Max Barclay, collections manager for Coleoptera and Hitoshi Takano, leader of the Coleoptera section's Africa expeditions including extensive exploration of Tanzania and Zambia, tell us about a very exciting find for us... Dr. Livingstone's beetles...

Livingstone on the Zambezi

David Livingstone returned to England a national hero in 1856 after becoming the first man to undertake a trans-continental journey from the port of Luanda on the Atlantic Coast of Angola to Quelimane in Mozambique where the Zambezi River meets the Indian Ocean. He published a book of his travels in 1857 titled Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa selling a remarkable 70,000 copies making him a very wealthy man. With the huge amount of public support behind him, he persuaded Lord Clarendon, the Foreign Secretary and Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister to finance an expedition to the Zambezi River to open it up as an ‘economic highway’ to allow cotton and sugar to be grown in large quantities on the floodplains of this river. Livingstone abhorred slavery and had hoped that it could be banished through legitimate commerce.

Dr David Livingstone at Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park

On the 10th March 1858, Livingstone set sail from Liverpool docks with his team which consisted of his brother Charles, naturalist and medical doctor John Kirk, geologist Richard Thornton (who came with a glowing recommendation by President of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Roderick Murchison), artist and storekeeper Thomas Baines RA and engineer George Rae.

Within only a few months of arrival, the expedition was doomed. On his earlier voyage down the Zambezi, Livingstone was told about, but did not investigate, a set of rapids known as Cahora Bassa (in modern day Mozambique). This set of rapids made it impossible for any vessel to sail up the river even at full flood at the end of the rains. Despite this disappointment, he navigated a tributary of the Zambezi, the Shire River, and became the first Westerner to accurately document Lake Malawi.

The expedition was eventually recalled from London as the results could not justify the cost.

The major positives to come out of the expedition were the scientific specimens and observations made by Livingstone and his team.

Hitoshi on the banks of the Zambezi at Ngonye Falls

The natural history specimens

There were large quantities of natural history specimens (plants, birds, mammals and reptiles) collected on this expedition. In the years following the return of the expedition (1864-1865), many lists and new species were published in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Heinrich Dohrn published on the mussels, George Robert Gray & John Edward Gray on birds/mammals/reptiles, Albert Gunther on reptiles/fish and Kirk on mammals (and birds in the journal IBIS). Many of these specimens are in the NHM.

It is interesting that there were no lists of insects published from this expedition despite the fact that in the very same year (1864), the insects collected by Captain John Hanning Speke on his pioneering trip to the Great Lakes of Africa were published by Frederick Smith of the BMNH.

Livingstone himself writes in the introduction of his book 'Narrative of and expedition to the Zambesi and its tributaries' (1865) on p.11 that "the collections, being government property, have been forwarded to the British Museum and to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew; and, should Dr. Kirk undertake their description, three or four years will be required for the purpose."

But where did the beetles go?

150 years after the 2nd Zambezi Expedition, two beetle specimens were known.

Goliathus kirkianus Gray, 1864; Holotype BMNH 1864-10

This small number is remarkable when one considers that Livingstone’s was a major, government funded expedition at the height of the age of exploration and collecting. For comparison, Alfred Russel Wallace, during eight years in the Malay Archipelago (1854-1862), almost single-handedly collected more than 83,200 beetles, that is over 10,000 a year, and it is hard to spend a day in the collections without finding more of his material. Of course Wallace was not government funded, and collected at least in part in order to pay his expenses by selling his specimens through Stevens’ Auctions in London, a major Natural History auction house that was patronised by the collectors (and indeed the museums) of the world.

