So Last week I performed a HUGE 9 minute set for a Museums show off. People from all over the museums and libraries sector come and present a skit on something about their work or their museum. Now I choose to highlight the wonderful creatures that are maggots. They are all over my desk, I get sent them in the post, yesterday I, alongside a colleague, were hunting for them in the wildlife garden, I was rearing them from poo in the towers – in fact, maggots are very dominating in my job. And quite rightly so.

So I thought that I would convert that into a blog about these fantastic things and why the collections and the staff at the Natural History Museum are so important with maggot research! I have briefly touched upon maggots before but i thought that I would go into some more detail.

Let’s first clarify what a maggot is. The term maggot is not really a technical term and if you type in ‘what is a maggot’ on Google you get this!

To this date I have never heard someone describe something they yearn for as a maggot but who can say what will happen tomorrow with language fashions.

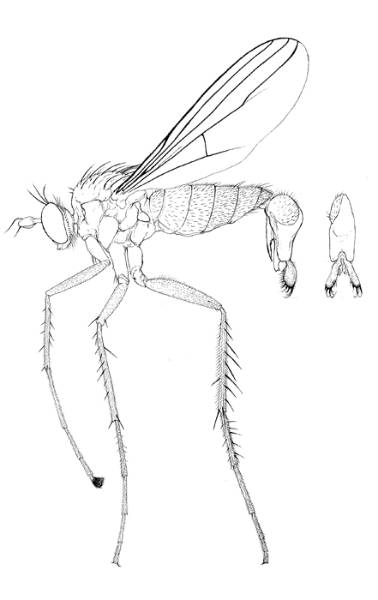

The maggot is a juvenile or, as I prefer to call it, the immature stage of a fly. These vary in form across the order from the primitive groups of flies (Nematocerans) to the more advanced groups (Brachycerans). The primitive groups have a more defined form in having a distinct head capsule with chewing mouthparts and we refer to these as Culiciform (gnat shaped).

A mosquito larva which is culiform (gnat shaped).

A mosquito larva which is culiform (gnat shaped).

Those more advanced flies whose larvae are without a head capsule and mouth parts that have just been reduced to hooks are called Vermiform (literally meaning worm shaped); and it is the later group that we generally call maggots!

A slightly more informative picture of some Vermiform larvae - the maggots of a blowfly.

A slightly more informative picture of some Vermiform larvae - the maggots of a blowfly.

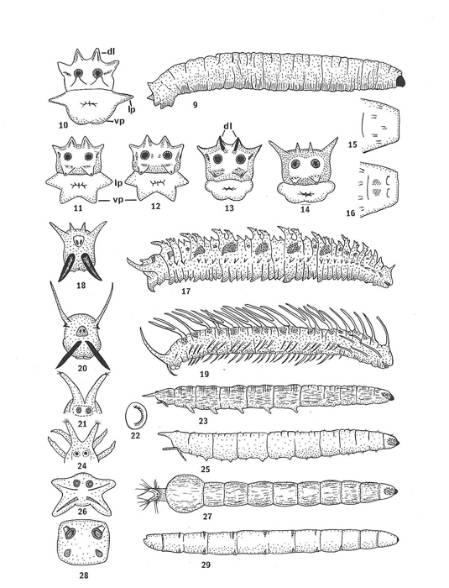

We can label describe these head capsules further into three types;

- Eucephalic (distinct capsule and mandibles)

- Hemicephalic (incomplete capsule and partly retractable mandibles)

- Acephalic (no distinct capsule with mouthparts forming a cephalopharyngeal skeleton)

A trichoceridae larvae (eucephalic) © Matt Bertone.

A trichoceridae larvae (eucephalic) © Matt Bertone.

An Atherceridae larvae (Hemicephalic).

An Atherceridae larvae (Hemicephalic).

And a housefly maggot (Acephalic larvae).

However for the purpose of this blog I will use the term maggots to include all Dipteran Larvae as there are some very important (and incredibly attractive) larvae from some of the more primitive groups. And they differ from most other insect larvae by the lack of jointed legs on their thorax. Beetles larvae are grubs, Butterflies and moths are caterpillars, bugs just have mini-versions of the adults, but they all have jointed limbs.

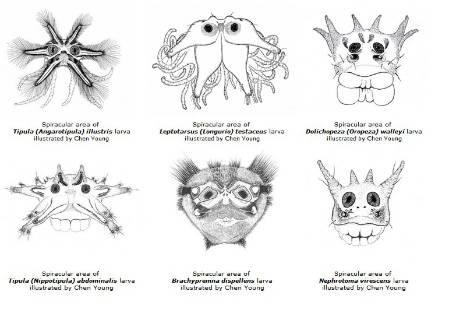

Above are some of the more incredible images of a cranefly larva. But these are not the heads of the cranefly larvae but rather their anal or posterior spiracles (breathing tubes). Anytime I need cheering up I flick through images of posterior spiracles.

Above are some of the more incredible images of a cranefly larva. But these are not the heads of the cranefly larvae but rather their anal or posterior spiracles (breathing tubes). Anytime I need cheering up I flick through images of posterior spiracles.

Most people just view the larvae from either above or parallel but these are from bottom on! (these above diagrams are from the brilliant book by Kenneth Smith on Identification of British Insects) but as you can see some of the more interesting features are from this angle.

Most people just view the larvae from either above or parallel but these are from bottom on! (these above diagrams are from the brilliant book by Kenneth Smith on Identification of British Insects) but as you can see some of the more interesting features are from this angle.

