Trilobites withstood events that shaped our world for more than 250 million years, enduring continents shifting, ice ages, mass extinctions and the evolution of fierce predators.

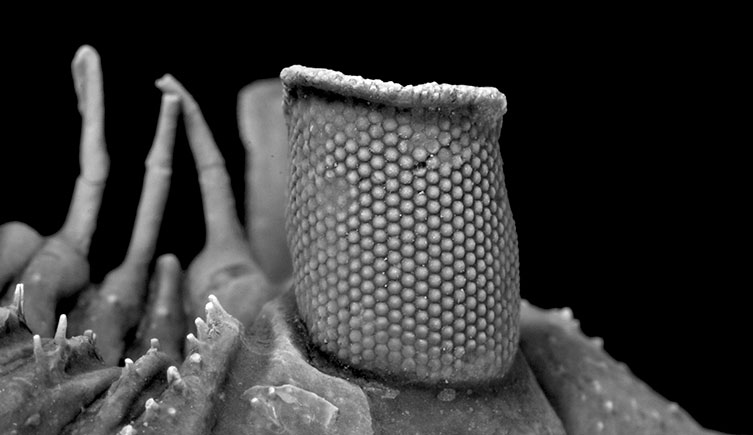

Trilobites surveyed the world through unique crystal eyes that took a variety of forms, such as the tower-like eye structures of Erbenochile erbeni.

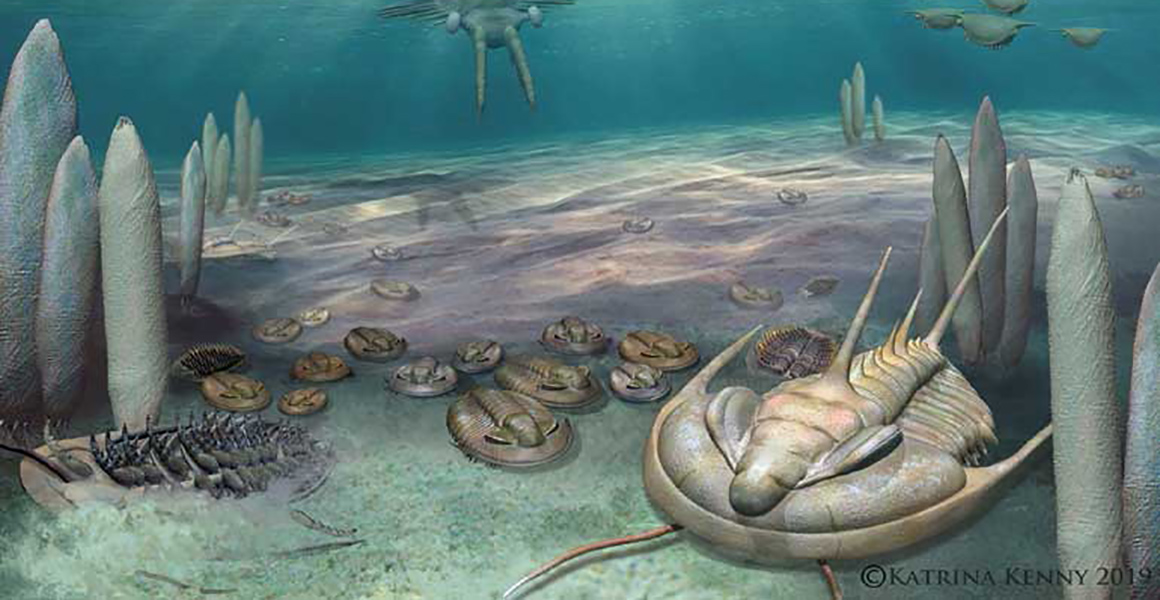

After suddenly appearing in the Cambrian Period, trilobites diverged into thousands of species that lived throughout Earth’s oceans during the Palaeozoic Era. Discover what made trilobites some of the most successful early animals.

What is a trilobite?

Trilobites were marine animals and part of a group known as arthropods. Arthropoda is the largest phylum of invertebrate animals and includes several groups you may recognise such as insects, spiders and crustaceans.

What we know about trilobites comes from fossils. Their preserved exoskeletons show us that their appearances were strikingly varied. As our Scientific Associate Professor Richard Fortey puts it in his book Trilobite! Eyewitness to Evolution, ‘there were trilobites as spiky as porcupines and as smooth as boiled eggs; trilobites larger than lobsters and smaller than gnats’.

Despite this diversity, underneath it all trilobites actually stuck to a very particular blueprint.

