Posted on behalf of Erica McAlister, Curator of Diptera at the Natural History Museum.

I've just recurated an entire family of flies – and in only three days! It's not often I can do that (I have been recurating the world bee-fly collection for over three years now and it's still ongoing), but then there were only 14 species of this family in the Natural History Museum collection. That doesn't sound like a lot, but after all the shuffling around over the last 40 years with the taxonomy there are only 20 described species within 2 genera.

So in terms of species numbers, it’s a very small family... but in terms of individuals, they are far from small. The family I am talking about are Pantophthalmidae, and they are some of the largest flies on the planet (although I think that Mydidae can rival them). There is no real common name; they are more often than not shortened to Pantophthalmid flies, but are sometimes referred to as timber flies or giant woodflies.

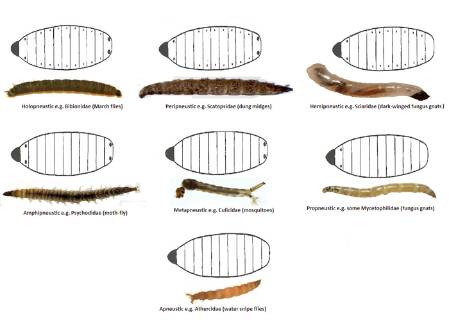

And for such large creatures we know very little about them. This family is considered to be within the infraorder Stratiomyomorpha, but they have not always been positioned here. Originally they were classified within the Tabanidae – the horseflies – and do superficially resemble them (just on steroids) but there are other differences. They were then moved, along with the Xylophagidae, into Xylophagomorpha, but this infraorder is no longer used, with Pantophthalmidae now being subsumed into Stratiomyomorpha leaving Xylophagidae to roam free along the taxonomic highway (Fig.1).

Pantophthalmidae are thought of as being in a relatively stable position snuggled alongside the Stratiomyidae (soldierflies) and Xylomyidae (wood soldierflies). However, I believe some recent work by Keith Bayless of North Carolina State University has now placed the freewheeling Xylophagidae into Tabanomorpha. Everyone up to speed?

Figure 1. Tolweb organisation of Brachycera.

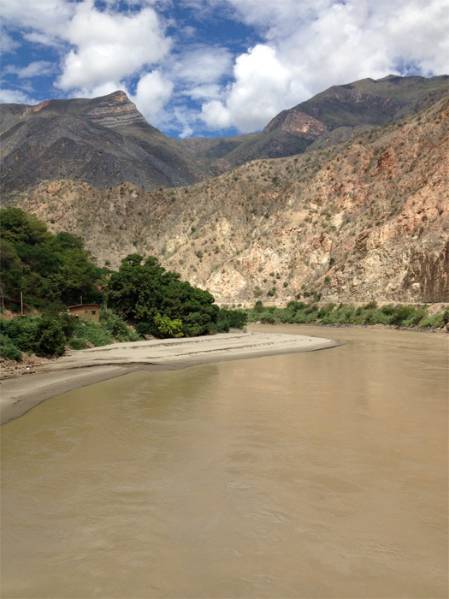

Now we have cleared up the higher taxonomy let's move onto distribution. They have only been found in the Neotropical region from Mexico down through Central America and down through Brazil and Paraguay and across to Venezuela and Columbia. And even though this is a vast area, they are infrequent in most collections.

The key work for this group was undertaken by Val in 1976. He states that these are rare in the collections, but in order to review all of the species and the types, you need to visit 23 different museums (this figure I presume has grown). That is a lot of effort for a handful of species but that would make a great road trip Although our collection goes back hundreds of years we have only 132 pinned specimens but we do have some important type material (Fig. 2). However we are still missing some of the species and one of the genera!

Figure 2. Species in the Museum and whether type material is housed here.

I've always liked this group of flies because they are just so big, and we have actually had some fresh material that comes from some French Guiana material donated to the Museum. It has been sitting there patiently for the last couple of years waiting to be identified and now seemed the ideal time. They had been found by our volunteers, who were surprised by these beasts, as they were so much larger than all the other specimens in the pots.

These flies, as already stated, are big. Pantophthalmus bellardii (bellardi 1862) with its wings spread, can reach 8.5cm in width. Fig.3 gives you an idea of their robust and chunky bodies … we found seven specimens in the donation (of about 50 samples).

Figure 3. One of the glorious specimens - Pantophthalmus bellardii (bellardi 1862).

