Sea urchins are globe-shaped creatures that live on the ocean floor.

Many beachgoers have had the misfortune to feel a sting from their spines, but how much do you know about the lives of these animals?

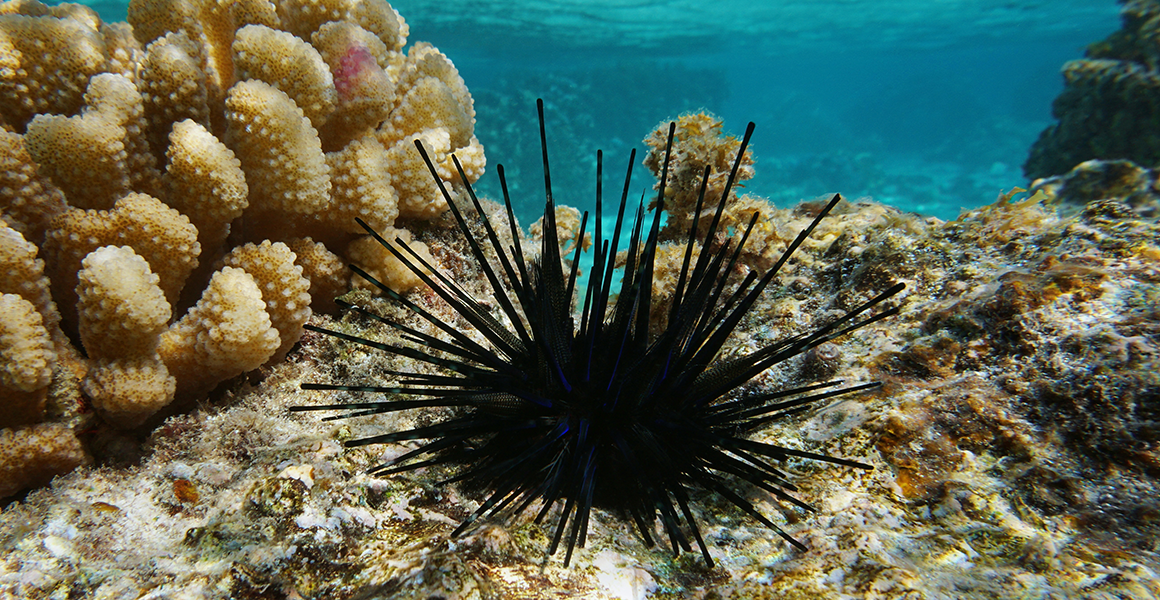

Sea urchins, scientific name Echinoidea, are spiny creatures that live on the ocean floor. © Damsea/ Shutterstock

Sea urchins are globe-shaped creatures that live on the ocean floor.

Many beachgoers have had the misfortune to feel a sting from their spines, but how much do you know about the lives of these animals?

From a fascinating symmetrical structure to deadly-looking spines, unique mouthparts and clever techniques for moving about on the seafloor, discover the extraordinary world of sea urchins.

Sea urchins belong to a group of marine invertebrates called Echinodermata, which means spiky-skinned. Animals in this group are known as echinoderms and include sea cucumbers, sea lilies, brittle stars and starfish, otherwise known as sea stars.

Sea urchins can be found in all of Earth’s oceans. Some species live between the high and low tide lines near the seashore. Others live in the deep ocean, mostly up to 5,000 metres below the surface. The deepest a sea urchin has ever been recorded at is 7,340 metres.

Sea urchins first appeared around 450 million years ago. Of the groups present in our oceans today, the first to evolve were the Cidaroidea, appearing about 268 million years ago. These primitive sea urchins often have stubby, rounded-off spines.

The second group of sea urchins, Euechinoidea, evolved a little later and include the spiky creatures you may be more familiar with. This subclass are considered ‘modern’ sea urchins.

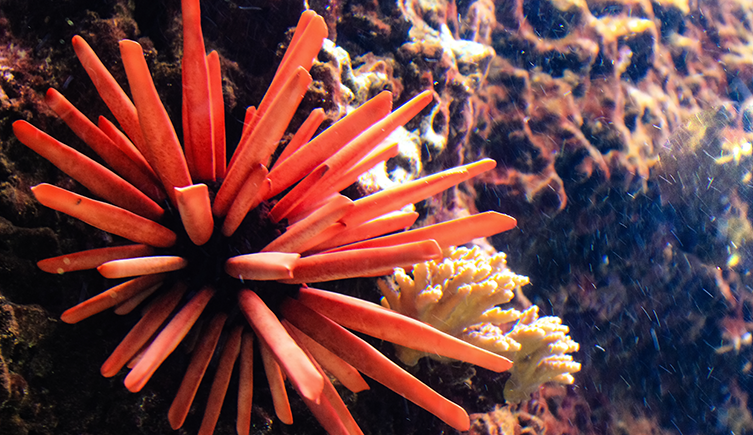

The slate-pencil urchin, Heterocentrotus mamillatus, is an example of the Cidaroidea sea urchins, the only living order of the subclass Perischoechinoidea.

