Giant isopods look like monstrously sized woodlice and can live in the deep sea, beyond the reach of daylight. But how much do we really know about the lives of these crustaceans?

Giant isopods are large relatives of the woodlouse

Despite their intriguing looks and substantial size, relatively little is known about giant isopods. We know where they live and how they fit into taxonomy (sitting together in the genus Bathynomus). But these unusual animals have yet to be the focus of extensive studies and are still somewhat of a mystery to science, despite being first discovered in 1879.

Miranda Lowe, Principal Curator of Crustacea, explains some of what we know so far about these giant waterborne relatives of the pill bug.

What is a giant isopod?

There are a lot of animals living on the seabed that seem strange to us on land. Giant isopods can live 500 metres or more below the ocean surface. But these 14-legged goliaths are relatives of the little woodlice you might find scuttling about in the garden - albeit distant cousins.

Giant isopods spend the majority of their time on the seabed, waiting for food to fall from higher in the water column

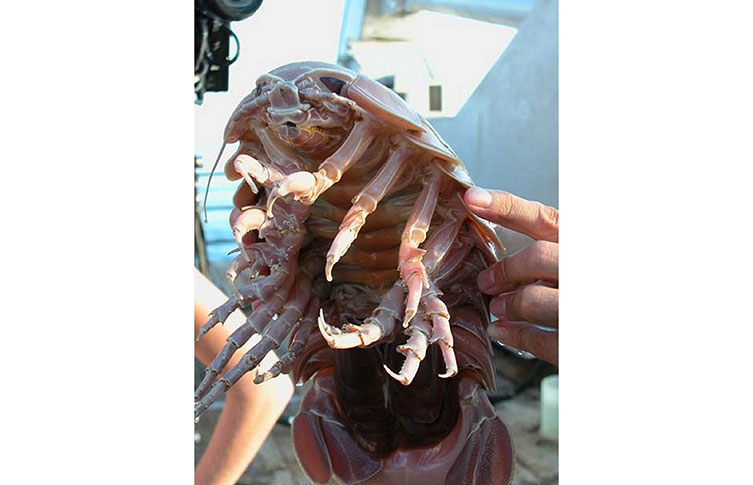

The largest isopods are the species Bathynomus giganteus. When it comes to their size, Miranda describes the crustaceans as being 'more than a handful'.

These arthropods are much larger than your usual pill bug. They can reach more than 30 centimetres from head to tail.

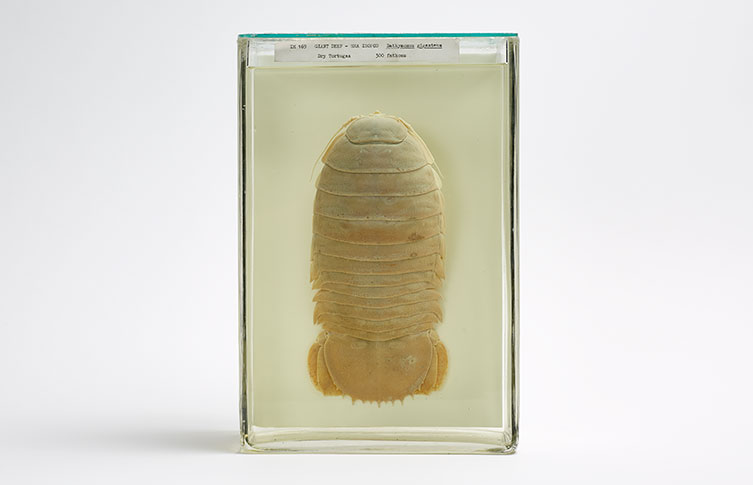

'We've got one in the collection that was collected from Dry Tortugas, in the Florida Keys, USA,' says Miranda. 'It was collected from 300 fathoms, which is about 549 metres below the ocean surface, but they've been known to go deeper.

'The problem with any deep-ocean animal is that not much is known about their lives. You have to put down expensive submersibles and observe them over a long period of time. Collections of them are really quite small.

'They're a nice curiosity, but there aren't many people formulating research around them, so there are still a lot of unanswered questions.'

Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017

What do giant isopods eat?

