As a pioneer in the field of depicting symbiotic relationships, Maria Sibylla Merian is credited with inspiring such key entomological texts as De Nederlandsche Insecten (Sepp & Sepp, 1762) & British Entomology (Curtis, 1823-1840). Even today, her work is valued not just for its aesthetic appeal but also for the accuracy of its scientific content.

Born in Frankfurt am Main in 1647, Maria was the daughter of a Matthaeus Merian the Elder, a very well-known etcher, and Johanna Catharina Heim. After Matthaeus died in 1650, Johanna remarried. As a pupil of Georg Flegel (1566-1638), and a celebrated botanical artist in his own right, Maria’s stepfather Jacob Marrell (1614-1681) was to play a key part in the encouragement and development of Maria’s artistic talent. By the age of 11, Maria had learnt the art of copper engraving from her stepfather; by the age of 13 she was keeping a journal of her efforts rearing silkworms, including notes on metamorphosis. Both interests went on to shape her life.

Married at 18 years of age to the artist Johan Andreas Graff (1637-1701), Maria gave birth to her eldest daughter (Johanna Helena) in Frankfurt Am Main in 1668. After relocating in 1670 to Nuremburg, the couples’ second daughter (Dorothea Maria) was born in 1678.

_055714.jpg)

Before, between, and after the birth of her daughters Maria continued developing her artistic talents. Using her own preparations of paints and dyes on vellum, paper, and linen, Maria produced a number of still life works but also shared her knowledge by teaching local girls flower painting and embroidery. Indeed, Maria’s first published work Neues Blumenbuch (1675-1680) was issued in parts intended as a pattern book for such pursuits.

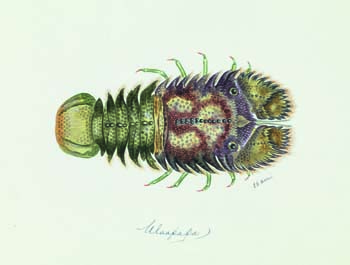

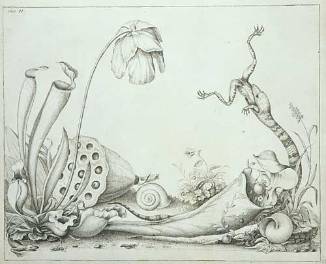

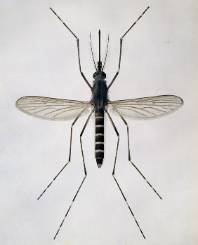

In 1679, the first part of Maria’s Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung was published. The work focused on insect metamorphosis, drawn from first-hand observations of life cycles and food plants, rather than drawings of dried specimens (as was usual at the time). Jan Goedaert (1617–1668) was known as a painter of insects (including their life cycle); Botanical artists such as Georg Flegel and Balthasar ven der Ast had included insects in their paintings. However, linking insects to the specific plants they lived and fed on was quite a new approach.

Referred to by Maria as her “caterpillar books”, Der Raupen also served to demonstrate Maria’s refinement of making counterproofs, or transfer prints. Most illustrations produced via the engraving process are a mirror image of the original illustration – Maria added an extra step to the process, pressing a fresh sheet of paper against the still-wet print from a copperplate. This removed any physical impression of the copperplate from the finished product, instead leaving an outline for the final painting. Radically for an author of the time, Merian often coloured the engravings herself.

A major change in Maria’s life came in 1681, with the death of her stepfather Jacob Marrell. Returning to her mother’s home in Frankfurt Am Main, Maria went on to publish a second part of Der Raupen in 1683, which was issued with an additional 50 plates and accompanying text.

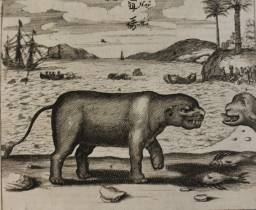

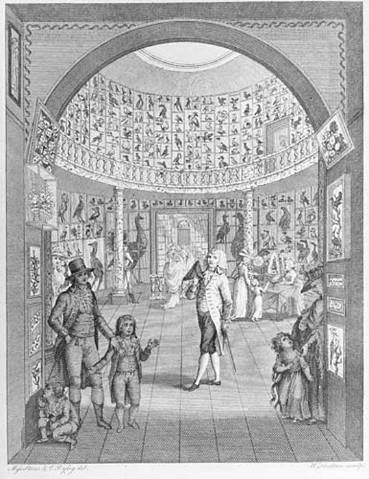

Maria’s life took another unexpected turn in 1685, when she entered the religious Labadist commune in Wieuwerd, Friesland, of which her brother Caspar was already a member. Her mother and daughters joined her in the move; her husband did not. Hosted in Castle Waltha, tropical insects and plants in the commune’s natural history collections caught Maria’s interest. Maria and her daughters moved to Amsterdam in 1691 after the deaths of her brother and mother (1686 and 1690 respectively). In their new home, all three became well known as natural history painters.

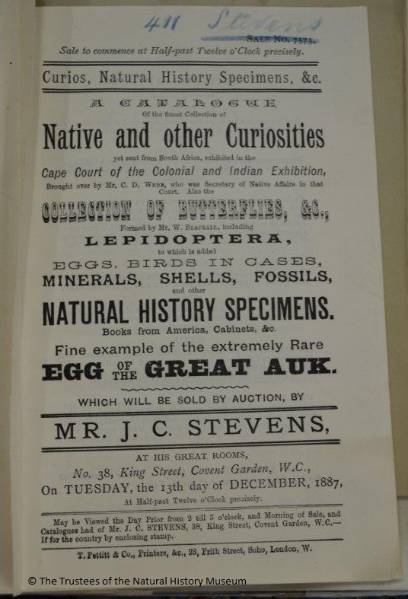

In 1699, Maria took the life-changing decision to travel to Surinam. Funded by selling off her artwork and natural history collections, Maria was accompanied by her daughter Dorothea rather than a male companion. Although Surinam was a Dutch territory at the time, for a woman to travel unescorted in this way was quite controversial. Maria made the concession of drafting her will, but proceeded with her journey nonetheless.

