One of the most amazing things about working at the Museum is having access to world class facilities to support my work, whether that be managing the collections or doing research. Members of the Imaging and Analysis Centre have been analysing an important foraminiferal type specimen using the Museum nano-CT scanner. This produces a 3-D rendition of something less than half a millimetre wide and helps with classification of this important species that has potential to date rock formations, show past climates and ocean conditions.

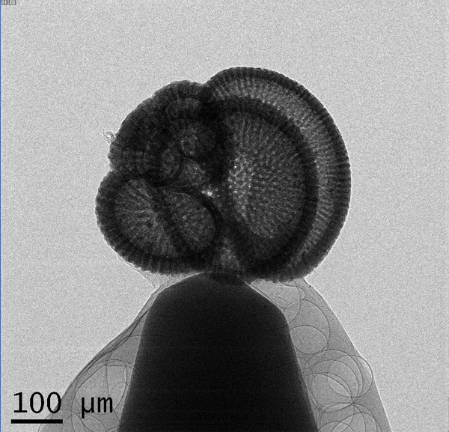

A prescan picture of one of the paratypes of the planktonic foraminifera, Globigerina prasaepis (Blow, 1969).

You can see the top of the mounting pin and the air bubbles in the adhesive I used. The scale bar is 0.1mm.

What's a nano-CT scanner?

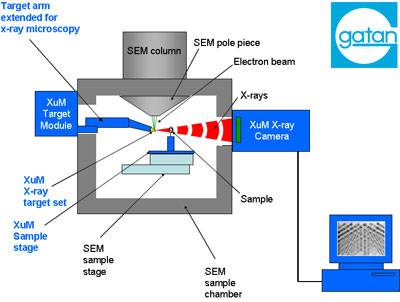

Electrons from a scanning electron microscope (SEM) beam are directed onto a metal target and this causes X-rays to be emitted. Tiny specimens or samples are then placed between the source and an X-ray camera, allowing 2-D projections like the one above to be taken. The diagram below is posted on the Museum web site where further details and specifications of the Museum nano-CT system can be found.

How is the specimen prepared for scanning?

The first thing to do is to mount the specimen on the head of a pin. To do this I used an adhesive called Paraloid B72 and a fine paint brush dipped in acetone. The specimen is then coated with a fine 20 nanometre coating of gold under vacuum in a sputter coater.

After this the pin needs to be placed precisely on a special holder or sample stage that is rotated through 360 degrees in the x-ray beam. An image is taken for each degree of rotation. The stage needs to be centred so that the specimen stays in the field of view while it rotates. Fortunately I had the expert help of Tomasz Goral to achieve this.

Tomasz is placing the specimen mounted on the end of a pin, onto the rotating sample stage.

Special software is used to take an image every 45 degrees while the stage rotates 360 degrees under the microscope seen above. This tells us where the centre of rotation of the stage is. The stage is then adjusted so that the specimen is as close as possible to its centre of rotation. With such a small specimen this is harder than you'd imagine but was done expertly by Tomasz.

The rotating stage with adjusting screws and the specimen on the end of a pin.

How long does it take?

Once the stage with the mounted specimen is placed into the SEM chamber there are still a lot of adjustments to be made. Different metal targets are available and, for our analysis, tungsten was chosen to produce the X-rays. Several test scans are required to make sure that the images produced are high enough quality to make 3-D reconstructions. Each image is produced by amalgamating a number of frames. The optimum number and length of frame needs to be chosen.

The final setting Tomasz chose was 20 frames of 12 seconds each for each degree of stage rotation. You can do the maths if you'd like to work out how long it took to take 360 of these images! Usually a scan would be done overnight and sometimes it can take as long as 24 hours.

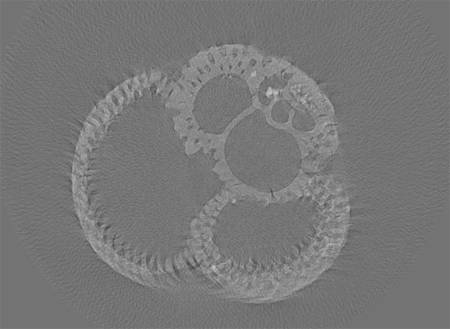

One of the slices produced by the Gatan software. You can see all the chambers inside the specimen

as well as the pores through the calcium carbonate wall of the specimen.

How do you get a 3-D image?

The X-ray projections for every one degree of rotation are then analysed using software developed by Gatan, the makers of the XuM camera. These projections were then overlaid to produce slices through the specimen that were further analysed using a programme called Drishti developed by the Vizlab at Australian National University. Dan Sykes of the Imaging and Analysis Centre used Drishti to produce a 3-D image of the foram that can be rotated, sectioned or studied at any angle or in any plane.

Film showing the 3-D rendition of the planktonic foraminifera, Globigerina prasaepis

Why are the results of interest?

Some members of the International Subcomission of Paleogene Stratigraphy are currently putting together an atlas of Oligocene planktonic foraminifera. The Oligocene spans a period roughly 24-33 million years ago. Subcomission member Dr Bridget Wade of the University of Leeds writes,

"The analysis of holotypes and original descriptions are key to determining and understanding taxonomic concepts of extinct planktonic foraminifera. Globigerina prasaepis was described by Walter Blow in 1969 from Tanzania. It has been a relatively under-utilised species, and the relationship to other taxa is yet to be fully determined."

2-D Scanning electron microscope images of this species show excellent preservation. However, nano-CT images like these allow us to produce a 3-D model and to look inside the specimen and view the arrangements of the chambers. Hopefully this will help to evalute its relationship to other species of planktonic foraminifera and help scientists to accurately identify this species in research samples.

Because planktonic foraminifera secrete their shells directly from ocean water, studies of the carbon and oxygen isotopic signatures of fossil specimens can tell us a great deal about the conditions in ancient oceans and about previous climates. The distribution of various fossil and recent species can also tell us about the positions and directions of oceanographic currents.

Some examples from our collection of scale models of exceptionally preserved ostracods produced from CT scans.

The real specimens are about 1mm long. For details of how the scans were made, see my post on sex in the Cretaceous.

The future

The Museum is committed to making details of its collections available electronically via the web so they can be used for teaching or in research projects like those mentioned above. The scans produced can also be manipulated using special software to produce various 3-D models and 2-D cross sections. Scale models of these specimens can be printed in acrylic using special 3-D printers (see examples above) and could be made available to interested parties.

The raw data set can be made available to anyone interested in studying any species scanned. This method could be particularly useful for studying species of Foraminifera that are usually illustrated and identified in thin section. Making thin sections of microfossils is a dying art so virtual sectioning using this technique has real potential as it is non-destructive and the plane of section can be varied by choice. Previously we had to rely on the skill of the thin section maker to cut the microscopic specimens exactly through the centre.

The images I have shown are promising but there are some interference patterns that make the final rendition slightly fuzzy (see the slice above for example). The Museum have recently purchased and installed a new scanning electron microscope to replace the one that helped towards creating these trial CT-scans. It will be interesting to work with Dr Farah Ahmed and the CT scanning team in the Imaging and Analysis Centre to see if the new microscope can produce even better results.

I am greatly inspired by the British Geological Survey who are producing 3-D images of their type collections as well as those from other UK museums. It would be great to work with them and do a similar project on microfossil type specimens like the one presented here.