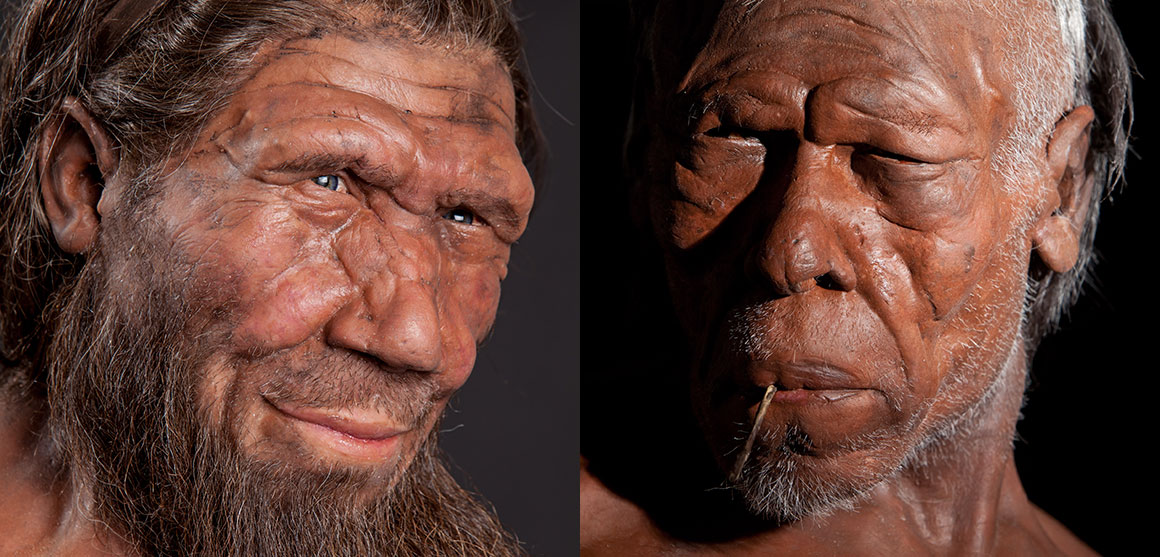

Study reveals how Neanderthal faces changed throughout their lives to develop their characteristic protruding shape. Compared to the rest of the human family tree, it turns out that we - Homo sapiens - are the unusual ones.

Neanderthals' upper jawbones continued growing forwards for years after they were born, explaining the distinctive protruding face shape of this extinct human species.

Unlike modern humans, whose faces remain flat as they grow, Neanderthals had cells in their upper jawbones that continued producing bone tissue throughout their teenage years.

Because other ancient humans and early relatives like the australopithecines (southern apes) had a similarly protruding face, our flatter faces are unique among human species and may have emerged only very recently.

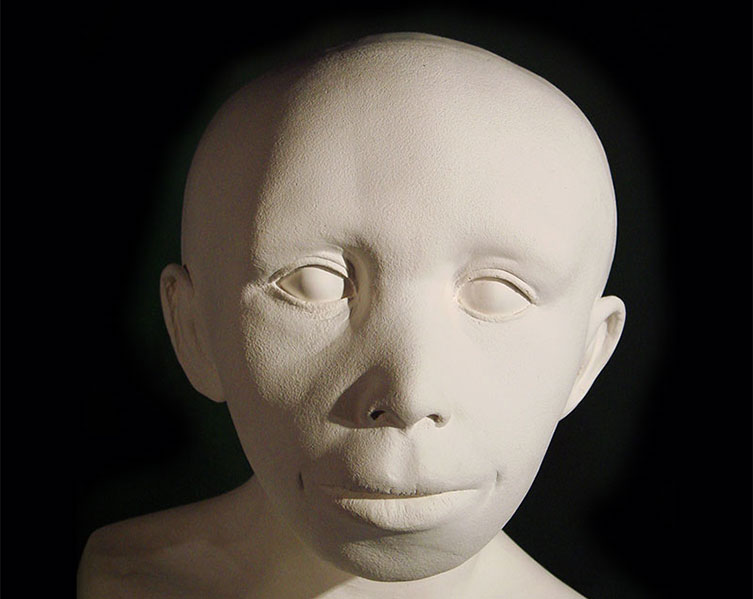

The five Neanderthal child skull fragments found at Devil's Tower in Gibraltar in 1926

Devil's Tower specimen

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications today, focused on the upper jawbone of a Neanderthal child who was just under five years old at the time of death.

The fossil was found in 1926 alongside four other skull fragments from the same child at a site in Gibraltar called Devil's Tower, and is now part of the Museum's collection.

'The Devil's Tower child died close to five years of age and this difference in facial growth from modern humans was already apparent by then,' says Museum human origins expert Professor Chris Stringer, who was part of the international team of researchers studying the fossils.

'This research shows how fossils found 90 years ago can still provide crucial information on human evolution through new investigative techniques.'

Reconstruction of the Devil's Tower Neanderthal child's face. By Guérin Nicolas (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Nature's nip and tuck

The different face shapes of apes, ancient humans and modern humans are in part a result of the ways skulls grow and develop after birth - a process known as bone remodelling.

In modern humans, this process sees bone tissue predominantly added to the upper parts of the face (the nose and forehead) and removed from the lower-middle area (especially the upper jawbone). This leaves us with a flatter face in adulthood.

Using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers found that the Neanderthal child from Gibraltar had many active cells responsible for building bone tissue (osteoblasts) in the upper jawbone, but no active cells responsible for breaking bone tissue down (osteoclasts).

This implies that the characteristic protruding upper jaw of Neanderthals was the result of extensive bone remodelling after birth - the exact opposite of modern humans, where bone remodelling results in a less prominent upper jaw.

Cellular analysis of the skulls of Neanderthals and the Sima de los Huesos hominins. Purple indicates the presence of cells for bone growth (deposition), and turquoise indicates cells for bone removal (resorption). © RS Lacruz, TG Bromage, P O'Higgins, JL Arsuaga, C Stringer, R Godinho, J Warshaw, I Martínez, A Gracia-Tellez, JM Bermúdez de Castro and E Carbonell

A recent twist

The team found similar results in other Neanderthal fossils, as well as in a group of approximately 430,000-year-old hominins from Sima de Los Huesos in Spain who are thought to be ancestors of Neanderthals.

Given that most known species of ancient hominin had a similarly protruding face, the flatter shape of modern humans must have emerged only recently in our evolutionary history.

The researchers say that pinning down exactly when, where and why this happened should be the focus of future work.

'Our study shows that the faces of Neanderthals and modern humans differed in key developmental processes, allowing us to understand how some Neanderthal traits came about,' says co-author Dr Rodrigo Lacruz of New York University.

'In a sense, the Neanderthals are not a developmental oddity - we are.'

Human Evolution gallery

The Devil's Tower young Neanderthal specimen that informed this research is on display in the Museum's Human Evolution gallery. Read the gallery news.

Related information

- Read the scientific paper on the Nature Communications website

- Find out more about the Museum's research on vertebrate and anthropology palaeobiology

- News: Neanderthals and humans had ample time for interbreeding

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media