If we look at the two ‘known’ Livingstone specimens, the first, difficult to overlook because of its huge size and striking pattern, is a Goliath Beetle described as a new species in 1864 by G. R. Gray who states “Dr. Kirk has, on his return from the Zambesi, added to our knowledge a species of the genus Goliathus, which he obtained as long ago as November 1858 when he picked it up among the hills of Kebrabassa”. Kebrabassa is the same as Cahora Bassa, the site of the rapids that were to doom the whole expedition, and Kirk evidently stumbled across the beetle during the first year of the trip, and dutifully traipsed it around Africa for more than half a decade, bringing it to Gray soon after his return along with a motley collection of other curios. He was rewarded by a very swift description and a name in his honour; perhaps it was all a bit too swift, because Goliathus kirkianus was soon synonymised with the widespread Goliathus albosignatus Boheman, 1857, which had trumped it for priority by 7 years. The Holotype remains in the collection of the NHM, and bears the registration number ‘1864-10’. It was hoped that by following up this registration number in the immaculately written massive, longhand leather-bound registers held in the library, that we could learn more about what else came back from the expedition, but the register entry for ‘1864-10’ (‘presented by Dr. Kirk and collected by himself’) lists only 16 specimens – a motley selection of 11 leaf beetles (‘Cassida’ and ‘Haltica’), a hermit crab with a shell, a locust, an assassin bug, and two caterpillars in spirits! It doesn’t even mention the goliath beetle. It seems that Gray, perhaps in his haste and excitement at finding such a gem in a mixed bag of African oddments, skimped on the paperwork and failed to list the specimen. Of course, this raises the question of what else might have been put in the collection without being properly listed, and may still be lurking there. The registers are much easier to search through than 22,000 drawers of almost 10 million beetles.

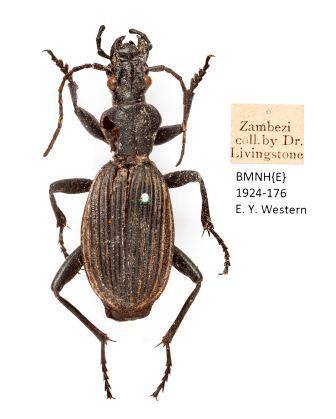

This brings us to the second specimen, a common flower chafer Marmylida impressa, found by Hitoshi Takano in a drawer full of the same, common, species but distinguished by a small typewritten label next to it saying ‘specimen collected by Dr. Livingstone’. This label was apparently provided by a curator, probably former scarab curator Mick Bacchus in the 1960s or 1970s, to draw attention to the specimen’s interesting provenance. The specimen itself is labelled ‘Zambezi, Coll. By Dr. Livingstone’ and has a registration number ‘1924-176 E. Y. Western’. Western was a private collector, whose collection of some 10,000 unsorted beetles was presented to the Museum by his daughter after his death in 1924.

Marmylida impressa (Goldfuss), 1805

That was the end of the story until, in 2014, curator Max Barclay was doing a routine inspection of some old boxes of unincorporated material. Every museum has unincorporated accessions, though in recent years we been systematically sorting, recurating, databasing and incorporating ours into the main collections, where the specimens are safe from pests and available to the world scientific community. After many years of concerted efforts in this direction, we are getting to the bottom of the barrel where old unincorporated accessions are concerned, and most of what is still in loose boxes has been picked over and judged to be of little interest by successive generations of curators. One particular box was identified as a priority for incorporation - not because it was ostensibly special material - it was 19th century specimens of common beetles with poor data and in relatively poor condition - but the box had warped and split, and posed an unacceptable risk to its contents.

The original E.Y. Western store box in much need of curatorial care

While recurating the material a decapitated histerid beetle of the giant species Pactolinus gigas caught Max’s attention, initially because it needed to be repaired - until he noticed the label ‘Zambezi, Coll. By Dr. Livingstone’, identical to the one on the Marmylida flower chafer found in the main collection by Hitoshi. Looking at the side of the box Max saw the initials ‘EYW’ and realised that these few last dusty boxes were the remaining few residues of the 10,000 specimen collection donated by E. Y. Western, the rest of which had been incorporated in the 90 years since the collector’s death. Western was the same collector who had provided the Marmylida. Hastily Max went through the remaining half dozen boxes and found spread among them a total of 14 specimens of 9 species and three families, all labelled in exactly the same way. All were common African species.