The word trilobite means ‘three lobes’. All trilobites had a head known as the cephalon, a tail called a pygidium and a thorax between them. Their thorax was divided into segments, with different species having a different number of segments. These thorax segments could bend at the joints, allowing the trilobite to curl up into a ball, a bit like a woodlouse. Their tails also had segments but these were fused together.

But their bodies weren’t just divided into three segments from head to tail, they were also divided into three from side-to-side, with a central axis and lobes either side called pleurae. Their heads were also symmetrical, with a central portion called the glabella flanked by fixed and free cheeks. Many trilobites had heads with spiky hind corners known as genal spines.

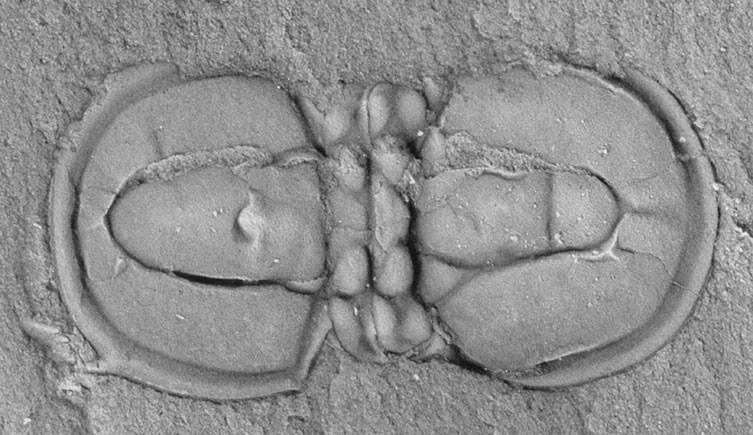

The trilobite Calymene is a good example of the three-lobed structure and is thought of by some as a typical trilobite.

Trilobites were armoured on the top side of their bodies, but what was under this hard exoskeleton?

We have lots of fossils showing the hard upper exoskeletons of trilobites, but fossils of their soft underparts are much rarer. We know that in life trilobites had antennae protruding from the head, which were used to chemically sense the world around them. They also moved about on jointed legs, with three pairs of legs attached to the head and one pair attached to each of the thoracic and tail segments.

How old are trilobites?

Trilobites appeared in the Cambrian Period, which lasted from 538 million to 485 million years ago. At the beginning of the Cambrian Period, the rate of evolution was exceptionally high. It’s a period of time often called the Cambrian explosion and is one of the most important milestones in the history of life.

The first trilobites are known from around 520 million years ago, making them about 100 million years older than the first shark and 290 million years older than the first dinosaur.

Trilobites lasted for more than 250 million years, surviving through six geological periods. They died out towards the end of the Permian Period. Our own species has only been around 0.1% as long as trilobites lasted.

The age of trilobites

How trilobites actually evolved remains a mystery. They appear in the Cambrian rocks abruptly, and the fossil record shows a variety of distinct early species popping up around the world at this time.

A sudden appearance such as this could suggest that we’re missing some considerable part of their evolution from the rocks of the very early Cambrian. But, while we often think of evolution as slowly plodding along, it can also occur at highly accelerated rates, which could help to explain their dramatic debut.

Trilobites will have evolved from more primitive arthropodan organisms. There are older animals that look a bit like trilobites, such as the seemingly segmented Spriggina from 550-million-year-old rocks in Australia. However, scientists now think they’re unlikely to be related to trilobites.

Spriggina looks a bit like a trilobite, but it’s unlikely that they’re related. Image © Matteo De Stefano/MUSE via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

From the Cambrian explosion onwards, trilobites came to be one of the dominant parts of the ocean fauna. In fact, the Early Palaeozoic has been dubbed ‘the age of trilobites’.

How many types of trilobite are there?

More than 20,000 species of trilobite have been described.

If you’re looking for a ‘typical trilobite’, Richard says the two-centimetre-long Calymene is a prime example. This species is a perfect example of the three-lobed layout of trilobites.

Some trilobites were far more extravagant, however. For example, Walliserops with its large trident protruding ahead of it or Comura with its elegant spines. There’s also a species of Cyclopyge whose eyes had fused together to become one large ‘super eye’ and Onnia with genal spines far longer than its body.

Onnia trilobites had long structures protruding from the hind corners of their heads called genal spines. Image © Luis Fernández García via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

So far, the smallest trilobite found is Acanthopleurella stipulae. At 1.5 millimetres in length, it’s not even as wide as a strand of spaghetti. The largest is the 72-centimetre-long and 40-centimetre-wide Isoteus rex.

Some of their characteristics likely helped make trilobites specialised to certain lifestyles and habitats. For example, spines might have evolved to put off predators such as early jawed fishes.