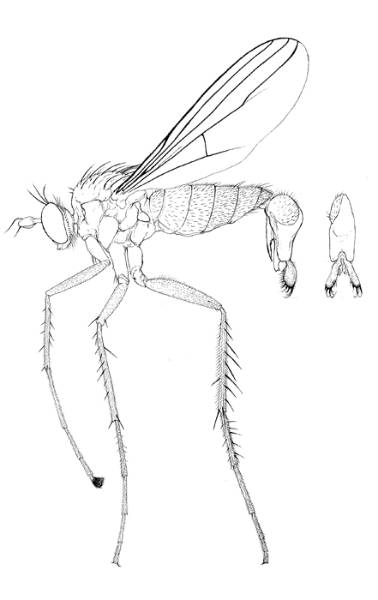

The adults are sexually dimorphic with the males having holoptic heads (all eyeballs!)

Figure 4. The differences between the males and the female heads of Pantophthalmidae.

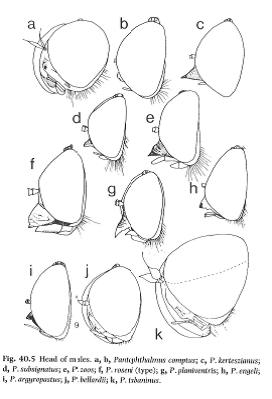

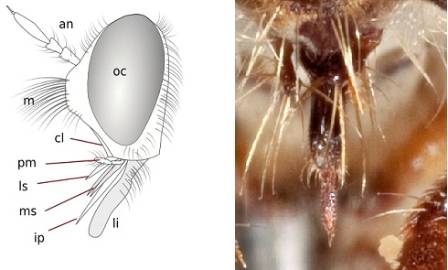

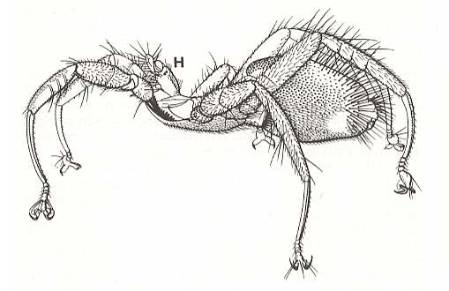

And they have beaks! Actually these are a very useful diagnostic feature…

Figure 5. Beaks of the Pantophthalmidae (from Val 1975).

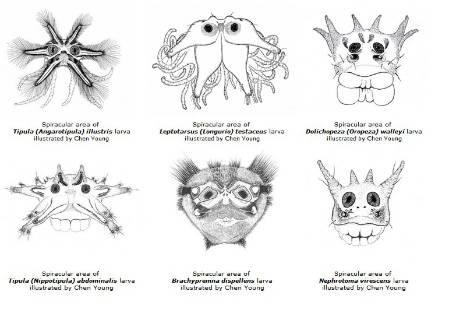

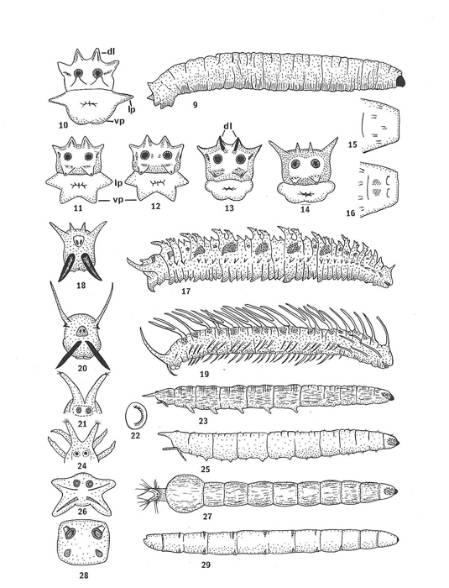

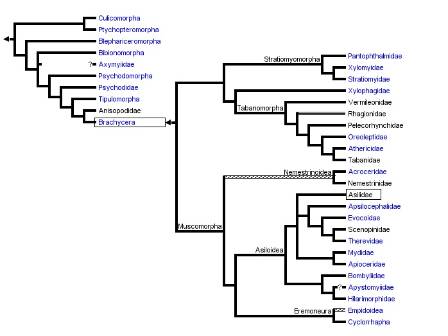

The immature stages are not known from most of the species although we have a range of pinned, dry and spirit material of the larvae. And they too are big, like their mothers and fathers, but we have even fewer of them in the collection (Figure 6 & 7).

Figure 6. Pantophthalmid larvae in relation to adult (abdomen shown).

Figure 7. The Museum spirit collection of Pantophthalmidae.

Why do we only have one jar? One of the problems is that the larvae are wood borers and inhabit galleries that are carved horizontally into the tree – dead or living depending upon the species. We still really don’t know what they are feeding on but many people believe that it could be fermenting sap. Others believe that the diet is a mixture of wood (either dead or in the process of dying) and micro-organisms.

