Linnaeus, sex and botany

Whilst the study of plants would appear a harmless scientific pursuit, during the late 18th century much controversy was caused due to the allusion to its sexual nature and the theory that plants, like animals, reproduced sexually. Although the sexual system of classification put forward by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1768) in his 1735 publication Systema Naturae was not the first to propose a sexual hypothesis in plants, he was the first to establish a complete system of classification on it.

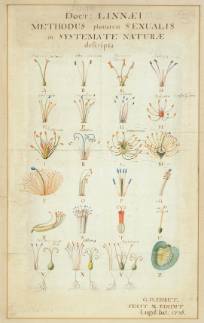

Above : The original drawing by Georg Ehret (1708-1780) to illustrate Linnaeus' sexual system. It was first published in Linnaeus' Genera Plantarum, first edition, 1737.

Linnaeus' theory was based upon counting the numbers of male and femlae reproductive organs inside the flowers. Descriptions such as "the calyx is the bride chamber in which the stamina and pistilla solemnize their nuptials" and analogies between humans and plants in statements such as "the filaments the spermatic vessels" and "the anthers the testes" served to highlight the reproductive floral parts of the plants.

The work was met with some resistance and by some deemed unnatural, in particular the German botanist Johann Georg Siegesbeck (1686-1755) who claimed it to be "repugnant and immoral". Smellie, in his chapter on The sexes of plants in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (p.653, 1771) wrote that "a man would not naturally expect to meet with disgusting strokes of obscenity in a system of botany" and that "men or philosophers can smile at the nonsense and absurdity of such obscene gibberish ; but it is easy to guess what effects it may have upon the young and thoughtless".

For others however such as Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), it inspired poetry :

This verse from the Love of Plants (Darwin, 1790) is the description of tumeric where "one male and one female inhabit this flower ; but there are besides four imperfect males, or filaments without anthers upon them, called by Linnaeus eunuchs".

Although many were shocked by the comparison with human sexuality, it was a very practical system of classifying plants and became accepted by renowned botanists including Nikolaus von Jacquin (1727-1817).

Linnaeus, Ehret and the frontispiece

The original illustration used to demonstrate Linnaeus' sexual system and published in the first edition of his Genera Plantarum in 1737 was drawn by Georg Ehret (1708-1770). Born in Heidelberg, Germany, Ehret's unique style and clarity of plant illustration was sought by specialists for the purposes of illustrating taxonomy and classification. This made him a perfect choice for Linnaeus as the scientific accuracy and precision of botanical illustrations are paramount in order to be able to distinguish the plants from other species and to enable correct identification. It also helped that Ehret considered himself and Linnaeus to be "the best of friends" and that when Linnaeus first showed him the new method of examining the stamens he understood it easily enough to produce the "tabella" (Ehret, 1894-5).

The drawing, completed by Ehret in 1736, shows the division of the vegetable world by Linnaeus into 24 classes. The 24th class were the cryptogams (plants without flowers) and in keeping with the male/female analogy were referred to by Linnaeus as "Clandestine marriage, Cryptogamia".

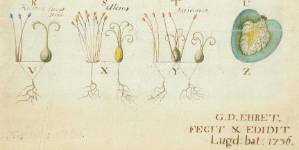

Above : The 24th class (the Cryptogams) indicated by the letter "Z" along with Ehret's name and the date of the drawing.

nb. The letters J and Y were omitted from this alphabetical arrangement to represent Linnaeus' 24 classes.

Whilst the brilliance of the colour remains after almost 300 years, the illustration is also interesting as on the verso there is the pencil outline of the drawing and when held up to the light is the exact image of the watercolour image on the front. The illustration therefore has been conserved and framed in such a way so it possible to see through the paper on both sides.

Above left : the completed watercolour image

Above right : the reverse image in graphite

References and further reading

Darwin, E. (1790-91) The botanic garden; a poem, in two parts : Part 1. Containing the economy of vegetation ; Part 2. The loves of the plants, with philosophical notes. J. Johnson : London. 2 vols.

Ehret, G. D. (1894-95) A memoir of Georg Dionysius Ehret. [Written by himself, and translated, with notes by E. S. Barton]. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 1894-95. pp.41-58

Fara, P. (2003) Sex, botany and empire : the story of Carl Linnaeus and Joseph Banks. Icon Books : Cambridge. 168 pp.

Jarvis, C. (2007) Order out of chaos : Linnaean plant names and their types. Linnean Society of London and Natural History Museum : London. 1016 pp.

Smellie, W. (1768-1771) Encyclopaedia Britannica : or, a dictionary of arts and sciences compiled upon a new plan &c. A. Bell and C. MacFarquhar : Edinburgh. 3 vols.

Stern, W. T. (2004) Botanical Latin. David & Charles : Devon. 546 pp.