The abundance of trilobites and the fast evolution of new species makes these extinct animals excellent index fossils, which means we can use them to help us work out the age of rocks. When index fossils are found around the world it tells us that the rocks that contain them were laid down around the same time.

Walliserops trilobites had large tridents protruding from their heads. These might have been used in competition for mates.

Trilobite eyes

Trilobites had unique eyes. Look closely and you’ll see that lots of them are made up of many hexagonal lenses. They look a bit like the compound eyes of a fly, but one thing that sets trilobite eyes apart is that they had crystal eyes.

‘Other arthropods have mostly developed soft eyes, the lenses are made of cuticle similar to that constructing the rest of the body,’ Richard explains. ‘Trilobite eyes are made of calcite. This makes them unique in the animal kingdom.’

Trilobite eyes were made from calcite - something no other animal is known to have had before or since. This tower eye belongs to the trilobite Erbenochile erbeni.

Most trilobite eyes were stacked prisms of calcite that all pointed in slightly different directions. It’s likely that the more prisms they had, the better their eyesight. Species could have anywhere from one to several thousand lenses.

Their eyes can tell us how and where different trilobites might have lived. Some trilobites with giant bulging eyes were probably swimmers in the open ocean that needed to keep watch for prey. Whereas trilobites living on the seafloor might have needed to look out for food, mates, rivals and predators around them. Erbenochile, for example, had strange, tower-like eyes that were well elevated and probably able to scan for prey at a distance.

Asaphus kowalewskii had prominent, protruding eyes on stalks.

Other trilobites had no eyes at all. These species might have buried into muddy seafloors or lived in deeper, darker parts of the ocean where sight was obsolete.

What did trilobites eat?

Some trilobites were predators, while others survived by scavenging. They might have fed on worm-like creatures and other invertebrates that inhabited the seafloor.

In 2023, scientists reported evidence of a trilobite’s final meal. They revealed that a specimen of Bohemolichas incola was found to have the remains of small crustaceans known as ostracods, bivalves and an extinct starfish relative called a stylophoran in its gut.

Swimming trilobites might have harvested plankton – small marine organisms that are carried along by tides and currents. Many species probably ‘grazed’ the mud on the seafloor. Some were filter feeders that would have sifted food particles out of the water and sediment around them.

There were also trilobites that may have had symbiotic relationships with sulphur-eating bacteria. Some living creatures, such as clams, can cultivate these bacteria and use them for food. The discovery of trilobite fossils in what would have been sulphur-rich environments suggests they might have done similar, perhaps growing the bacteria in their gills.

Comura trilobites lived during the early Devonian. Their long spines might have evolved to help deter predators.

‘It’s likely that the earliest growth stages of many trilobites were part of the plankton, feeding upon tiny plants or maybe other larvae, just as baby barnacles or shrimps do today,’ Richard notes.

Trilobites would have had predators of their own. For a long time, scientists suspected Anomalocaris, an arthropod from a now-extinct group known as radiodonts. But recent research suggests some of these large predators might actually have preferred soft-bodied prey rather than trilobites.

Instead trilobites were probably hunted by large molluscs related to Nautilus, which are frequently found in the same rocks as trilobites. The start of the Devonian Period saw the appearance jawed fishes, which could also have eaten trilobites. Spiny trilobites probably stood a better chance of surviving at this time.

Trilobite sex lives

Baby trilobites looked quite different to the adults. Trilobites started out as tiny larvae called protaspides. To grow, they regularly moulted, subtly changing each time.

‘If a trilobite had eight segments… the babies would add segments one at a time until eight were reached, and after that would continue to get larger moult after moult without any more segments being added,’ Richard explains.

As for the step before baby trilobites, the discovery of a fossil featuring what are interpreted to be claspers may have solved the mystery of how these prehistoric animals mated. Males might have used claspers to hang onto the female during mating, in a similar way to modern horseshoe crabs.

This is an Agnostid trilobite. It was blind and had only two thoracic segments.

Other clues for how to tell male and female trilobites apart are scarce. However, recent research suggests that Wallopseris trilobites may have used their tridents in sexual combat, similar to how male stag beetles use their horns in competition for mates.

Why did trilobites go extinct?

Trilobites were great survivors. The group lasted for more than 250 million years, though there was fluctuation over that time.

At the end of the Cambrian, extinction events eradicated many of the early trilobite groups. Then at the end of the Ordovician Period, 440 million years ago, an ice age refrigerated the world and trilobites took another hit. This was the end for giant-eyed, free-swimming Telephinidae trilobites, for example. But the groups that survived into the Silurian Period bounced back, diverging into as many species as before.

