A new relative of lizards has been named from fossils separated for almost a century.

Now called Sphenodraco scandentis, the ancient reptile is the oldest of its kind known to have climbed among the trees in ancient Jurassic forests.

Rhynchocephalians like Sphenodraco scandentis were at their peak during the era of the dinosaurs. © Gabriel Ugueto

A new relative of lizards has been named from fossils separated for almost a century.

Now called Sphenodraco scandentis, the ancient reptile is the oldest of its kind known to have climbed among the trees in ancient Jurassic forests.

A new species of ancient lizard-like reptile has been described after a link between two fossils in different museums was rediscovered.

When PhD student Victor Beccari was studying the fossil reptiles cared for by the Natural History Museum, he was surprised to see a very familiar-looking skeleton. It looked incredibly similar to another fossil he knew about in the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, of a lizard-like animal known as a rhynchocephalian.

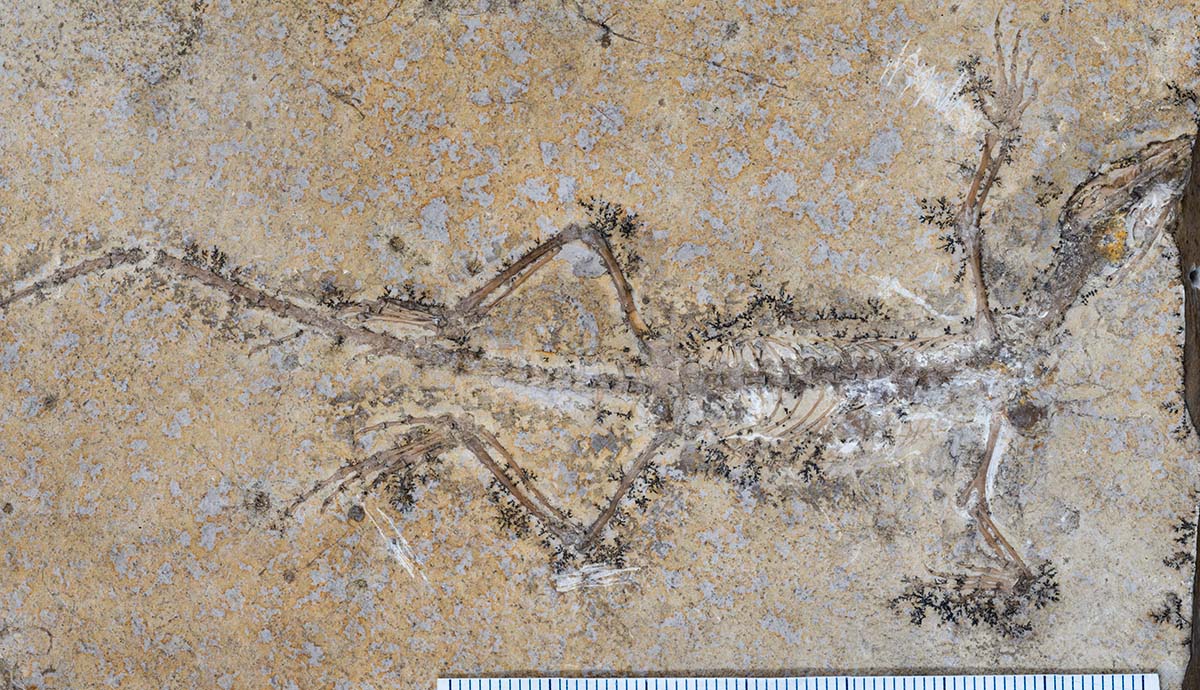

The fossil in Frankfurt preserved the reptile’s outline, while the one in London contains many more bones. Further study revealed that these fossils weren’t just similar – in fact, they were two halves of the same fossil.

“These kinds of fossils are normally preserved flat, so when they’re split open you often get the skeleton in one half and the impression of the skeleton in the other,” Victor says. “However, it’s unusual to find two halves of a fossil in different museums.”

“It seems that someone in the 1930s decided to double their profit by selling both halves separately. As they didn’t tell either buyer that there was another half, the connection between the two fossils had been lost until now.”

While the Senckenberg fossil had been identified as Homoeosaurus maximiliani, the details preserved across both fossils suggest that’s not the case. In fact, Victor and a team of scientists concluded that the animal is new to science. The new species, Sphenodraco scandentis, appears to be the earliest tree-living rhynchocephalian ever discovered.

The findings of the study, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, reveal more about the wildlife of the Late Jurassic over 145 million years ago.

The Senckenberg fossil mainly preserves an impression of the outline of the animal's skeleton. © Victor Beccari

Rhynchocephalians look like lizards but come from a completely separate part of the reptile family tree. Today, the only living rhynchocephalian is the tuatara from New Zealand, but in the past these animals were just as widespread as modern lizards.

The rhynchocephalians reached their peak diversity during the Mesozoic, the Era containing the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. While the dinosaurs became the planet’s dominant large animals, rhynchocephalians would have made up a significant amount of the small animals running between their feet.

One of the key places on Earth for studying rhynchocephalians is an area of German rocks known as the Solnhofen Limestone. During the Late Jurassic, this region would have been a chain of islands across a subtropical sea.

While Solnhofen Limestone is better known for fossils of species like Archaeopteryx, it is also where the first rhynchocephalian fossils were found almost 200 years ago.

“Solnhofen fossils are famous for their exceptional preservation,” Victor says. “We know that all the sediment is marine, and so it seems that animals living around these islands ended up being swept out into some oxygen-poor areas when they died.”

“This would have kept scavengers away from them and allowed their soft tissues to survive, meaning that the fossils preserve a lot more than you might expect.”