The most easily recognisable sea urchins are round, often brightly coloured and covered in sharp-looking spines. In fact, ‘urchin’ comes from an old word for hedgehog owing to their similar-looking spiky armour.

However, there are more than 1,000 species of sea urchin, with varying characteristics.

‘Most modern sea urchins are round - they’re the regular sea urchins,' explains our echinoderm curator, Hugh Carter.

‘But about a quarter of sea urchins have modified that body plan massively. For example, there are sea urchins who evolved a flatter shape and smaller spines to adapt to life burrowing in sand. You also get really weird deep-sea urchins with strange bodies that don’t look like anything else!’

We don’t know as much about these deep-sea urchins yet as they are hard to reach and very fragile. This makes it very difficult to bring them up to the surface to study.

Like most echinoderms, sea urchins have an internal skeleton called a test.

‘A sea urchin’s test is made from a type of calcium carbonate called stereom, a porous structure that holds the sea urchin together, like jigsaw pieces cemented in place,' says Hugh.

Sea urchin tests have five symmetrical parts arranged around a central point, like the segments of an orange. This isn’t always obvious from the living creature but can be seen from the test when dried.

The dried test of a sea potato urchin, which shows how the skeleton is divided into five sections – this is called radial symmetry. © Goran Lakovic/ Shutterstock

Sea urchins cannot swim. They live and move along the seafloor, favouring hard surfaces such as coral and rocks. They have appendages called tube feet that often have suckers at the tip. The sea urchin uses the hydraulic pressure of water moving in and out of their tube feet to move about slowly. They can also propel themselves along with their spines. That’s pretty impressive, considering sea urchins don’t actually have brains!

Some sea urchins also have pincer-like organs that look like little jaws. These are called pedicellariae. They are mostly used for self-defence or to remove debris from the animal. The pedicellariae in some sea urchin species are venomous.

Sea urchins, like other echinoderms, get about using their tube feet. Water is moved into and out of the tube feet to create movement. Image © Jerry Kirkhart via Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Sea urchins are omnivores. Their main diet is algae, but they eat some animals too, such as sea cucumbers, mussels and sponges.

As sea urchins move about on their tube feet, they scrape algae into their mouth. Their unique chewing organ is called the Aristotle’s lantern and includes complex jaws and five self-sharpening teeth.

If something nutritious lands on a sea urchin’s body out of reach of their Aristotle’s lantern, they’ll use their tube feet to pass the food to the mouth. Since they scrape up food from the ocean floor, it makes sense that a sea urchins’ mouth is on its underside. They excrete waste from an anus at the top of their body.

Close up, the mouth parts of the sea urchin - also called Aristotle’s lantern - could be mistaken for something from a science fiction movie! This is a flower urchin specimen from our echinoderm collection.

Most sea urchins reproduce by females releasing eggs directly into the water. These are then fertilised by sperm. Some species’ females hold eggs in their spines to better protect them.

Most sea urchins release millions of eggs at one time and live in huge colonies to increase the chances of reproductive success. There are also more solitary species, however.

Some tropical species of sea urchins have venom in their spines. If you’re unlucky enough to step on a venomous urchin, the toxins can enter the body through the puncture wounds.

Some sea urchins’ venoms can cause nasty symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and breathing difficulties, but according to Hugh, even the most venomous sea urchin has only been linked to one reported human death.

Here are just a few of the many fascinating sea urchin species:

A flower urchin © unterwegs/ Shutterstock

The flower urchin, Toxopneustes pileolus, is beguiling to look at, but it is the most toxic sea urchin species. In fact, Toxopneustes means ‘poison breath’.

Flower urchins get their name from their appearance, with petal-like pedicellariae covering their bodies. These hide their short, blunt spines. Unlike most other urchins, flower urchins deploy their venom through the pedicellariae rather than through their spines.

A sea potato. Image © Hans Hillewaert via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The sea potato, Echinocardium cordatum, is covered in short beige spines which give it a furry appearance quite distinct from its sharper-spined cousins.

These sea urchins burrow into the seafloor. Their fuzzy spines trap air, preventing the urchin from suffocating under the sand.

Sea potatoes are also known as heart urchins due to the shape of their test. You can find them in the waters around the UK.