In the Devonian Period that followed some of the most remarkable spiny trilobites appeared. However, during the Frasnian-Famennian events at the end of the Devonian, deoxygenated waters killed off coral reefs, an important habitat for many trilobites.

Phacops survived until the Late Devonian. These trilobites had very complex eyes with drop-shaped lenses rather than hexagonal ones. Image from Tomleetaiwan via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

This wasn’t the end for trilobites, but only a group called Proetida continued into the Carboniferous and Permian periods.

‘Proetide trilobites spread out into many of the ecological niches that had been occupied in earlier times by trilobites from a richer selection of families,’ Richard says.

‘They spread into deep water, and into newly re-established coral reefs. As a consequence, some of these late trilobites came superficially to resemble their ecological twins recovered from Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian rocks.’

By the Permian Period, trilobites were less common and only a few genera remained. This period ended in a mass extinction sometimes called the Great Dying, where 90% of animals were wiped out. Trilobites disappear from the fossil record just before this catastrophe.

The last trilobites were mostly found in shallow, tropical seas, possibly making them more vulnerable to climate change. In the end, trilobites, a group that had once dominated our planet’s oceans, slowly fizzled out before the Triassic Period began.

Are there any trilobites left?

Sadly not, trilobites are extinct. There’s no evidence of them in the fossil record after the Permian. There are also no hints of living trilobites hiding in the deep ocean - so far there’s been no ‘trilobitic coelacanth’, as Richard puts it.

Chitons’ shells are made up of plates, which makes them look like the segmented armour of a trilobite. © Randy Bjorklund/ Shutterstock

There are a few living animals that look a bit like trilobites, such as intertidal molluscs called chitons, woodlice and ocean-dwelling isopods. Their appearances might be similar, but none are closely related to trilobites.

The closest living relatives of trilobites might be horseshoe crabs. Their hardened exoskeletons give them a superficially similar appearance. Horseshoe crab larvae are also reminiscent of the protaspis stage of young trilobites.

Horseshoe crabs may be the closest living relative of extinct trilobites.

Trilobites in the UK

You can find plenty of trilobites around the UK. We have fossils of trilobites that lived from the Cambrian through to the Carboniferous.

The first ever record of trilobites was from the UK. In 1698, naturalist Reverend Edward Lhwyd published a drawing of a trilobite found in Carmarthen, though at the time it was mistaken for the skeleton of a fish. Almost 100 years passed before the group was officially named ‘trilobites’ by German naturalist Johann Walch.

Trilobites in Wales have also masqueraded as butterflies, with legends of the wizard Merlin having turned them to stone. In reality, these petrified insects are the Ordovician trilobites Merlinia. This case of mistaken identity comes from Merlinia specimens where the tail has broken away from the body and fossilised, giving it the appearance of butterfly wings.

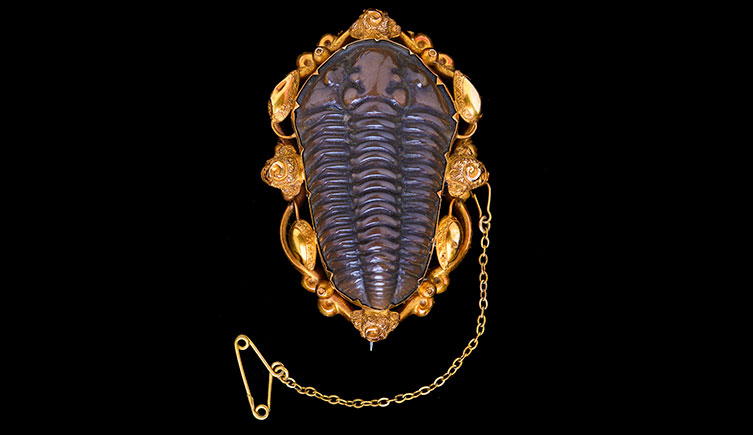

Another famous UK trilobite is Calymene blumenbachii. They were first found in the eighteenth century at a site known as the Wren’s Nest in Dudley. Given the nickname ‘Dudley locust’ by local miners, these popular trilobites ended up on the Dudley County Borough Council’s coat-of-arms.

A brooch made from a Calymene blumenbachii trilobite fossil. These trilobites were popular collectors’ items and by the mid-nineteenth century people also enjoyed wearing them as jewellery.

Fascinated by trilobites? Discover where you can find these and other fantastic fossils in the UK.

This article includes information from the book Trilobite! Eyewitness to Evolution by Professor Richard Fortey.

Discover oceans

Explore life underwater and read about the pioneering work of our marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media