Amphibians the size of crocodiles once lurked along the shores of ancient South Africa.

Newly described fossils reveal how these animals moved in the water as they looked for prey during the Permian.

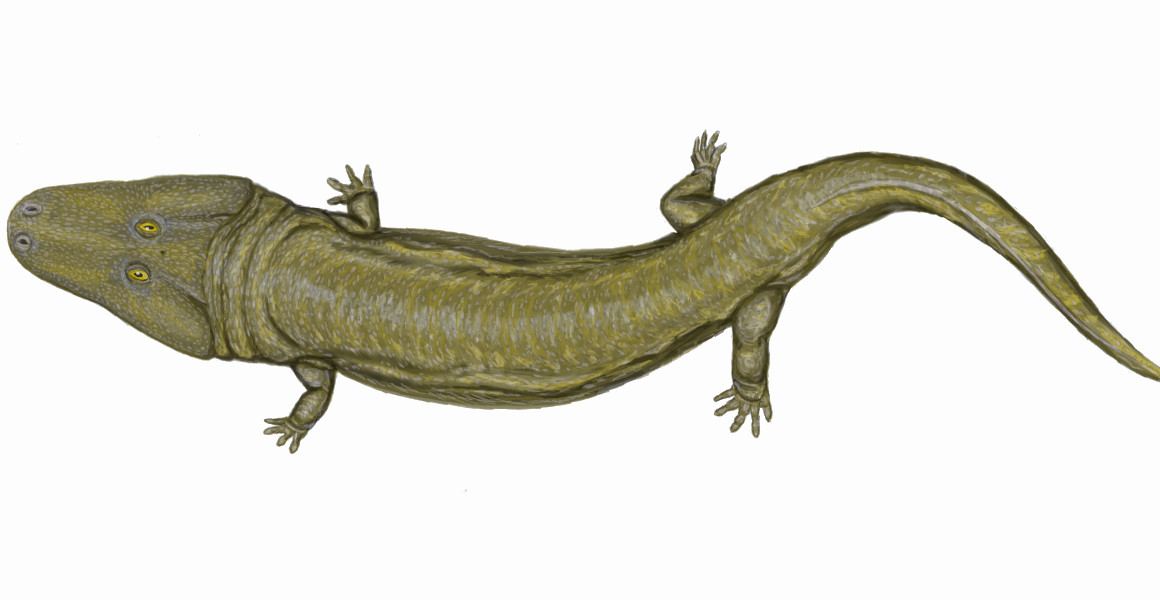

The tracks may have been made by a giant temnospondyl like Uranocentrodon senekalensis. Image © Dmitry Bogdanov, licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Amphibians the size of crocodiles once lurked along the shores of ancient South Africa.

Newly described fossils reveal how these animals moved in the water as they looked for prey during the Permian.

Over 250 million years ago, giant amphibians would have roamed the edges of ancient lagoons.

Fossils uncovered in South Africa preserve the tracks left behind by salamander-like animals known as temnospondyls. They reveal that these amphibians moved much the same as crocodiles do today, sweeping their tails from side to side to push themselves through the water.

The tracks also show that these amphibians were part of a wider Permian ecosystem containing tusked mammal relatives, known as dicynodonts, as well as a range of fish, invertebrates and plants.

Dr David Groenewald, the study's lead author, says. 'The trackways are unique, and as far as I know, the only Permian body impressions of a rhinesuchid amphibian of this size.'

'While it has been suspected that these animals swam similarly to modern salamanders and crocodiles, it was neat to find direct evidence in the fossil record.'

The paper was co-authored by Dr Mike Day, Curator of Non-Mammalian Tetrapods at the Museum, and published in the journal PLOS One.

The Dave Green palaeosurface preserves the floor of a tidal flat or lagoon on the edge of the Karoo Sea. Image © A. Krüger

Rocks of the Karoo supergroup are found across much of southern Africa, reaching as far east as Madagascar and as far north as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and southern Kenya. The tracks were found in the main basin, which covers a large part of South Africa and Lesotho.

While the rocks span a period of over 150 million years from the Carboniferous to the Jurassic, they are particularly useful for studying a time known as the Permian. This period is important to study as many major animal groups, such as sharks and tortoises, first became prominent at this time.

During the Permian, the Karoo was thought to be a large, shallow sea surrounded by rivers and lagoons, with the soft sediment helping to preserve the body fossils of a wide range of animals. But the sediment also lends itself to preserving trace fossils, which capture aspects of an animal's behaviour.

The fossils in the current study were discovered at the Dave Green palaeosurface, named after the landowner who brought it to the attention of researchers in the 1990s. They are a series of impressions left behind by the feet, fins, bellies and tails of ancient animals.

For instance, small fossils forming grooves are believed to have been left behind by the fins of ancient fish as they were dragged along the sand while swimming. Meanwhile, small footprints are believed to have been left by dicynodonts, whose footprints have been found elsewhere in the Karoo basin.

However, it is the larger impressions that have caught the attention of the scientists. Forming two almost circular routes, they are believed to represent the path taken by one or two temnospondyls over 250 million years ago.

'Unlike other fossil trackways, it's not the footprints that stand out, but the tail and body impressions instead,' David explains. 'These are larger than many other fossil amphibian body impressions, which are often less than 30 centimetres long.'

Temnospondyls were a group of early amphibians, first evolving around 330 million years ago and existing for over 200 million years. Though it's still uncertain, some studies suggest that they are the ancestors of modern frogs and salamanders, which if true would mean the temnospondyls still exist today.

They had a wide range of sizes, with species such as Uranocentrodon senekalensis able to grow up to four metres long. Some large temnospondyls would have played a role similar to crocodiles in their ecosystems, acting as semi-aquatic carnivores around ancient waterways.

As a result, the temnospondyl traces look similar to the tracks of modern crocodiles and alligators, even though the ancestors of these reptiles wouldn't evolve until millions of years later. The fossils preserve an outline of the body and tail, which has been used by the researchers to estimate an overall length for the animal of around 1.9 metres.

This size suggests that Uranocentrodon, or another temnospondyl like Laccosaurus, might have been the trackmaker, but without body fossils it's impossible to be certain. However, the tracks do reveal how these animals might have moved.

'When looking at other fossil trackways, or modern crocodile drag marks on tidal flats, the footprints are normally the thing that stands out,' David says. 'However, only one of the seven impressions at this site is associated with footprints, so we argue that these traces are evidence of swimming.'

Other evidence cited by the researchers are bulges near to the tail in the impressions, which have been interpreted as the animals tucking their back legs in while swimming. Meanwhile, the fossils also show an s-shaped pattern which suggests they were using strokes of the tail to propel themselves forward.

Both of these behaviours are seen in modern crocodiles and salamanders, which can also walk along the floor underwater. This behaviour, known as bottom walking, is also preserved with tracks extending across the Dave Green paleosurface.

The team continue to look for more well-preserved sites, hoping to find out more about the lives of animals millions of years ago.

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media