Recently, I have been quiet in the land of blogs but fear not - this was not due to the lack of things fly-related but rather the opposite. I have been working on a three-part BBC Radio 4 series on all things funky about insects and what we can learn from them - not just on a taxonomic or ecological scale but also thinking about their adaptions and functionality, and how we can utilise this.

Over the last month or so, I have possibly had the most fun an entomologist can have without a net and a few million dead flies. I was approached a while back by Laura Thomas, a BBC radio producer, about presenting a three-part series on insects that would involve me interviewing some of the most innovative individuals whose work focuses on many different aspects of insect ‘technology’ (I use that term loosely) ...

And so I have dangled from a ceiling, played with spiders, eaten bees, admired bot flies, and seen entomo-bots, to name just a few things. And it’s been amazing. I have probably said “that’s marvellous” more than any other phrase, and have wound up all those around me with astonishing facts - I am a pub quiz waiting to happen; my brain is full of wonder and awe. Anyone who does not love insects does not love life!

OK, so to my first story from the series … sniffer bees. I was possibly most excited about this out of all of my encounters (however, next week I will say the same about the story I'll cover then, and then the same the week after). These amazing creatures are actually your bog-standard honey bees - making honey and saving us as part of their daily routine!

An amazing honey bee, Apis mellifera

And I am not alone in thinking that they are amazing - sniffer bees have caught a lot of other people's imagination:

So, my producer and I headed out of London one cold day to visit Inscentinel, based in Harpenden, Herts. In one innocuous-looking building, up a flight of stairs and round the corner in a small lab, all the action happens. There are two fume hoods, both being used by people wafting chemicals to bees in pods. And to talk me through everything was Dr Maxim Rooth. Now his biog tells us that he is not an entomologist - far from it:

‘Dr Maxim Rooth has a BSc in biological and medicinal chemistry and an MSc in biological chemistry. He went on to specialise in optical biosensors … and completed his PhD in chemistry at Exeter University. He has a thorough knowledge of biosensors, surface chemistry, colloid chemistry and bio-conjugation.’

So what is it about his background that makes him so useful? It is his knowledge of biosensors that is the key. Maxim's group use the bees' natural responses to certain stimuli and, by using optical biosensors, they have developed a machine that is capable of detecting chemicals to help us in locating - among other things - bombs and drugs! Way to go bees.

For years we have been using bees in warfare: hurling nests of angry bees about. We have chucked them across the water at opposing ships and launched them on specially developed trebuchets. But recently we have started to think about how to use them to assist us in ways other than warfare, such as detection of drugs, and even more cunningly in detecting illnesses within humans.

Previous studies have used bees and their famous waggle dance to determine the position of land mines ... have I said it yet, what marvellous little creatures. For example, the BBC have already covered a story of work conducted by Professor Nikola Kezic, about the use of this technology to find land mines in Croatia. Sandia, University of Montana is another making use of bees in this way. This research is happening all over the planet - and quite rightly so as land mines are still a huge problem (the Red Cross states that there are 45 to a 100 million land mines still active).

So how does this work? You make a concoction of a sugar solution containing the chemical (in this case TNT - or one of the smelly components of it; I am very technical!). You then feed this to the bee! Different studies use different methods to do this. This is an image from the Sandia group where they have made up pots of the solution. The bees in this instance feed on the sugary solution and then head off into the wilderness:

Feeding bees chemical-laced sugar solution

You can either spot the bees that have detected land mines with some binoculars(!) or you can develop highly sophisticated sensory devices to do the same ... I think you can probably guess which technique is the favoured one. Inscentinel have used this idea of chemical detection and taken it a step further ... bees have tongues, and long ones at that:

Bees have a long tongue relative to their body size

What happens when you feed them a solution with the chemical of choice is that, when they then come across the chemical again, they stick their tongues out! “Marvellous”, I hear you cry (I almost did when they let me feed one to see this in action). And they respond this way because they associate the chemical with the sugar solution upon which they have been fed.

Now, in the past, we have used sniffer dogs and they are very effective, but dogs are expensive and take a long time to train ... and then retrain, because they eventually forget. Bees on the other hand take about 5 seconds to train (to be sure though, they repeat the training six times and then they give them a dummy test). In a Naked Scientist article on sniffer bees, research scientist Dr Nesbit says:

“Bees are at least as good as sniffer dogs but are cheaper and faster to train, and available in much larger numbers ... Bees can detect some odours that are present in parts per trillion - that’s equivalent to detecting a grain of salt in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.”

Just as Pavlov's dogs salivated at the sound of a bell due to their associating it with food, when the bees next smell the target chemical they automatically stick out their tongue as they believe that food will appear. And, unlike sniffer dogs, bees cannot help but do this time and time again as it is an innate response - dogs often get bored and forget they are being employed on top military assignments!

For the sniffer machine, each bee is placed in a little pod (they are put in a fridge first to make them dozy!). Then they place the suspect solution on their antenna, where chemoreceptors cause a Pavlovian response if it contains the target chemical.

One of Pavlov’s actual dogs is now a museum specimen! Though, sadly, not one of ours.

One of Pavlov’s actual dogs is now a museum specimen! Though, sadly, not one of ours.

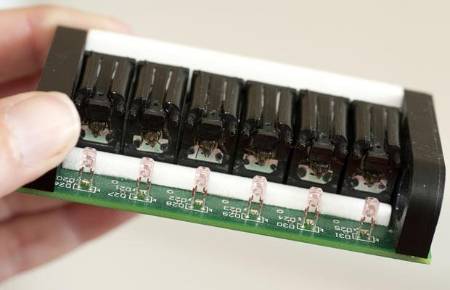

And how does this relate to Maxim and his knowledge of biosensors? Well when the bees stick their tongues out, it passes through an infrared beam thus disrupting it. When all the bees are doing this (there are 36 in the machine) at once we can be pretty confident that the chemical is present.

Bees lined up in their pods and ready for action!

The hand held sniffing machine!

Such a simple and inexpensive idea, showing us once more that nature is very clever! P.S. I want one of these machines...