_026479.jpg)

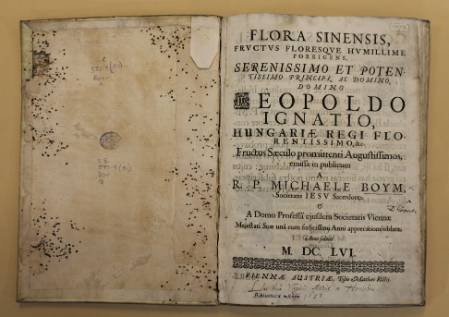

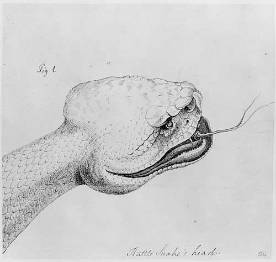

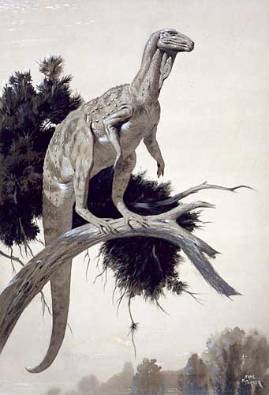

2 months of sailing later, Maria and Dorothea arrived in Surinam. Despite the ridicule of local Dutch sugar planters, the two women collected, reared, and painted the insects and plants of urban and jungle areas. After a serious illness (perhaps Yellow Fever), Maria returned to Amsterdam in 1701 with an extensive collection of plants, insects, and artwork. All three formed the basis of her highly acclaimed work Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, first published in Amsterdam in 1705. The publication in Latin and Dutch was funded in part by Maria’s commissioned art and engraving work.

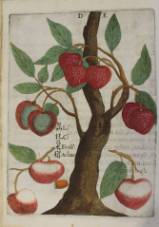

Many editions were coloured by Maria’s equally talented daughters, but although Metamorphosis used Maria’s original watercolours for all the illustrations, only three of the engravings made were her own. Many of the insects and plants depicted in the work were new or little known to scientists, with plants such as pineapples, prickly custard-apples, frangipani, pomegranates, bananas, watermelons, guavas, and cashews all making an appearance. Plants depicted were both wild and cultured, due to having been chosen for their relationship with the insects they hosted.

A good indicator of the esteem in which Maria’s work was held might be considered the 1711 purchase by James Petiver of some of her artwork, on behalf of Sir Hans Sloane, and the 1717 purchase of her original drawings by Czar Peter the Great. Later, although not impressed with the cost of her works, Carl Linnaeus still cited her illustrations for several plant species and over 100 animal species. Since that time, At least 6 plants, 9 butterflies, 2 bugs, 1 spider, and 1 lizard have named in Maria’s honour.

Unfortunately Maria suffered a stroke in 1715, and was unable to continue her work. In 1717, at the age of 70, she died in Amsterdam.

_026470.jpg)

Shortly after Maria’s death, a third volume of Der Raupen was published by her daughter Dorothea; this was followed in 1719 by the second edition of Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. The second edition of Metamorphosis was again published only in Latin and Dutch, but included 12 additional plates – 10 by Maria, 2 after the collections of Albert Seba. These plates provoked criticism by the scientific community due to some baffling inaccuracies – one plate suggested that American frogs metamorphosed into tadpoles, as opposed to European tadpoles growing into frogs! Criticisms of Maria’s work also stemmed from her emphasis on biology and observation rather than taxonomy. Although the Linnean system of binomial nomenclature that is used today wasn’t introduced until 1753, taxonomy and taxonomic names were still considered crucial to the scientific process.

In all, Metamorphosis appeared in 5 editions. The 3rd and 5th editions (The Hague, 1726 and Paris, 1771) appeared in Latin and French; the 4th edition (Amsterdam, 1730), was a translation in Dutch.

Although her interest was primarily in insects, Maria’s realistic and detailed paintings of the plants they live on have ensured her work is valuable is not just to art lovers, but also to scientific community.

Bibliography.

Harvey, J.H.V.

Maria Sibylla Merian: The Surinam album (commentary) (London: The Folio Society, 2006).

Magee, J.

Art of Nature: Three centuries of natural history art from around the world (London: Natural History Museum, 2009).

Ogilvie, M. & Harvey, J.

The biographical dictionary of women in science: Volume 2, L-Z (New York & London: Routledge, 2000). Pp.884-885

Pieters, F.F.J.M. & Winthagen, D.

Maria Sibylla Merian, naturalist and artist (1647-1717): a commemoration on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of her birth. Archives of natural history. (London: Society for the History of Natural History). Vol. 26, part 1 (February, 1999), pp.1-153

Stearn, W. T.

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) as a botanical artist. Taxon (Utrecht: International Bureau for Plant Taxonomy and Nomenclature). Vol. 31, part 3 (August 1982), pp. 529-534.

,+magnolia+warbler+NHMPL+015964.jpg)

_055714.jpg)

_026479.jpg)

_026470.jpg)