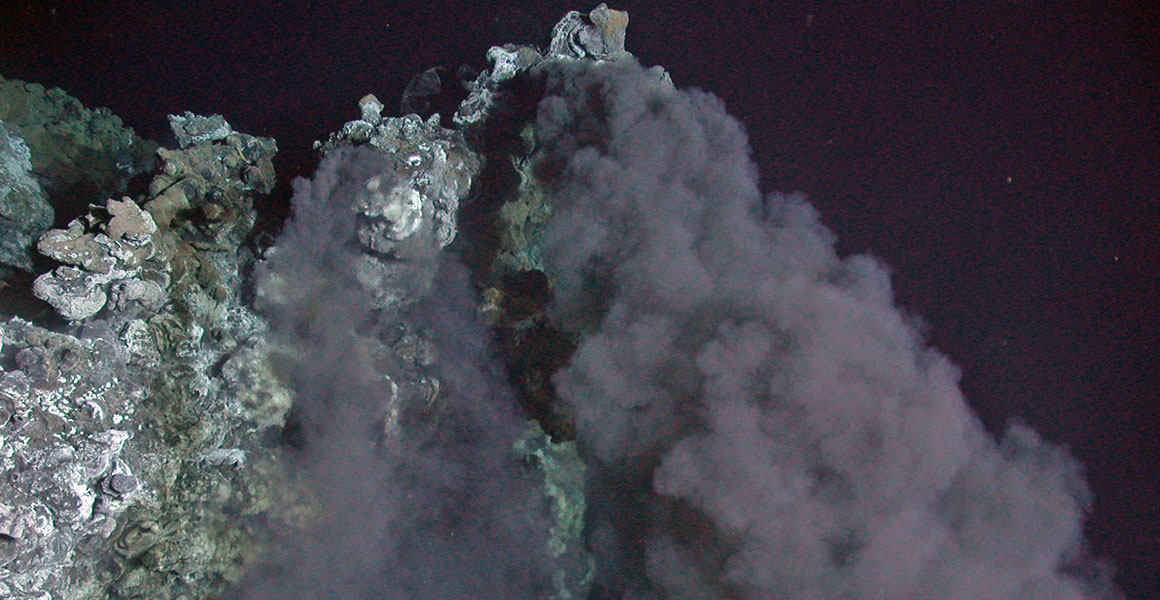

Resources are scarce in the deep sea. Isopods rely on food falling from closer to the surface, as the seafloor is mostly barren. Occasionally big parcels of food reach the seabed, such as whale falls.

'From what we know so far, they're not as fierce as they look,' says Miranda. 'They are scavengers and would eat any of the falling marine snow and what's enveloped within it - so things like crab flesh and marine worms'.

Giant isopods have limited predators - this could be one of the reasons they're so large © NOAA Photo Library via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

When ocean animals die and begin to decay, parts that aren't consumed nearer the surface begin to fall towards the seabed. It can look white and fluffy, like snowflakes.

But due to the scarcity of food, animals often have to be patient and wait for long periods to get what they need. This could mean waiting for years. Their metabolism is incredibly slow - a giant isopod kept in captivity in Japan reportedly survived for five years without eating.

Survival in the deep sea

Giant isopods express deep-sea gigantism, reaching in excess of 30 centimetres. There are a number of theories on why they might have become larger.

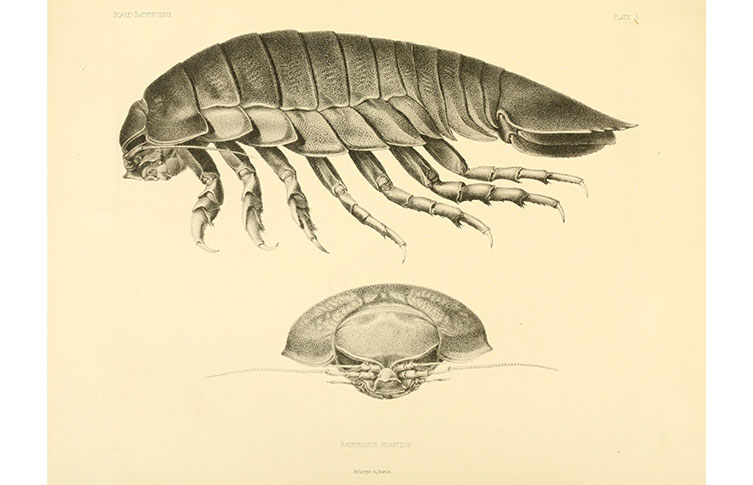

Giant isopods were first discovered in 1879 by French zoologist Alphonse Milne-Edwards in the Gulf of Mexico. This illustration was published in Milne-Edward and E LBouvier's 1902 volume, Les Bathynomes, via Wikimedia Commons

In the deep ocean, animals need to carry more oxygen, so their bodies can become bigger and have longer legs.Another possible factor in increased body size is that the deeper an animal lives, the less predators there are. This would mean that animals can safely grow to larger sizes.

'They don't have many natural predators,' Miranda says. 'They've got a really hard outside shell, like other crustaceans, and there's not much meat in the animal - there's less meat than in a crab. So there aren't a lot of other animals that are going to want to eat it for anything substantial.'

A giant isopod specimen collected from Dry Tortugas in the Florida Keys, USA

Not only does the deep offer minimal food, there is also a lack of light. The isopods have sensory adaptations to help them navigate in the dark.

'The deeper you go, the less light there is. So for Bathynomus, it has very long antennae which are about half the length of its body. They're a large sensory organ so they can feel their way around. Giant isopods also have very large eyes in comparison to their body too,' explains Miranda.

The isopods also have little hooked claws at the ends of their legs. These make the animal more stable on the ocean floor.

Miranda explains why you'll often find the giant isopod's land-dwelling cousin, the woodlouse, lurking in damp places:

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Dive in

Find out more about life underwater and read about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Sorry to surface...

But are you a deep-sea enthusiast? Explore the inky depths in our expert-led, online and on-demand course Deep Sea, available now.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media