Zumbado writes in his work from 2006 that they seem to prefer mucilaginous trees such as kapok or sap-producing trees such as figs. He goes on to describe how noisy these little critters are – several hundred may be in one trunk and they can be heard munching away from several metres.

The larvae have very robust head capsules and massive mandibles – they are some of the largest larvae I have seen (of all insects). When I read accounts of how many can be seen in one tree, I am quite overcome with envy. We don’t have many in the collection – one jar as shown – but it is a mighty jar. I don’t think I am allowed to say what exactly was said by various colleagues when we brought out some of the specimens but, suffice to say, they were impressed.

This collection was in a sorry state in old drawers and on slats. These are problematic because the pins are so firmly wedged that when you try and remove the pin from the board you often damage the specimens. The specimens themselves were showing some early signs of damage with verdigris on some of the pins (Fig. 8) Verdigris is when the lipids in the insect react with the copper in the pins. Nowadays we use stainless steel pins, so this doesn't happen, but most of the specimens in the collection are mostly older even than me.

Figure 8. Verdigris on pins.

The first thing that I do when I recurate a collection is to find all of the recent as well as the historical literature in catalogues and monographs, and update the database. The Museum database for this family had not been edited for at least 20 years. But luckily, when going through the literature, I discovered that with this family, not a lot had happened in that time. But our records were still inaccurate, and for a family with very few species people kept changing their mind about the number of genera and where the different species sat. Sorting that out took the most time in terms of overall curation, as there were so many new combinations and I had to be certain of all the taxonomic rearrangements. You should have heard my sighing as I was typing in the data (I promise it was just sighing).

Remember that there were only 20 described species of which we had (past tense is important here and I’ll come back to that) only 15? Well, the number of taxonomic records we now have in the database of all the original combinations and numerous synonyms (the many, many synonyms) is about three times as many as the actual number of species (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Taxonomic names for genera and species.

Once this was sorted out, I started on the production of the labels. I have to produce an initial first draft of the list of species names (Fig. 10) as I need to ascertain where and what all of the types were, as well as how many unit trays of each size are needed. I have many lists scattered around my desk so one more can’t hurt…

Figure 10. Lovely lists of the species of Pantophthalmidae in the Natural History Museum Collection.

N.B. See – hardly any valid species names without synonyms!

Next I needed to make my unit trays up. My lists have codes on them indicating what the type was and how many of which size trays – there is an awful lot of organising with curation and it definitely fulfils my OCD tendencies…We have three sizes of unit trays that we use for Diptera recuration but somehow I knew that I probably wouldn’t be needing any of the very small A trays (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Unit trays –C, B and A.

N.B ok that is quite a nerdy photograph!

The new sparkly labels (ok the sparkly bit is a lie) were placed into the unit trays and then I started transferring the material across. As the specimens were moved they were inspected for damage – any verdigris removed and any legs etc. placed into gelatine capsules. Three new main drawers later and the collection was now housed in museum-standard drawers, conservation-grade trays and labels, completely updated on the database and new material incorporated into it (Fig. 12).

Figure 12. The largest smallest recuration project.

So let’s go back to this new material consisting of just a few specimens. Not a lot you may think – but remember this collection is not very big. For large flies, they were slightly difficult to ID. In fact, as the samples had come out of the window traps (the specimens collect in alcohol) they were very greasy.

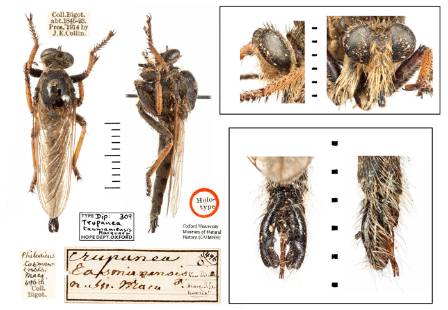

Chris Raper, a fellow Dipterist at the Museum and lover of these flies, suggested that I give them a bath in ethyl acetate. I was a little nervous about leaving these precise specimens overnight in this rather noxious fluid. But lo and behold! What wonders were to great me the next day! Wonderful, they were – just wonderful. And suddenly we were able to see features that were previously hidden, such as thoracic patterns and, rather more importantly, hairs on the eyeballs. This feature alone split the two different genera and so we realised that for the first time, our collection now has ONE Opetiops alienus (Fig. 13). I believe this is also the first time that it has been collected from French Guiana.

Figure 13. Opetiops alienus – check out not only the hairy eyeballs but also the beak!

So one database updated, one collection rehoused and once more new material has been added to the collection. Happiness reigns in the Land of the Curator.

.jpg)

.jpg)