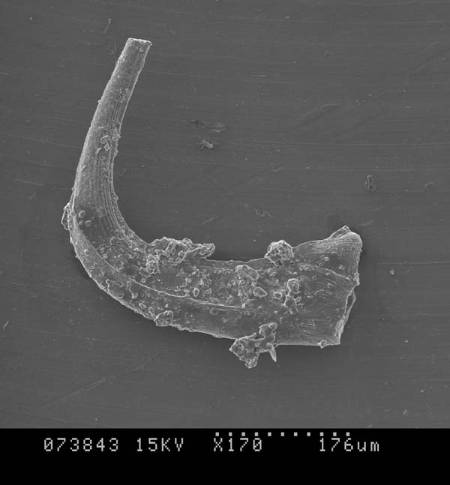

A scanning electron microscope image of an element from the apparatus of the conodont Panderodus langkawiensis recovered from one of the samples processed by John Lignum, former University of Birmingham undergraduate. The dotted scale bar at the bottom is 0.176mm.

This is a rare blog picture of the 'Curator of Micropalaeontology' looking rather sweaty and muddy after an extended session with the geological hammer. The words on the pier behind say 'Teluk Mempelam' which means Mango Bay. Unfortunately there were no mangos to be seen.

In a 2005 paper published by two of my retired colleagues, Robin Cocks and Richard Fortey, the old name for the limestone here the 'Upper Setul Limestone Formation' was changed to the 'Mempelam Limestone Formation'. They studied the distribution of invertebrate fossils of this region, particularly the brachiopods and trilobites, to interpret the geological history of the region. Many of the collections that back up these findings are housed in the Museum.

Initial findings from the conodonts have provided more precise datings for some of the newly named geological formations suggested by Cocks and Fortey. It will also be interesting to see if the Mempelan Limestone Formation can be traced to the mainland.

Not all the rocks on this coastal section were easy to swing a hammer at. Here Atilia is looking pleased with herself as she has managed to collect a nice lump of limestone from this rock exposure where previously I had failed! I had told her to give up but her persistence was rewarded.

Here are two of our Mempelam Limestone Formation samples with a view of the section in the background. These samples were too large to fit in our standard sample bags so we had to label them with indelible marker pen and carry them back to the boat by hand. The surface is pitted from weathering and some of the edges were quite sharp so they were quite difficult to carry.

Dr Aaron Hunter (right) is pictured here with Universiti Teknologie PETRONAS undergradate student Vittaya Boon (left). He joined us on the trip as he is lucky enough to be doing his undergraduate project on Pulau Langgun, Langkawi. The two large cool boxes on the trolley were packed full of the limestone samples we collected.

On the way home we gained a flat tyre and ended up having the valves on all four wheels replaced! Perhaps the extra loading from a heavy box of rocks caused this mishap? Emma and Aaron are seen here surveying the damage. A big thank you is due to Emma who drove us throughout the fieldtrip with an enormous amount of skill, concentration and patience.

The title of this blog was designed to make you want to read on and not meant to imply any slackness on our part . Hopefully over the last two blogs I have shown how conodonts can play a major role in Palaeozoic (roughly 500-200 million year old) geology by providing palaeotemperatures, palaeoenvironments and most importantly datings for rock successions. This fieldwork has also been an excellent example of the Museum developing links with international universities, providing teaching while expanding our collections from this geologically important region of the world.