Whale carcasses take decades to fully decompose and can provide food for an entire ecosystem on the dark depths of the ocean floor.

When whales die, they eventually sink to the bottom of the ocean. This is known as a whale fall. © Maksimilian/ Shutterstock

Dr Adrian Glover, a Museum expert in deep-sea biodiversity, sheds light on life after death for whales.

What is a whale fall?

Decay sets in soon after the death of a whale, as the insides begin to decompose. The animal then expands with gas and sometimes floats up to the ocean's surface, where it can be scavenged by sharks and seabirds.

Eventually the ocean giant will begin to sink, falling kilometre after kilometre, until finally coming to rest on the seabed. This is when the carcass becomes known as a whale fall.

Whale falls can nourish an entire ecosystem of deep-sea creatures, from large scavengers to microscopic bacteria. They provide inhabitants of the mostly deserted ocean floor with a sudden and immense source of food.

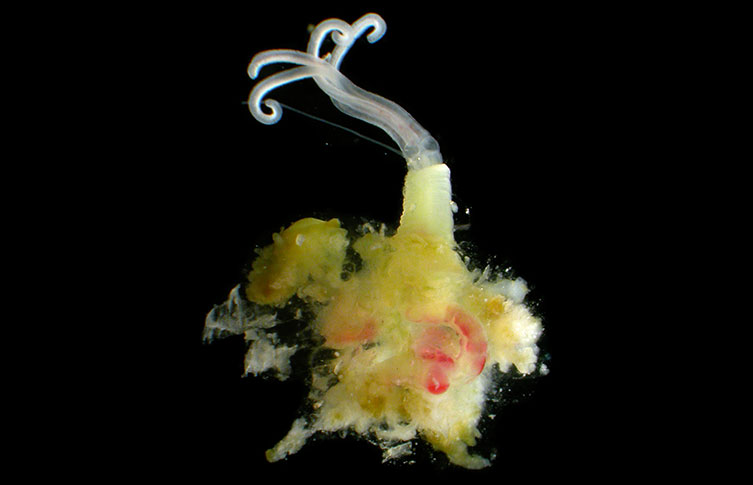

Osedax antarcticus is just one of the worm species that can be found in the population of animals accumulating at whale falls © Thomas Dahlgren

Once the whale lands on the seabed, hagfish, sleeper sharks, crabs, lobsters and a host of other scavenging animals eat the blubber and muscles down to the bone.

A single whale can provide animals with sustenance for up to two years during this initial scavenging stage.

A natural whale fall is a rare sight, so scientists have few opportunities to study whales that have died and naturally sunk in the open ocean.

Whale falls that are observed by scientists are usually dead stranded whales intentionally sunk in a particular location to be studied in detail.

Adrian says, 'The death of a whale leads to a whale fall on the sea floor.

'Only a few whale falls have been happened across naturally. The rest have been from sinking experiments.'

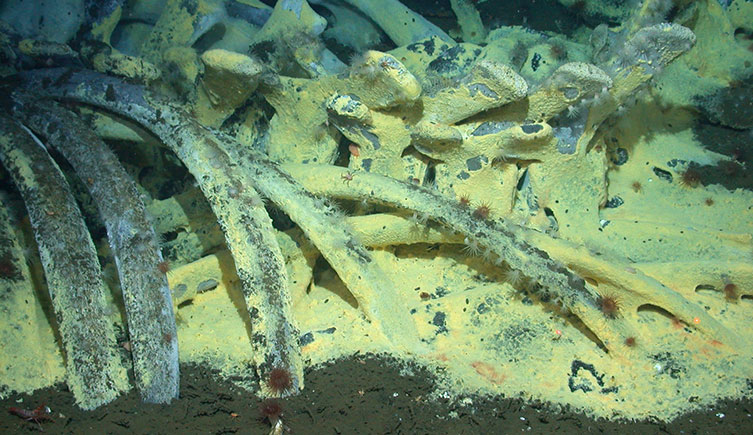

A grey whale was planted on the seafloor in 1998. This image was captured six years later, by which time communities of invertebrates and bacteria had taken over the carcass. Image courtesy of Craig Smith, University of Hawaii via Wikimedia Commons.

Bone-eating zombie worms and snot-flowers

Large scavengers may reduce the carcass to a pile of bones, but there is still plenty of food left for some much smaller diners.

Sea snails, bristle worms and shrimp devour any remaining scraps of blubber or muscle. They will also eat organic matter that is emitted from the carcass.

Polychaete worms such as Vigtorniella flokati feed on the tissues of the dead whale, helping to reduce the carcass to bare bones.

'The animals accumulate in numbers around the whale,' says Adrian.

'They will move in and grow to adulthood there. It becomes an entire population.'

Zombie worms - species in the genus Osedax - were first discovered on a three-kilometre-deep whale fall in 2002.

Adrian explains, 'These are the most important animals responsible for the process of breaking down the bones.'

Also known as bone worms, these invertebrates chemically eat the bones, breaking down elements such as collagen and fat using specialised methods.

Additionally, they push oxygen into the bones, a process which speeds up decay.