Beetles from E.Y. Western's store box of beetles collected by Livingstone

Western’s collection in 1924 would have consisted of hundreds of boxes, and for nearly a century, most of the curators employed on the beetle section would have extracted, accession-labelled, and incorporated whatever they considered to be of interest. The Elateridae would have been processed by Christine von Hayek, the scarabs by Mick Bacchus, tenebrionids by Martin Brendell, melyrids and dermestids by Enid Peacock, staphylinids by Peter Hammond, chrysomelids by Sharon Shute, weevils by Sir Guy Marshall and Richard Thompson, water beetles by Balfour-Browne, coccinellids by Bob Pope - the gaps in the boxes read like a roll-call (maybe a rogue’s gallery) of curators and researchers of the past. What is left, by extension, is what was not considered to be of much interest by anyone, though it is apparent that they were all looking at it from a taxonomic rather than a historical point of view. In those days the modern curatorial practice of taking a box and emptying it, in order to reduce the number of boxes and systematically complete recuration and incorporation one collection after another, and then making a record of what you did, was not established. Therefore, it seems likely that the 14 specimens remaining in the boxes were but a fraction of the Livingstone material possessed by Western. It was not held as a separate collection, but placed taxonomically across his series, so it seems likely that the vast majority of it has already been incorporated, but the logistics of searching for individual specimens in a whole collection without knowing what species they belong to makes looking for a needle in a haystack seem a matter of routine. We did experiment with picking common species likely to occur in Zambezi and then searching through the main series, and this revealed 4 specimens of the very common flower chafer Diplognatha gagates, but so far nothing else has been traced. Systematic databasing of the collection will no doubt eventually reveal everything, but this is a slow process and has only just begun.

Max Barclay with the Livingstone beetles in the Waterhouse building of the Natural History Museum

So, the interesting question is, how did Edward Young Western (1837-1924), a lawyer based in Craven Hill, Bayswater, come to have Livingstone collected materials, especially considering Livingstone’s belief that the specimens were ‘government property’? The most parsimonious explanation is that another member of the expedition had fewer scruples, or less financial security than Livingstone, and specimens were sold. The registers show the Natural History Museum in 1862 purchased 9 Zambezi specimens at Steven’s Auctions from ‘Dr. Livingstone’s exhibition [sic]’. This is interesting because in 1862 Livingstone was still in Africa- it could be that someone was sending material back to Stevens for sale without the boss’s knowledge. There may have been other lots where the Museum did not bid, or was outbid, and possibly these, or some of these, were bought by Western for his private collection.

Of course, if well looked-after, the life-span of an insect specimen is many times the life-span of a collector, so private collections like E.Y. Western’s usually come to museums, like rivers and streams ultimately flow into the sea. The clearing of accessions and unincorporated material, as well as widespread databasing and digitising of material in the collections, will no doubt continue to throw up surprises and treasures for years to come. Livingstone explored with maps, a bible and a gun, and a medicine chest, but today some of the last frontiers for exploration are the great Natural History Collections themselves. How much of Dr. Livingstone’s material remains to be discovered in such collections, we can only presume.

There has been some press coverage on the discovery of Livingstone’s beetles, including a brief BBC Radio 4 ‘Today Programme’ interview with Max Barclay

The story was covered on the Natural History Museum’s website

Other press coverage includes

The Independent, 20.09.14, Pg 32

Culture24

The Times of India

The Livingstone specimens were first shown to the public at ‘Science Uncovered’ on 26th September by Hitoshi Takano, and are now available to view in ‘Dinosaur Way’ in the Public Galleries of the Natural History Museum, for a limited time only.

Termophilum alternatum Bates, 1878

blog.jpg)