On Sunday I helped with a workshop at the Museum as part of the the nationwide 'Big Draw' initiative. ‘Experimenting with observational drawing, algorithms and natural form’ was the mutant offspring of the brilliant artists Gemma Anderson and Prof William Latham.

We meticulously observed natural history specimens then drew them. Then drew them from memory. This was before we started mutating various fundamental shapes according to William’s FormSynth rules which then took a further step as Gemma introduced fundamental rules of symmetry and body forms across the natural world and we evolved these forms through random processes in a practice Gemma calls isomorphogenesis. Which sounds like an interesting way to spend a Sunday, and it was.

I can’t draw

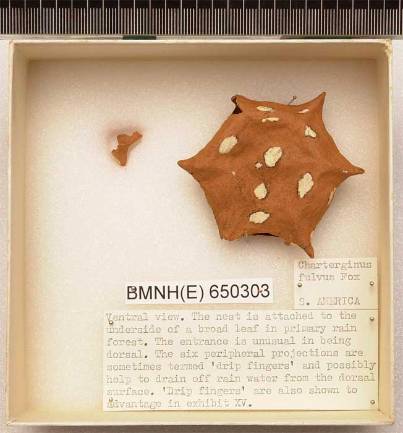

Puffer fish - In real life they look much more like a bad pencil sketch than that mounted specimen would have you believe...

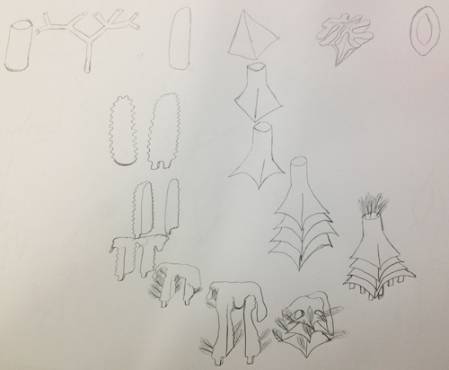

I’m rather embarrassed to show these pictures here. I hadn’t seriously held a pencil for probably 20 years and I was disappointed to discover that I can’t draw a nice curve, never mind sketch a dodecahedron. This took me miles outside of my comfort zone.

My attempt at drawing forms mutating according to rules of isomorphogenesis (this takes quite some explaining).

There were some seriously good artists in the room who produced some amazing drawings. But the principle is intriguing, even to the artistically challenged, such as me. My horribly drawn shapes evolve into weird and wonderful structures. There’s something strange going on, with parallels to evolution.

What does this have to do with wasps?

What’s the wasp connection here? The link is our collections at the museum. One of the pleasures of my job is to make the collections accessible to artists (I should point out this is only a small part of my job; I really am a curator, busily curating and stuff…).

Gratuitous wasp photo - Degithina davidi (Ichneumonidae) looking very welcoming.

Not long after I started at the Museum I was introduced to Tessa Farmer, who was an artist in residence for six marvellous months. Tessa took inspiration from the parasitoid wasps that I work on, and her malevolent little fairies adopted some of the behaviour of parasitoids in their quest to enslave and torment other creatures. Tessa’s installation in Hintze Hall (previously Central Hall) featured a stop-motion animation with brilliantly otherworldly sounds by Mark Pilkington, which created an eery atmosphere first thing in the morning, before the crowds filled the space.

Detail from Tessa Farmer's 'Little Savages' (2007), exhibited at the Natural History Museum, featuring a chrysidid wasp and an unfortunate fox (copyright Tessa Farmer).

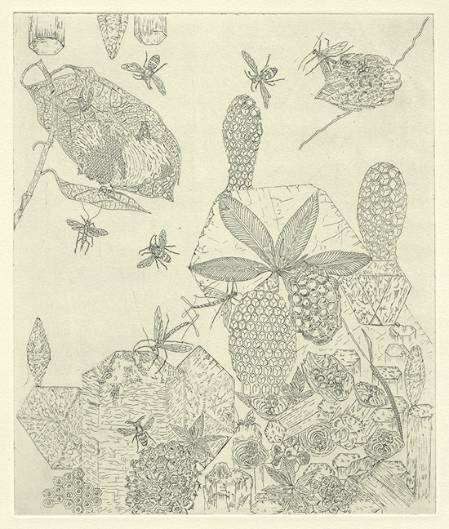

Returning to Gemma Anderson, Gemma has had a long association with the Natural History Museum, reclassifying our collections on the basis of shared forms and symmetries, rather than the classic taxonomy that we use to lay out our collections. So Gemma would draw a wasp nest, with its arrays of perfectly hexagonal cells and juxtapose it alongside hexagonal minerals, plants and other natural objects in beautiful dioramas.

Gemma Anderson's Hexagon etching, featuring wasp nests (and other hexagons) © Gemma Anderson.

Hexagons in wasp nests: nests of Apoica pallens, a neotropical polistine (paper wasp).

This process was termed ‘Isomorphology’ by Gemma. The next step, which we were experimenting with at Sunday’s workshop, is the introduction of evolution from ‘bauplan’ shapes (fundamental forms), which she calls ‘Isomorphogenesis’.

The art of evolution

Anyway, Tessa’s fairies evolved, and they continue to evolve in interesting directions, displaying ever more complex behaviours. Gemma’s shapes evolve in surprisingly unpredictable ways. Recently I met Daisy Ginsberg, a designer and artist who is exploring the possibilities and perils of synthetic biology, amongst other things. I gave a talk at a workshop she ran but Daisy was really interested in how we classify our organisms, when I gave a tour of the Hymenoptera collections.

The way we lay out our collections on taxonomic lines, reflecting the evolution of these insects, has directly influenced Daisy’s Design Taxonomy, futuristic biosynthetic cars that evolve to work efficiently in different climates and for different tasks.

Cars of the future: Daisy Ginsberg's 'Design Taxonomy'.

This got a lot of attention at the London Design Festival. As well as the wonderful premise, these model cars look like really tasty little cakes.

Art and wasps

These artists, and others I haven’t mentioned, have taught me the value of observing. They are incredibly good at observing the details of the specimens in front of them. Hopefully I’m not too bad at observing: after all, I am a taxonomist, looking at tiny differences and describing new species. But fresh perspectives on the natural world are invaluable and help me see the value of our collections, and the beauty of the beasts, in fresh ways.

It’s lovely to see wasps in art; they obviously make good subjects, being generally beautiful, elegant and doing fantastically interesting things. But it’s also gratifying to see artists take inspiration from the organisation and philosophy of our collections as a whole. And to see that the idea of mutation and evolution is so compelling artistically as well as scientifically.

650081.jpg)