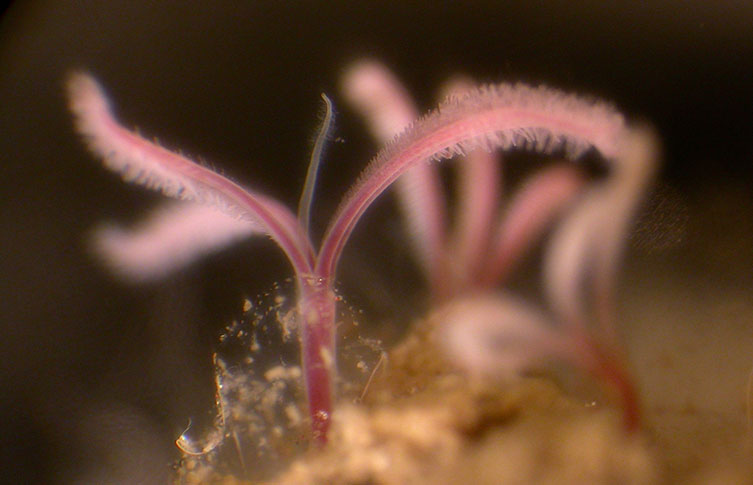

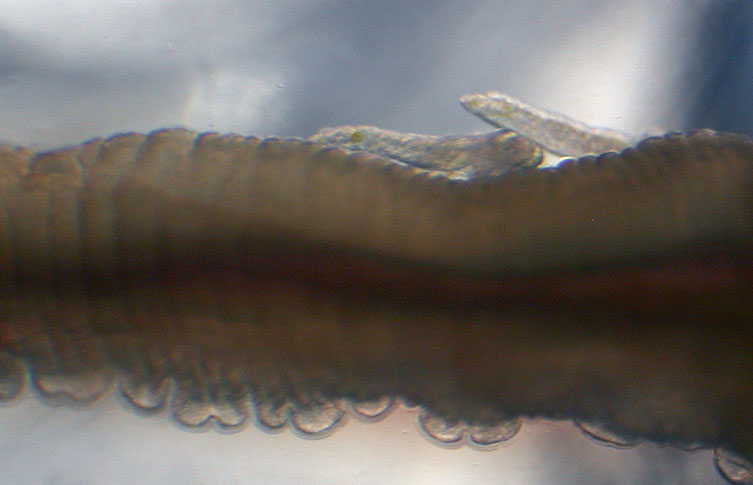

The worms, such as Osedax mucofloris - a name which literally means 'bone-eating snot-flower' - bore their bacteria-filled root system into the bone, leaving their feathery plumes waving in the open water, taking in oxygen.

Osedax mucofloris, a species of bone worm first discovered in 2005 on a whale fall off the coast of Sweden, is coated in a layer of mucus © Helena Wiklund

Deep in these roots, the worms and bacteria make acid and enzymes to break down different elements of the bone.

'Some Osedax males live on the outside of the female's tubes, fertilising eggs as they are released,' says Adrian.

'The oviducts release lots of eggs into the water column which hatch into larvae. They then settle on nearby bones or can drift to another whale carcass.'

These small scavengers can spend as long as 10 years harvesting the remains of a whale.

Osedax males, visible here on the upper side of the female trunk, are dwarfed in size by their female counterpart and live in large numbers on the outside of their bodies © Thomas Dahlgren

Chemoautotrophic animals and whale falls

While scavengers are at work digesting the bones, for 10 to 50 years the whale fall provides for a more specialised set of feeders. The bones are taken over by bacteria that produce hydrogen sulphide, a gas that smells of rotten eggs.

A process called chemoautotrophy is a way for animals to gain energy through this and other chemicals, rather than through food.

Specialised mollusc and tube worm species are chemoautotrophs that take advantage of whale falls, feeding on the chemicals released from the bones.

Before whale falls were well documented, it was thought that this type of biodiversity was only seen at cold-seep sites and hydrothermal vents, where hydrogen sulphide and methane naturally escape through the sediment.

But it is now acknowledged that whale falls offer a unique stepping stone for specialised animals from these sites to disperse across the predominantly desolate ocean floor.

Osedax worms, such as O. antarcticus, accumulate in large numbers on whale bones, spending las long as 10 years feeding from them © Thomas Dahlgren

How can stranded whales teach us about whale falls?

Not all whales sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, however.

Some instead become stranded on coasts around the world. Although efforts are often made to save them, without water to maintain their buoyancy, the weight of the whale's own body soon begins to crush the internal organs.

As smelly as 100 tonnes of decomposing flesh can be, a beached whale is a scientific goldmine - an opportunity to study a creature that is frequently beyond reach.

The Museum has been actively involved in the UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme since 1913, collecting information on the ocean giants that wash up on UK shores.

The primary goal in studying a stranding is to gather as much biological information as possible about the whale itself. For example, a spectacled porpoise that stranded in the Falkland Islands in 2017 is now giving Museum scientists insight into the lives of these elusive cetaceans.

The feather-like plumes of O. antarcticus are used to take in oxygen © Thomas Dahlgren

Because happening upon a natural whale fall is so rare, scientists can use strandings as an opportunity to take and strategically sink parts of these animals to help improve understanding of the process of decay.

Whales are exceedingly important in the marine ecosystem. They are efficient feeders, sitting high up in the food chain.

In death they provide life for hundreds of marine animals for up to 50 years, further proof of the vital role they play in the life cycle within Earth's oceans.

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Discover oceans

Find out more about life underwater and read about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Fascinated by the ocean’s depths?

Dive into our online, on-demand Deep Sea course and start exploring the mysteries of the deep today.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media