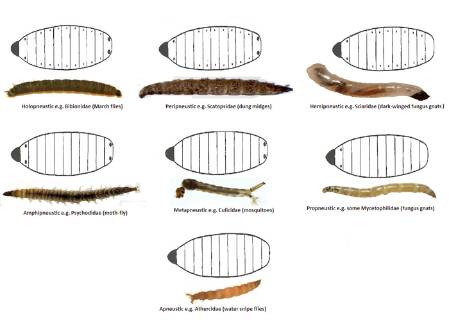

These spiracles form part of a breathing system that enables the maggot to breathe whilst feeding. These vary across the fly group with there being 7 different set ups of the spiracles.

Location of spiracles on the body of a maggot, shown with dots and circles.

Location of spiracles on the body of a maggot, shown with dots and circles.

The above diagram from top left to bottom middle shows (by dots and circles) where the spiracles are on the body. Some systems are very common such as the amphinuestic set up being found in most Diptera whilst others are very specialised such as the proneustic systems (only found in some fungus gnats). Some of them have taken their spiracle and run with it (as it were). Check out the rat-tailed maggot below (larvae of a hoverfly).

Rat-tailed maggot (larvae of a hoverfly).

The mouth can concentrate on ingesting food solidly – just imagine 24/7 eating. Now the maggot stage is the one designed for eating. I often wonder what it would be like to have the lifestyle of a fly – born, eat, eat, eat, eat, eat, mate, die…..and therefore they don’t have to have all of the equipment of the adult.

As I have already mentioned the larvae of Diptera do not have legs as other groups do such as the moths or the ants. This is because they are highly specialised examples of precocious larvae i.e. examples of very early hatching. And this is what arguably has lead to the most diverse range of habitat exploitation of all insects. They are plastic; they can squeeze themselves into tiny holes and between surfaces and therefore take advantage of so many different food sources.

In the wonderful book by Harold Oldroyd – The Natural History of flies - there is a sentence that states that the larva and adult are more different from each other than many Orders of Insects. And so in many ways with many species you could argue that flies fit two lifetimes into one as they are often completely different, both in form but also in diet and habitat.

Maggoty enquiries

The Diptera team have been talking maggots a lot recently. One of us, Nigel Wyatt, is something of an expert already on most things maggoty, working on most commercial, consultancy and public queries relating to maggots.

I had one recently from a friend of mine. She is a vet and one of her colleagues works with Police Dogs. Her colleague was a little confused and concerned about a maggot that was defecated by one of the dogs as she had not seen one so large before. My friend immediately thought of me and sent it to the Museum in a little tube of alcohol. Despite the alcohol it was quite fragrant by the time it arrived on my desk but it was easily identifiable as a cranefly larvae. Now cranefly larvae are incredibly versatile in terms of their habitat – they live in moss, swamps, ponds, decaying wood, streams and soil but as I far as I know the inside of a dogs alimentary canal is not a known habitat. They consume algae, microflora, and living or decomposing plant matter, including wood and some are predatory but parasites they are not. This one had miraculously come through the entire digestive tract of a dog without being destroyed. No harm done except to ones nasal cavities.

However, cranefly larvae or leatherjackets as they are sometimes called have caused some problems to lawns due to them consuming grass roots. Wikipedia – the great font of scientific knowledge cites from Ward’s Cricket's Strangest Matches ‘In 1935, Lord's Cricket Ground in London was among venues affected by leatherjackets. Several thousand were collected by ground staff and burned, because they caused bald patches on the wicket and the pitch took unaccustomed spin for much of the season.’

Apart from the staff who help with identifications we are helping further with outreach by helping with development of a new, hotly awaited book on British Craneflies. Alan Stubbs (not the retired footballer but the rather more impressive Dipterist and all round Natural History Good Egg) and John Krammer (retired teacher and superb Cranefly specialist) have been working on this fantastic tome for a while now and we have all been trying and re-trying the keys to ensure that they work. Preparations of gentailia, wings and larvae have been undertaken at the Museum on both Museum specimens and ones donated by John, and images and drawings of these been done. Carim Nahaboo has been drafted in for some of the drawings so expect great things.

This is an adult Dolichopodidae but it is a fine example of Carim Nahaboo's artwork.

Flies and their offspring have a terrible reputation. People are disgusted by most of them. However, they are essential both for our health and habitat but also for telling us what is happening.

Dr Steve Brooks and his group at the Museum work on Chironomidae (non-biting midges), and more specifically the immature stages – their larvae. Chironomid larvae are quite primitive and as such have a complete head capsule which is … as the larval stages develop they shed their head capsules and grow new ones, and these discarded ones can be used to determine the environmental conditions of the habitat both now and in the past as well as monitoring heavy metals.

Head capsule of a chironomid, which can be used to determine past environmental conditions.

I first came to the Museum as a professional grown up thanks to Steve as I was conducting a study using Chironomids as indicators of environmental health as they are fantastic bioindicators. Many Chironomid species can tolerate very anoxic environments as they, unlike most insects, have a haemoglobin analog which is able to absorb a greater amount of oxygen from the surrounding water body. This often gives the larvae a deep red colour which is why they are often called blood worms. Although slightly fiddly as you have to dissolve the body in acid, the use of head capsules for identification (image above) is fairly straight forward. The little crown like structures that you can see are actually rows of teeth and these are very good diagnostic features. Steve has worked for a long time on the taxonomy of these species and his (and his groups) expertise has been used globally.

So as well as looking funky we can use them to tell us many things about the world of today and yesterday. More on maggots in the future.