The Natural History Museum fossil contains the majority of Sphenodraco’s bones, allowing insights to be made about its lifestyle. © Victor Beccari

Although the fossils are well-preserved, they’ve not all been studied in detail. Many of the historic descriptions of rhynchocephalians are somewhat vague, focusing on characteristics that are fairly broad across a variety of animals.

“I think we’re really underestimating the diversity of these animals,” Victor adds. “In a lot of cases, fossils coming from the same place that look somewhat similar get lumped together. So, everything with longer limbs was called Homoeosaurus and everything with shorter limbs was Kallimodon.”

“The closer you look at how these animals have been studied in the past, the more you appreciate that the species aren’t that well-defined. We know that modern islands can have hundreds of species of reptiles, so there’s no reason that ancient islands didn’t too.”

“Although Solnhofen has provided many beautiful complete skeletons of rhynchocephalians, their skulls are sometimes crushed or part of the skeleton are still buried in the rock,” adds co-author Dr Marc Jones. “This has meant that, until recently, the Solnhofen material hasn’t contributed to our understanding as much as it should have.”

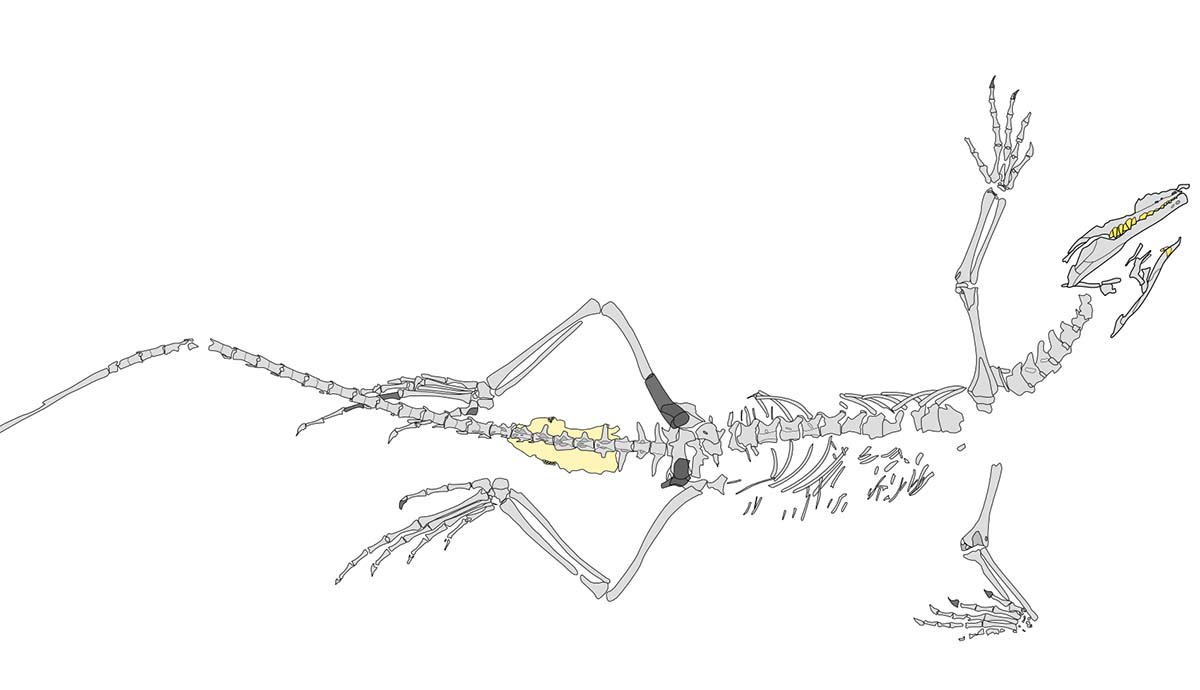

As the team investigated the Senckenberg and Natural History Museum fossils carefully, they noticed that certain bones didn’t fit with its description. Its teeth were in a different orientation to Homoeosaurus’s, while the hip bones had a different structure.

This led the researchers to name the fossils as the new species Sphenodraco scandentis. But the new species still had more to reveal.

The long finger bones of Sphenodraco suggest that it probably climbed trees. © Victor Beccari

Historically, research into the lifestyle of rhynchocephalians has focused on what they ate by examining their teeth and jaws. Victor, however, is taking a detailed look at the rest of their bodies to get a broader insight into the animals’ lifestyles.

As only the ground-living tuatara survives today, Victor has had to compare fossil rhynchocephalian skeletons to their closest living relatives instead.

“By measuring the size of their body and limb proportions, we can then compare them to living lizards with known lifestyles,” Victor explains. “This allows us to infer what rhynchocephalians might have been doing in the Jurassic.”

The varying body sizes of extinct rhynchocephalians show that different species had a range of different lifestyles. Animals like Pleurosaurus had long bodies with long back legs and short front limbs, so they are thought to have been fully marine. Other species had long limbs good for running, while those with a shorter body were probably climbers.

The newly named Sphenodraco is most similar to the latter group, but its long limbs and short body don’t necessarily indicate what it was climbing.

Closer examination of its long finger bones shows similarities with modern gliding lizards, suggesting it probably spent its life in the trees. This would make it the oldest known arboreal rhynchocephalian discovered so far.

“I’m going back over existing fossils to look for signs that other currently accepted species might cover multiple rhynchocephalians,” Victor says. “There are also still a number of undescribed specimens that may also represent new species as well.”

“It goes to show just how important museum collections are to understanding ancient diversity. Even though many of these fossils were discovered almost two centuries ago, there’s still a lot they can teach us.”

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media