So it is 6:14 on a Monday morning - though, for me, it was really an hour earlier still because I am heading into Hamburg, Germany, to record for the final episode of the BBC Radio 4 series 'Who's the Pest?'. I am tired; the problem for me with getting up early is that - paradoxically - I don't sleep well due to worrying that I will oversleep.

So I had some coffee ... but I was sure that none of that had to do with the general slightly crazy mood I was in. Instead I am sure that it had everything to do with the prospect of being suspended from the ceiling by technology that mimics fly feet! And it is to that end, that I am sitting on a very smooth and quiet train, looking out at the snow, and heading to meet Professor Stanislav Gorb, the inventor of the most amazing pieces of biomimicry.

Biomimicry is the study and application of biological organisms and adapting their effects for our own uses. We see a lot of natural mimics - to appear more dangerous to predators than they actually are, hoverflies use protective mimicry to look like bees and wasps, while spiders mimic ants to enable them predate on them (aggressive mimicry).

As a species we have long been interested in mimicry and have been trying to copy the natural world for our own benefit for thousands of years. We study and adapt insect gait in our robots (oh how we can learn from the mighty cockroach for this); we mimic the pheromones of moths to lure pests to traps and we copy their egg-laying abilities to make better hypodermic needles (needles that are so small as to not cause any reaction and ones that can actually bend out of the way of objects so as not to damage any of our vital organs) - all very funky stuff.

Protective mimicry in action (taken from wikipedia): 'Two wasp species and four imperfect and palatable mimics. (A) Dolichovespula media; (B) Polistes spec.; (C) Eupeodes spec.; (D) Syrphus spec; (E) Helophilus pendulus; (F) Clytus arietes (all species European).

Of note, species C–F have no clear resemblance to any wasp species [THIS IS WHAT WIKI SAYS!]. The three hoverfly species differ in the shape of their wings and body, length of antennae, flight behaviour, and striping pattern from European wasps. One fly species (E) even has longitudinal stripes, which wasps typically don't. The harmless wasp beetle does not normally display wings, and its legs do not resemble those of any wasps.'

... But, right now, I want to talk about why I had been suspended from a ceiling in Germany like a one-armed orang-utan.

So we were ushered into a very high-ceilinged office and introduced to Stanislav and made to feel welcome. Gorb has three main interests when it comes to insects: plant-animal interactions; functional morphology and biomechanics; and biological attachment. It is this final area of research we will concentrate on today.

We have been using adhesives for an awfully long time. Archaeologists have discovered pots that have been held together by sap that are 4,000 years old. Scotch tape, as it is known comercially, was invented by Richard Drew in 1930 and we have been relying on it - and its relatives - ever since. But eventually it ceases to work; the glue dries out or it rots away, leaving a residue when you unpeel it from the binding surface.

Stanislav has been pondering these very problems for over 10 years - but through an entomologist’s insight. And a novel solution came from a slightly sensitive situation that a male beetle often finds himself in. Examine this photograph of some very down-and-dirty beetle porn.

Steamy beetle action

© nutmeg66/flickr

I once worked on the heather beetle, Lochmaea suturalis, at the then Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, ITE, (now the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, CEH) in Dorset. It was an amazing time and I had quite a collection of beetle porn (although I was more fascinated when a beetle was parasitised by the Tachinid fly, Medina collaris, and I used to spend my lunch times eating sandwiches and watching maggots crawling out of their bums only for them to decide to crawl back in again ...).

What a beautiful fly... Medina collaris

Used with permission, © Hakon Haraldseide

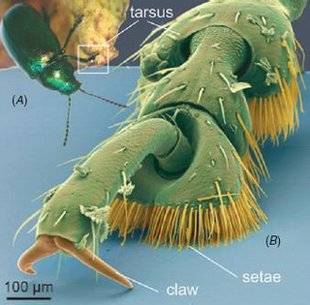

I digress … throughout the mating process, the male beetles have to cling on with utter tenacity while the female carries on her daily business. Not much will put a woman off her food … even in this situation! So how does he mange to do this? We know of many animals that have an amazing ability to climb up walls, with geckos being the obvious ones. But Stanislav looked at what was happening on the beetles' feet (or tarsal segments) as they are known.

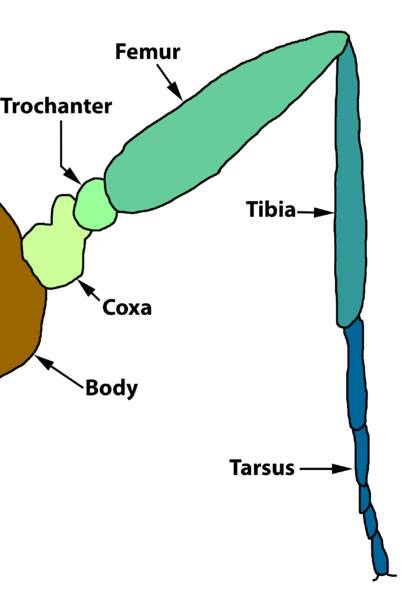

Here is a leg of a beetle:

Now, their tarsal segments can be hairy – really, really hairy.

This is an image from one of Stanislav's papers on the subject. Check out the mass of setae (the hair-like projections).

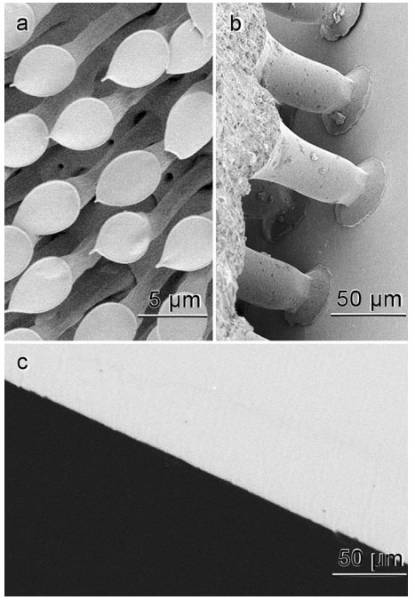

At the end of the setae are structures that range in shape from spatula shapes to mushrooms. So from the naturally occurring shapes Gorb, with the help of a development company, constructed some synthetic tape (called PVS in the image below). Here is a lovely piece on him explaining how the tape works.

(a) Scanning electron micrographs showing the mushroom-shaped setae in an attachment pad of a male beetle, Gastrophysa viridula, (b) biologically inspired mushroom-shaped microstructured PVS sample, (c) and the surface of the control PVS sample.

So now we have the tape ... how does this relate to me? Well this is how, with very little dignity, I am able to dangle from the ceiling - much to the amusement of everyone else in the room:

First time up, I fell off the ceiling! But this was because there was a screw loose, so the tape did not bind evenly. With the screw sorted, I was back up there again, holding onto a handle attached to a piece of tape that had just been shoved on to the suspended glass square. One-handed! Nearly wrenched my socket out but amazingly the tape held.

Just for the amusement of my producer I then repeated this several more times so she could record the right level of grunting! It’s not all glamour you know! However, it was amazing to see the application of taking a really small natural structure and using it for our benefit. We can use this tape for many different things, including mechanised arms that move around very delicate and clean surfaces such as those of mobile phones. No more smudges. And what is also fantastic about this tape is that it can be reused! Marvellous.

And I now have a small piece and am amusing myself in my flat sticking various objects to the wall ...