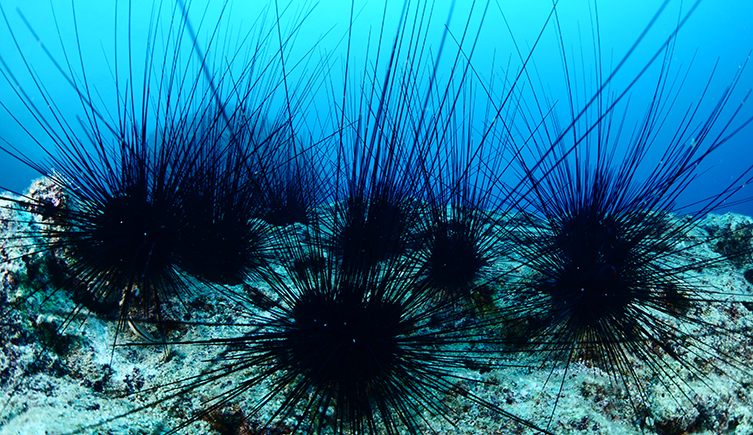

Black long-spined urchins © scubadesign/ Shutterstock

Black long-spined urchins from the genus Diadema are found in all tropical oceans.

Some have spines that can grow to a length of 30 centimetres. If they stab you, the spines can sometimes break off in the skin - though the human body will dissolve these fairly quickly.

A slate pencil urchin © Molly NZ/ Shutterstock

The slate-pencil urchin, Heterocentrotus mamillatus, is a member of the Cidaroidea order of sea urchins. This group often has much blunter spines.

Slate-pencil urchins are found in the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific and are particularly common around Hawaii.

A sand dollar © Lavendulan/ Shutterstock

Sand dollars, a group known as Clypeasteroidea, are an example of irregular sea urchins.

Sand dollars are much flatter than other urchins, an adaptation that better suits their environment. They also have much shorter hair-like miliary spines all over their bodies which are used for burrowing into sand.

A green sea urchin. Image © Klaus Kevin Kristensen via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 4.0

The green sea urchin, Psammechinus miliaris, can be spotted on rocky shores around Britain. This species’ spines are purple at the tips, so it is sometimes also called the purple-tipped urchin.

This is not the only species given green sea urchin as a common name, however. Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis is also greenish in colour and found across the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Some sea urchins have symbiotic relationships with other species.

The carrier crab, Dorippe frascone, has been known to wear sea urchins like a hat to protect itself from predators!

Sea urchins are considered a delicacy in many countries around the world. They’re especially popular in Japan where the reproductive organs, or gonads, are called uni and enjoyed in sushi. In New Zealand, kina, Evechinus chloroticus, have long been part of the traditional Māori diet.

It’s not just humans that have found a way past the sea urchin’s spiny exterior. Their predators include a wide variety of fish, starfish, crabs and sea otters.

‘Sea otters lie on their backs with sea urchins on their chest and whack them with a rock to eat what’s inside,’ says Hugh.

Sea urchins are a popular delicacy in Japan and are also enjoyed in the Mediterranean, where they are often eaten fresh with a bit of olive oil and a dash of lemon juice. © Quality Stock Arts/ Shutterstock

Sea urchins are not used by people solely in cuisine. Perhaps because of their mysterious shapes, fossils of sea urchin tests have also historically been used as protective amulets to ward off evil.

‘In southern England, some sea urchin fossils were traditionally thought to be thunderbolts frozen in rock,’ says Hugh. These ‘thunder-stones’ were thought to protect a house from being struck by lightning.

More recently, sea urchins became model organisms for biological research. In 1875, German zoologist Oscar Hertwig was the first person to observe sexual reproduction at the cellular level by looking at the eggs and sperm of sea urchins under the microscope.

In 2001, the Nobel Prize for Medicine was given for the discovery of the cell cycle in sea urchin embyros.

The European edible sea urchin, Echinus esculentus, is considered Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The population of purple sea urchins, Paracentrotus lividus, in the Mediterranean is also in severe decline. Also known as the stony sea urchin, this species might be affected by warming sea temperatures, disease and overexploitation by people.

Out-of-control colonies of sea urchin have been known to cause destruction by mowing through environmentally valuable kelp forests. By nibbling the lower stems of entire forests of kelp, sea urchins can cause the seaweed to drift away and die. This behaviour forms desolate areas called urchin barrens. These population explosions are thought to be linked to the historic hunting of sea otters. These mammals are top predators of sea urchins and help keep their colonies under control.

Healthy kelp forests are a hugely valuable habitat, but they can be decimated by an invasive population sea urchins. Image © Shaun Lee via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Sea urchins are sensitive to changes in their environment. They can act as an early warning system for potential problems in the ecosystem, such as rising temperatures.

‘Ocean acidification and rising temperatures are probably the biggest long term threat to sea urchins as a whole,’ says Hugh.

‘Increasing ocean acidification increases the rate at which calcium carbonate dissolves. As things get more acidic, it will likely become harder and harder for sea urchins to accumulate enough calcium carbonate to make a solid test and their tests will get thinner and weaker. Experiments in the lab have shown this can happen with even very minor increases in acidification.’

Sea urchins help illustrate why it’s so important to protect the balance of nature in our already threatened ocean ecosystems.

Explore life underwater and read about the pioneering work of our marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media