This is the question I'm most frequently asked (at least at work). Does it have an answer? Not really. No organisms need a 'point' (there are no entrance exams in evolution), but wasps do impact on our lives in useful and surprising ways.

Read on to discover why wasps matter and find out more about some of the most wonderful species.

1) They are beautiful.

Camouflage, communication - especially communicating the fact that they might sting you - and being conspicuous in dark undergrowth are all reasons why so many wasps have striking colour patterns. Iridescent, metallic-looking colours have evolved many times. Black and yellow stripes are classic warnings to birds and mammals that they can sting, so best left alone.

Ormyrus nitidulus - a common British parasitoid of gall wasps.

Ophion obscuratus - nocturnal ichneumonid, common and widespread.

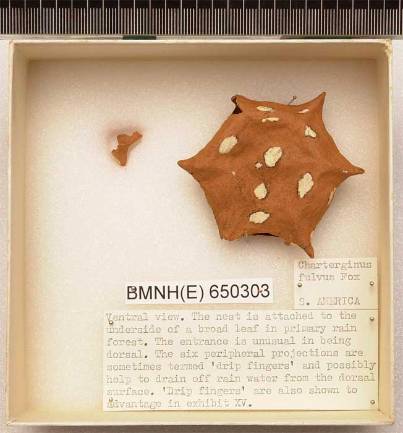

Nest of Charterginus fulvus, a South American paper wasp.

2) They are useful.

Wasps are not just here to provide entertainment at picnics. They help us to control pests that would otherwise damage our gardens and food crops.

Vespids are a large family of wasps that include familiar nest-building species you might see flying around your garden. Wasp larvae are fed on flesh, usually of other insects, such as caterpillars and aphids. So, wasps can be useful around the garden by eating pests (the adults just need sugar, they become annoying when they're out for themselves, as the colony collapses late in the summer). But these predatory wasps, though they are the most familiar to us, are just the tip of the wasp iceberg. Together with ants, bees, sawflies and many families of parasitoid wasps, they comprise the order Hymenoptera.

Vespula vulgaris - the vespid that everyone is most familiar with

There are hundreds of thousands of parasitoid species out there: these lay their eggs in or on other insects, which their larvae then eat alive. These parasitoid wasps are responsible for the deaths of huge numbers of insects, regulating populations, partly shaping the world around us by limiting numbers of vegetation-crunching caterpillars and the like. We harness this ability to find and parasitise particular insects by releasing some wasp species to control numbers of pest insects on crops: biological control. This saves us huge amounts of money.

3) They are interesting.

All wasps do something interesting. They attack other insects in sophisticated and often surprising ways. Every creature is, of course, potentially interesting (even beetles) but the intricate interactions of parasitoid wasps and their hosts is, you must admit, fascinating.

Cotesia glomerata larvae emerging from a large white (Pieris brassicae) caterpillar.

We know very little about the biology of the majority of parasitoid wasps, even in countries such as Britain, with a long and proud history of under-employed clergymen and country squires peering into bushes and sifting through soil for caterpillars. Here are two species from my garden, to illustrate the point.

Helorus rufipes, a wasp quietly going about its business in British woodlands and gardens.

The first wasp is Helorus rufipes. You don't get much more obscure than this. It's one of three British species of the family Heloridae, a family found over much of the globe but not one of the hymenopteran success stories, with only a small number of species. They're not very big and they are not very flashy but they do live in British woodlands and gardens and are quietly going about their business, laying eggs in lacewing larvae and eating them from the inside. This specimen was on the wall by my back door as I left for work one morning. But you won't find Helorus in many field guides or many online illustrations. Just one of many obscure families of Hymenoptera that fill our landscape.

What appears to be a new species of Netelia, an ichneumon wasp, found in my garden.

The second wasp is a species of Netelia, of the ridiculously successful family, Ichneumonidae. Ichneumonids abound, with over 2,300 species in Britain alone. Netelia is one of the more successful genera with a great many species found all over the world, including 25 species in Britain. This specimen was caught in the light trap that I use for catching moths in my garden, which is also a productive way of sampling nocturnal wasps.

For a while, I thought that this species was Netelia testacea, which is a name that you will often see online and in the literature, sometimes illustrated in field guides as one of the few ichneumonids apparently common and well known enough to be worth illustrating. There are many, many papers that reference the biology and distribution of Netelia testacea. Except that these are almost all wrong, and I was wrong.

I've checked out the identity of Netelia testacea and it's not what we thought. The well-known species usually illustrated as Netelia testacea is usually Netelia melanura and this species in the photograph, that I frequently catch in my garden, turns out not to have a name. So I need to describe a new species for one of the most common ichneumonids in my light trap, which is one reason these things are so interesting.

Further information

- There are, sadly, few online resources that provide a good introduction to the vast insect order, Hymenoptera. The Amateur Entomolgists' Society is useful.

- There are over 7,700 species of Hymenoptera in Britain; my introduction to the new checklist includes a table of species per family.