I'm so tempted to say that a microfossil curator attends meetings and writes e-mails. Sometimes it feels like that. I decided to document a typical day back in January where e-mails and meetings helped prepare towards a loan for an art exhibition, gave news of a potentially exciting new acquisition and a possible research opportunity involving micro-CT scanning.

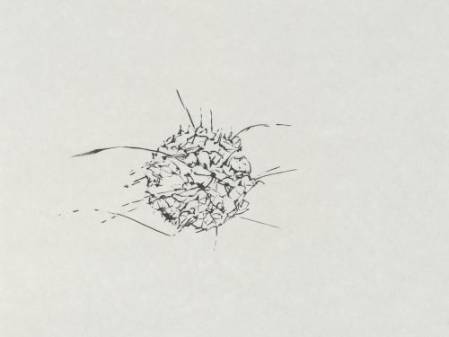

One of Irene Kopelman's items in the Gasworks Gallery based on microfossils from our collection

The bulk of the e-traffic involves preparations towards an exhibition that opened on 10 Feb at the Gasworks Gallery near the Oval Cricket Ground. Artist Irene Kopelman's work was partly inspired by some slides of radiolarian microfossils from our collections. We are preparing an exhibition loan of the slides and today there is a lot of correspondence discussing arrangements for two open day tours I am holding to accompany the exhibition.

Most microfossils are so small that I have to deal with images rather than the specimens themselves. We recently sent some specimens on loan to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington where a researcher has made some images for a publication and left them on an ftp site for me to collect. I am also making arrangements for other images of our specimens to be sent to us by one of our regular visitors. They have posted them on an excellent site for people interested in foraminiferal microfossils.

Aggerostramen rustica, a type of foraminiferal microfossil that builds a shell from sediment. In this case, sponge spicules have been chosen. This image has been posted on-line at the foraminifera.eu site mentioned above

Typically a day will not pass without some correspondence with future visitors to the collections and/or an actual visit from a scientist. Two visitors want to come in a couple of days time and another wants to visit the following week to discuss a short paper on a major collection of 2,500 slides that they donated last year.

In a few days time I'm off to our collections outstation in Wandsworth to meet OU PhD student Kate Salmon who is using our collections to study ocean acidification. I need to book a Museum vehicle to transport me to Wandsworth and to bring the collections back that she would like to borrow.

I mentioned meetings but you'll be glad to know that I'm not going to go into detail here. From one meeting I come away with two additional enquiries to answer; a request by a journalism student for a 5 minute mock radio interview and a student wants images of some of our specimens for their thesis.

I am also asked to assess a destructive sampling request as my boss is away. Sometimes our samples or specimens need further analysis to reveal their true scientific potential. In this case the borrower wants to make thin sections of fragments of fish fossils and to carry out 3-D imaging using a synchrotron (see my previous blog on sex in the Cretaceous for details of synchrotrons). The work will potentially give important details about early fish evolution so the request is ratified.

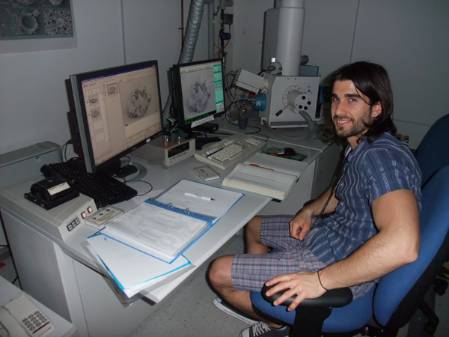

Erasmus student Angelo Mossoni using one of the scanning electron microscopes at the Museum.

The excellent research facilities here at the Museum offer many exciting possibilities. Today an e-mail has come in requesting bids for use of the micro-CT scanner. I want to test whether this method can provide 3-D images of some tiny specimens the reverse sides of which we cannot analyse at the moment because they are stored embedded in wax. If it works, some 3-D images of some of our most important specimens will be delivered to the web. Some of these species have been used extensively in studies on climate change and oceanography.

One message informs me that an exciting new sample has just been sent as a donation from Oman. When it arrives I will need to dissolve some of it in acid (vinegar) to release the tiny fossils. Traces of fish microfossil are clearly visible on the surface of the rock so this sounds very promising and possibly the subject of a new paper on early fish evolution.

It would appear from everything listed above that there is not much time for any other activities. However, documenting the collections for the web is one of our core duties so I find time in the afternoon to work towards a documentation project. I am also on duty for an hour to answer questions from my fellow curators and my mentee Jacqui about using the databasing system.

A number of people including my two new colleagues Tom and Steve, pop their heads round my door to ask questions about the collections or bring me information. Retired Museum Associate Richard Hodgkinson is in today and has some questions about his project. Another retired member of staff brings me a copy of his latest paper and former volunteer and now colleague Lyndsey Douglas comes to tell me that my blog has been quoted in the January edition of the Museums Journal!

It's an amazingly variable job being a microfossil curator and no day is ever the same as another. I love my job and I think of it as unique. I don't know of anyone else in the world who has a similar job in Micropalaeontology. If you have a similar job, I'd love to hear from you.